WASHINGTON — Since Donald Trump left office in January 2021, the former president has not fared well at the Supreme Court, despite its conservative majority, including three justices he appointed.

When Trump tried to prevent prosecutors from obtaining his financial records, the court rejected his request.

When Trump attempted to stop a congressional committee from accessing White House documents from his administration, the court rebuffed him.

When Trump asked for a special master to review classified documents seized from his Mar-a-Lago residence, the court turned him away.

When Trump sought to stop his tax returns being disclosed to House Democrats, the court refused to intervene.

The court’s rejection of Trump in those cases showed that the justices had “remarkably little interest in intervening in any of the cases about former President Trump’s personal behavior,” said Steve Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

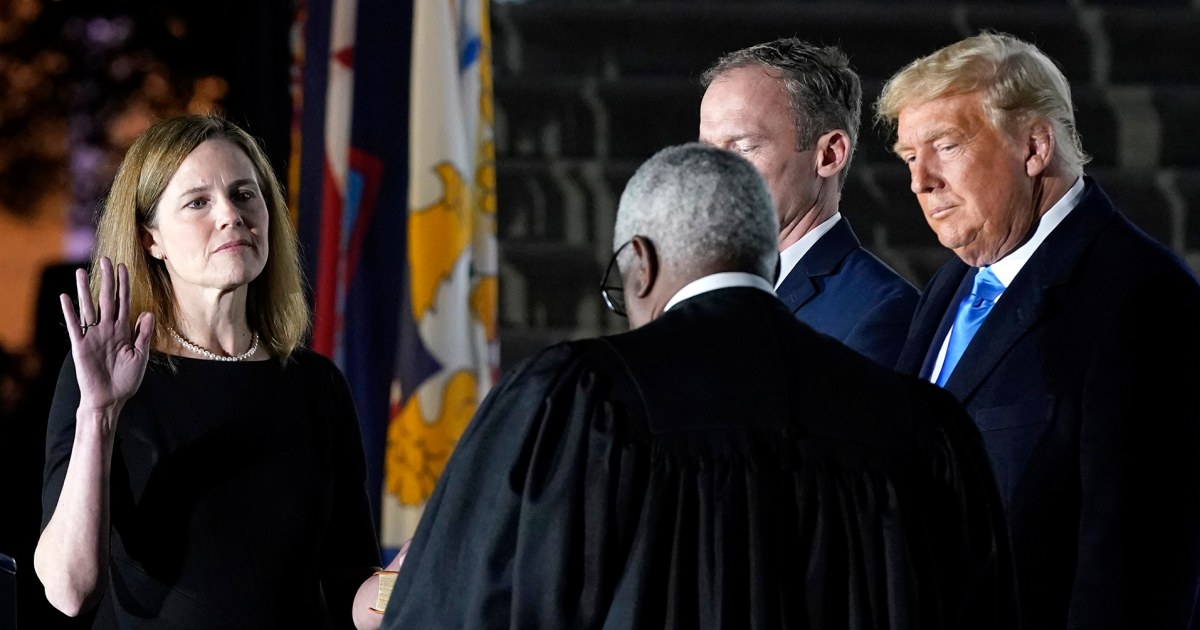

These losses illustrate how, even as major new legal issues involving Trump reach the justices, he does not always receive a warm reception at the court he helped shape with his appointments of Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, ensuring a 6-3 conservative majority.

While all three Trump appointees have delivered for the conservative legal movement that helped put them on Trump’s radar as possible candidates, most notably in the court’s ruling in 2022 overturning the landmark abortion rights ruling Roe v. Wade, they have not been so amenable when it comes to Trump himself.

The court also turned away all of the cases in 2020 seeking to challenge the presidential election and, even when Trump was president, his administration had a mixed record.

While the court upheld his travel ban on mostly Muslim-majority countries, it rejected his efforts to unwind the Obama-era program that protects young immigrants often known as “dreamers” from deportation and his administration’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the census.

In fact, at times Trump has railed against the justices, including in November 2022 when the court allowed members of Congress to access his tax returns.

“Why would anybody be surprised that the Supreme Court has ruled against me, they always do!” he wrote in a Truth Social post.

“The Supreme Court has lost its honor, prestige, and standing, & has become nothing more than a political body, with our Country paying the price,” he added.

The court is likely to weigh in on two important legal questions in the next few months: Whether Trump can be deemed ineligible to run for office over his role leading up to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and whether he has immunity from being prosecuted for that conduct because he was president at the time.

Most recently, Trump did successfully persuade the court last month not to take up special counsel Jack Smith’s attempt to fast-track a decision on whether the former president is immune from prosecution.

Trump welcomed that as a victory, although the issue could still return to the court in short order, with an appeals court hearing arguments next week. The Supreme Court will likely have a big say in whether a trial can occur before the election.

Legal experts point out that both the immunity and the eligibility issues are significant and untested legal questions that might merit the Supreme Court’s intervention, unlike some of Trump’s earlier requests.

The justices themselves “understand well, even if Mr. Trump does not, that their role is to interpret the law, not to protect any particular public figure’s personal interests,” said Richard Garnett, a professor at Notre Dame Law School. Any critics who suggest otherwise are “badly mistaken,” he added.

But even when assessing those cases, it might be difficult for the court to separate Trump the person from the legal issues, said Aziz Huq, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School.

“They’re real legal issues, but neither of these cases would exist in the absence of the unique pattern of behavior that the former president has engaged in,” he said.

“It’s not like the court’s going to decide either of those issues in some sort of vacuum,” Huq added.