Environment

/

March 13, 2024

Geologists may have voted down formal recognition of the Anthropocene as a geological epoch, but we still need to act to prevent ecological crisis.

A view of the glaciers as polar bears, one of the species most affected by climate change, walk in Svalbard and Jan Mayen, on July 15, 2023.

(Photo by Sebnem Coskun / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

“Welcome to the Anthropocene,” The Economist declared in 2011, referring to a proposed new unit of geological time. The term was intended to describe how the impacts of homo sapiens on the planet have become so significant a force within nature that they deserve the designation of a new geological epoch. We have perhaps been as transformative of the earth as other forces—from the movements of plate tectonics to plants’ conquest of land—that produced the grand transformations of the deep history of our world.

The Economist’s cover story was perhaps the first major public outing for the concept, which atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and the late biologist Eugene Stoermer introduced in 2000. The term has since spread throughout the humanities and popular culture, prompting a library’s worth of books, commentary, articles, podcasts, and even a death-metal album.

The word is bandied about as if geologists, and stratigraphers in particular, had already formally altered the geological time scale (GTS) to include the new epoch.

But they hadn’t.

Formalization of the term would require an alteration to the GTS, a representation of the history of the earth perhaps as scientifically important to geoscientists as the periodic table is to chemists. This is no minor undertaking, and so in 2009 the Anthropocene Working Group, a committee of geologists, ecologists, paleontologists, stratigraphers, and other earth science experts was formed to formally consider whether there was substantial scientific evidence to warrant a change to the GTS. A decade later, after much consideration, the Working Group proposed a start date for the epoch in the 1950s. This is when industrial production, construction of large dams, use of agricultural chemicals, transportation, electrification, and emission of greenhouse gases, among other human activities, accelerated. Separate from the working group, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program has called this “lift-off” of humanity the “Great Acceleration.” In particular, the working group was tasked with identifying potential stratigraphic markers—clear changes within rock layers—that identified the beginning of the proposed epoch. The Great Acceleration also coincides with the first atomic weapons tests that produced a thin layer of radioactive debris within sediments around the world—the very clear stratigraphic marker that the working group was looking for.

Current Issue

But last week, the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, the body at the International Union of Geological Sciences responsible for any changes to the GTS within the current geological period, rejected that proposal by a large margin. (“Period” meaning the level within the hierarchy of deep time above the level of “epoch” but below the level of “era.”) Some from the minority are contesting the vote, but most believe that a reconsideration is extremely unlikely. After 15 years of deliberation, it appears to be case closed.

So does this mean we were premature in using the word Anthropocene? Do we have to stop using the term? Is everything all right with the planet after all?

Very much no.

Climate change is far from the only aspect of human impact that the Anthropocene was intended to encompass, but it’s a key one, and so conservative climate skeptics are now certain to hay about the supposed “fiction” that is the Anthropocene. But we still need to act.

Erle Ellis is an ecologist who investigates global change. He resigned from the working group last year because he felt that the concept was too narrowly constrained. Humans have been radically transforming the planet for tens of thousands of years, he argues, so to restrict the geological conception of this to the 1950s misunderstands the evolutionary and ecological novelty of people, and as a result risks contradiction in our political and ethical response to it.

Many of the ecological phenomena of concern, such as mass extinction, radical transformation of ecosystems, and even aspects of climate change push back well into the Holocene epoch and even beyond, long before the 1950s or the Industrial Revolution—the start date originally proposed by Crutzen, or even the 15th-century origin of the Columbian Exchange, that interchange of plants, animals, diseases, and technology between the New and Old Worlds after Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Lead pollution from mining began 2,000–3,000 years ago. Human-produced greenhouse gas emissions of sufficient volume to produce atmospheric effects began 7,000–8,000 years ago, as a result of the spread of farming. The Late Quaternary mass extinction of megafauna (the extirpation of some 65 percent of large animal species) began some 132,000 years ago as humans spread across the world out of Africa.

Ellis supports the vote against recognition of the Anthropocene as a geological epoch. Instead, he wants us to conceive of it as a geological event.

“The Anthropocene is still a geologically relevant term,” he told The Nation, “but as a geological event along the lines of the Great Oxygenation Event.”

Ellis is referring here to the advent of the first organism to photosynthesize, cyanobacteria, and thus produce great volumes of oxygen gas—oxygenating the atmosphere. This event occurred from roughly 2.4–2.1 billion years ago, in turn causing the first mass extinction event, for until that point, oxygen was toxic to life.

“The Great Oxygenation Event is also not recognized in the geological time scale,” he said. Yet scientists use this non-epochal term on a regular basis, and it plainly was one of the most geologically and biologically transformative developments in the history of the planet.

He notes that evidence of the scale of human-caused ecological impacts have only grown over the last 15 years. In that time, for example, we have learned that we do not merely need to rapidly reduce our greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid dangerous global warming but to eliminate them entirely.

“Nothing has really changed by this no vote. A yes vote would have changed things, but only for scientists using the term ‘Anthropocene Epoch’ publishing in journals,” he continued. “Every other setting…would have remained the same.”

“Keep calm and carry on,” he added. “It’s still the Anthropocene.”

The analogy to the Great Oxygenation Event reminds us that the earth is always, constantly changing, and thus ecological change is not in itself bad. The event, sometimes referred to as the Oxygen Holocaust, was Janus-faced. Geochemists estimate that at the end of the process, there had been an over 80 percent reduction in the size of the biosphere. But the more complex life that followed would not have been possible without this ecological revolution, for it has vast energetic requirements that only metabolism of free oxygen can service. It was life destroying, but also life giving.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

So the anthropocene event is another episode, like the oxygenation event, that changes the course of evolution. Humans’ incredible capacity for cultural evolution and thus technological change is a novelty within evolution every bit as radical as photosynthesis. But as there is no purpose or direction to evolution, this is not something that can be said to “harm the planet.” The decision thus signals that we should reconceptualize humanity’s relationship to the rest of nature as an organism within nature rather than as something external to it, perverting a “balance of nature” that does not exist.

The Anthropocene is however something that, if we are unable to decouple its benefits from its damages, very much threatens us humans.

And while humans have always been radically transforming the earth, it remains the case that since the 1950s, the scale of our transformation has markedly sped up. The term “Great Acceleration” remains a very useful descriptor that also sits outside the geologic time scale, but still recognizes the very real intensification of earth-system transformation identified by the Anthropocene Working Group.

All of this raises a key issue for progressives: The Great Acceleration’s impact on the earth coincides with the postwar welfare state and the industrial policy and institutionalization of trade unions that produced the western middle class. Thus the Great Acceleration is not really anthropic but social-democratic (in its very broadest sense of reduction in inequality and some level of economic planning).

But upon discovery of environmental problems such as climate change, such social-democratic planning is also much more nimble than the profit incentive is at decoupling human development from negative environmental impacts. Each of the five countries with the fastest declines in the carbon intensity of energy performed this act via public-sector-led clean energy transition, for example. Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is a recognition, if an imperfect one, that markets left to their own devices cannot solve climate change. Thus the optimal solution to the ecological challenges produced by social democracy is, ironically, also social democratic: more planning, more IRA, more Green New Deal.

The failure of the Anthropocene to be formally recognized as an epoch, the analogy of the current moment to the Great Oxygenation Event, and the continued utility of the Great Acceleration as a geological concept but outside the GTS thus remind us that we should be thinking about how the profit incentive undermines our ability to correct environmental problems in a timely fashion. It is this that we should emphasize rather than thinking that humanity is an interloper in nature, a scourge on the planet.

Recent developments also remind us that we don’t need the imprimatur of geology to be able to recognize that human actions are undermining ecosystem services. Even without a formal geological epoch designation, we already know, and all too well, that the problems we face here are unprecedented in our species’ history.

Don’t let the climate skeptics lead us to believe any differently: We still need to act.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It takes a dedicated team to publish timely, deeply researched pieces like this one. For over 150 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and democracy. Today, in a time of media austerity, articles like the one you just read are vital ways to speak truth to power and cover issues that are often overlooked by the mainstream media.

This month, we are calling on those who value us to support our Spring Fundraising Campaign and make the work we do possible. The Nation is not beholden to advertisers or corporate owners—we answer only to you, our readers.

Can you help us reach our $20,000 goal this month? Donate today to ensure we can continue to publish journalism on the most important issues of the day, from climate change and abortion access to the Supreme Court and the peace movement. The Nation can help you make sense of this moment, and much more.

Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

More from The Nation

There may never be another Flaco, but there will be other birds in the city to love. May we take better care of them.

Joan Walsh

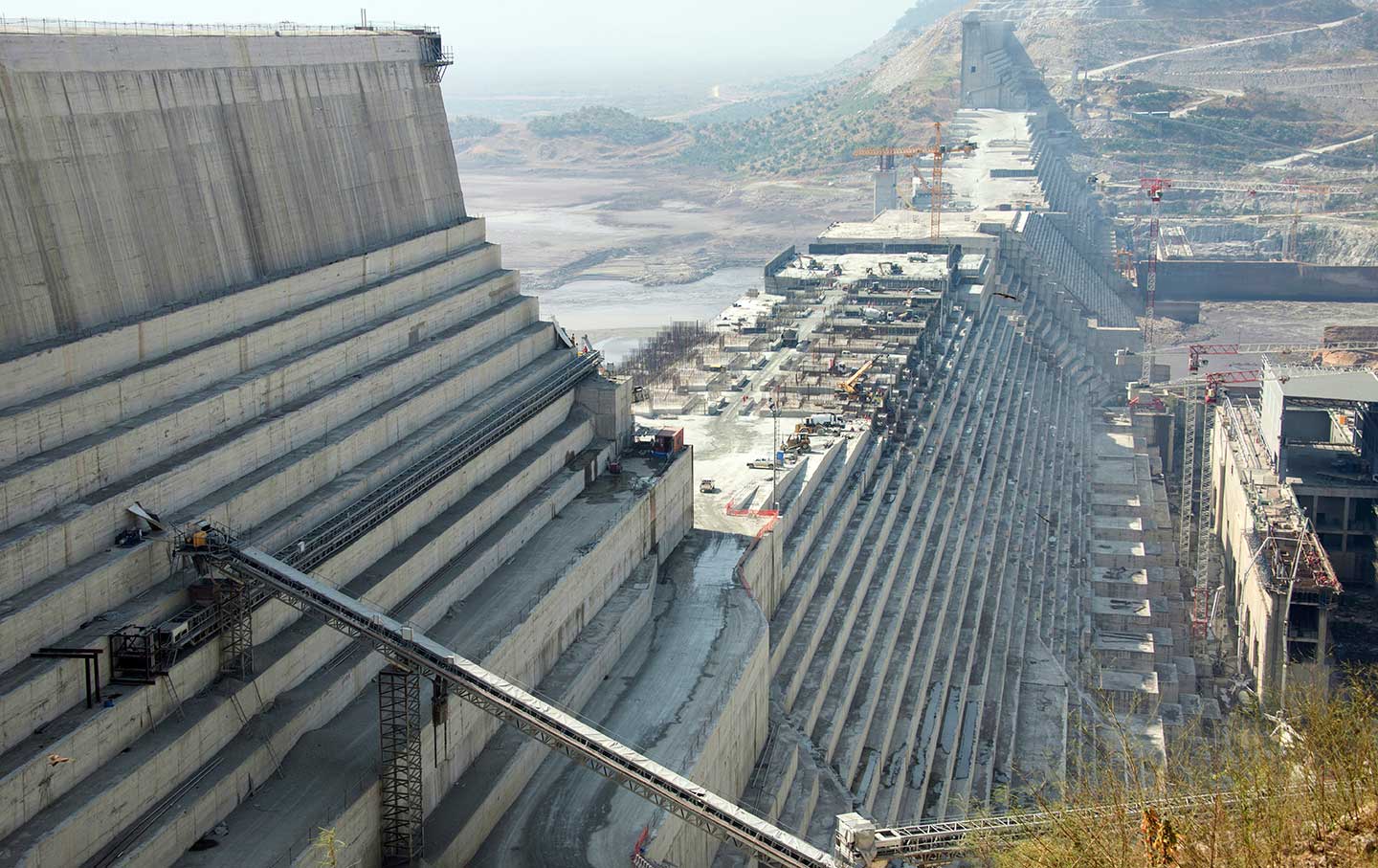

The dispute over Ethiopia’s enormous dam should be a warning of what the future holds on a hotter, drier planet.

Joshua Frank

Northern Virginia is grappling with the environmental effects of a booming data-center empire.

Ella Fanger

At the Cleantech North America conference, the fates of climate-tech start-ups are tangled into the balance sheets of companies who caused the crisis in the first place.

Molly Taft