Could the union victory at an electric bus manufacturing plant in Alabama turn the South into a hub for quality jobs in the green economy?

Workers at the New Flyer factory in Anniston, Alabama, celebrate their new union.

(Courtesy IUE/CWA)

Organized labor is in the midst of a fierce campaign to make inroads at auto manufacturers in the South, most recently at the Mercedes plant in Vance, Alabama, where on May 17, 56% of workers voted narrowly against joining the United Auto Workers. But a few months before the unsuccessful vote at Mercedes, workers 100 miles away at an EV bus manufacturing plant in Anniston, Alabama, unionized and won a historic contract. In January 2024, the majority of the around 600 workers at a plant run since 2013 by New Flyer, the largest transit bus manufacturer in North America, signed a union card to join the International Union of Electrical Workers-Communications Workers of America (IUE-CWA). Over the last couple of years, workers at the company’s other plants in Kentucky and New York have unionized, joining two longtime union shops in Minnesota. Together, they now make up the largest union in the public transit bus manufacturing sector in the United States, with over 2,350 members.

Current Issue

While Southern states have chipped away at protections for workers for decades, New Flyer workers like Shannon Franks remember that union jobs have long provided well-paying, high-quality jobs to the region. Her dad left the mountain town of Ider, Alabama, population 700, to find work, and landed in Chattanooga, where he got a union job with the Tennessee Valley Authority that paid for him to attend electrical school. “They gave him a chance,” she told me. Now, Franks works at the Anniston plant installing motors in the backs of electric buses. When she and her co-workers won their union at New Flyer, “It was like history repeating itself,” she said.

Just six months after the organizing drive officially began in November 2023, New Flyer workers ratified a historic contract with significant pay raises, restrictions on forced overtime, and expanded vacation time. “The wage package alone is life-changing for me,” said New Flyer employee Ryan Masters. “Now I’ll be able to save up some vacation time and spend more time with family for those pivotal moments.”

The rapid road to contract ratification was made possible by a years-long campaign by CWA and a coalition of community groups including Jobs to Move America (JMA), a nonprofit policy center founded in 2013 that works to ensure that the jobs created by government-funded transit projects are high-quality and serve marginalized communities. In 2022, New Flyer signed an agreement with the coalition to provide training opportunities and hiring pathways for workers from historically disadvantaged groups. The company also agreed to voluntarily recognize unions that formed at its plants, meaning that New Flyer workers weren’t subjected to union-busting tactics like captive-audience meetings during their recent organizing drive, unlike workers at the nearby Mercedes plant.

Workers at Mercedes in Vance and New Flyer in Anniston are part of a growing electric vehicle industry across the South, where roughly 40% of the U.S.’ electric vehicle manufacturing jobs and investment dollars are concentrated. Much of the Biden administration’s historic investments in green energy tech have flowed to the South, where companies like New Flyer build zero-emission buses for cities like New York, Boston, and Los Angeles that are electrifying their public transit systems.

New Flyer workers hope their victory will boost organizing across the South by workers building the cars and buses that will power the green transition. “This is for all of us,” said Franks. “It’s huge for the state of Alabama.” Erica Iheme, Co-Executive Director of JMA, said the agreement with New Flyer helps set the standard for companies in the public transit and green manufacturing sectors to provide high-quality, well-paying jobs. “We want to meet this moment to make sure that labor standards and good jobs are attached to this new type of work.”

Masters didn’t want to sign a union card, at first. Growing up in Alabama, he had always heard that unions were “greedy.” But after a couple of weeks of talking to organizers and his pro-union co-workers, “I figured out that a union is not an outside organization,” he said. “It’s just a coalition of the workers sticking together.” Once he decided to support the campaign, Masters became an active organizer himself, answering his co-workers’ questions about the union. “That’s how I was able to get educated,” he told me. “By talking to organizers and finding out.” He told them what he heard that made him change his mind. “The union is a sense of community in my mind. It’s a lot of brothers and sisters together, helping one another.”

The campaign at the Anniston plant was also supported by other New Flyer workers at the company’s facilities 16 hours away in Minnesota, which have been unionized for over 20 years. Matt LeLou, president of the union local that covers the two Minnesota plants and a welder at New Flyer for over two decades, said it was a “no-brainer” for him to travel to Anniston to talk to workers. “The union has made such a huge difference for people in our plant,” he told me. “Especially when you’re well-organized and can mobilize at contract time.” One of the main fears LeLou heard was that “the union was going to come in and just dictate to the membership this is how it’s going to be,” he said. “And that’s not how it is. The membership is the highest authority in our plants up here.”

On January 31, 2024, the union enlisted a local pastor to tally the authorization cards, who verified that the majority of the plant’s around 600 employees supported unionization. Because New Flyer had previously signed a neutrality agreement with CWA, the union was automatically recognized by the company. Masters and other members of the bargaining committee met with New Flyer representatives and secured a tentative agreement for a new contract in just two and a half months. On May 16, workers ratified the contract overwhelmingly, with 99.39% voting in favor of the agreement which will increase wages by up to 38% by 2026 and guarantee cost-of-living adjustments. The contract also restricts forced overtime, expands vacation, paid time off, and parental leave, and adds Juneteenth as a paid holiday.

“I never thought I would find another competitive paying job at my age,” said Marcus King, a 50-year-old electrical technician who started at New Flyer after the nearby Goodyear tire plant where he had worked for nearly three decades shuttered in 2020. At Goodyear, he was a member of the United Steelworkers, and he drew on that experience to represent his coworkers on the bargaining committee. “We build the same buses they build at the other plants,” he said. “We felt that we should be compensated, financially and otherwise, just the same as those other plants.”

The organizing didn’t end once the contract was ratified. Alabama is a right-to-work state, so workers have to opt-in to becoming dues-paying members. King and other worker organizers have now gotten a strong majority of their coworkers to sign up for the union. “I just had to explain to them the wins that we had in that contract,” said King. “That’s when they came around.” Masters is looking forward to starting regular union meetings and building up their local. “It feels like I have a new purpose at work,” he said.

Masters has been at New Flyer long enough to remember the last attempt at unionization, in 2015, which he opposed after the company held mandatory meetings to share anti-union messaging. This time around, the company pledged to voluntarily recognize the union and remain neutral during the campaign, refraining from union-busting tactics like captive audience meetings. That neutrality pledge was the result of a multi-year campaign by CWA, JMA, and other community groups targeting the public agencies that buy New Flyer’s buses in the more labor-friendly cities of New York and Los Angeles to get the company to sign an agreement to provide high-quality jobs to workers from disadvantaged groups and support worker’s right to organize.

Over the last decade, as city agencies have transitioned their public transportation fleets to green technology, JMA has pushed for high workplace standards in transit manufacturing. JMA developed a policy tool called the U.S. Employment Plan, which allows companies to commit to uphold certain standards for working conditions and community engagement as they bid for city government contracts.

In 2013, New Flyer won a $508 million contract from the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority to provide up to 900 buses and signed onto a U.S. Employment Plan pledging to provide more than 50 jobs above a certain pay rate at its facility in Ontario, CAIn the following years, based on conversations with workers and reviewing pay stubs from New Flyer’s facilities, JMA grew concerned that the company wasn’t upholding their commitments from the agreement. New Flyer had pledged to pay workers at least $18.35 an hour, but the documents reviewed by JMA indicated workers were making $17 or less when they started at the facility. In 2019, the organization filed a fraud complaint against New Flyer alleging that it was misrepresenting the value of the wages and benefits it promised to provide to workers as a condition of receiving local funds.

At the same time, a coalition of community groups in Alabama including JMA, CWA and other unions, faith groups, and environmental groups, launched a public campaign to highlight the effect of low pay and discriminatory working conditions on New Flyer workers. The coalition publicized a study by researchers at Alabama A&M University that found a pay gap between Black and white workers at New Flyer’s Anniston plant, and that Black workers were more likely to be denied promotions and get injured at work. Coalition members attended the American Public Transportation Association conference to raise awareness about the study and distributed an open letter from anonymous Black workers describing racist treatment at New Flyer. Employees also testified before local transit boards that were considering granting contracts to New Flyer about the impact New Flyer’s low wages and benefits had on them and their communities.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

At the time, New Flyer spokesperson Lindy Norris told In These Times that the company disputed the claims in the public letter and that JMA had been waging “a very public, aggressive and antagonistic attack on [New Flyer America].” She added, “We take any and all allegations of racism, sexism, toxic workforce culture, and pay inequity seriously, and have investigated singular and atypical incidents following multiple allegations made by JMA.”

In 2022, New Flyer settled the LA Metro lawsuit for $7 million while denying any wrongdoing and signed a community benefits agreement with JMA covering its plants in Alabama and California (New Flyer’s operations in California are now mostly dormant). A year after the agreement was signed, JMA’s Southern Director Will Tucker wrote that the agreement was “having a noticeable impact” at the company,” including through a new system for discrimination complaints, enhanced safety training, and hiring pipelines for workers from historically disadvantaged communities. “The partnership with New Flyer gave us, as Southern workers, hope that we can create not only quality products and build out this infrastructure but also we can do it in a space of good jobs and collaboration,” said JMA’s Iheme.

The company also penned a neutrality agreement with CWA pledging to voluntarily recognize unions that formed at all of its plants. IUE-CWA President Carl Kennebrew said the union’s partnership with JMA was “crucial” and that their policy tools and campaign strategy led to New Flyer maintaining neutrality. “Reaching this milestone at New Flyer has been a testament to the power of collaboration and the unwavering determination of our workers,” he said in a statement. Leading up to the recent union win at its plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Volkswagen had also agreed to remain neutral, though its response to organizing was less consistently “high-road” than New Flyer’s. The UAW filed unfair labor complaints against Volkswagen for retaliating against worker organizers.

Organizers at the Anniston plant see their win as part of a broader movement to bring high-paying, good-quality jobs in the green economy to the South, even as Alabama is now trying to discourage other neutrality agreements. On May 31, Governor Ivey signed a law that will prevent companies that voluntarily recognize unions from receiving economic incentives from the state. For now at New Flyer, “I feel like I made history here at this plant,” said King. “Hopefully this will bring really great jobs in the future.” Kennebrewsaid that the New Flyer campaign is a key part of the union’s vision for a just transition. “This initiative not only supports environmental sustainability but also ensures that these new jobs are good union jobs, providing stability and a promising future for American workers and the communities where they live.”

Masters hopes the fight at New Flyer will help end the “Southern discount” on labor costs. “I’m tired of being paid less than somebody who lives six hours from me,” he said. According to U.S. Census data, Alabama’s autoworkers earned almost $16,000 less than their counterparts in Michigan in 2019. The Alabama victory will increase New Flyer workers’ bargaining power across the country, including at its plants in Minnesota, Kentucky, and New York, said LeLou, by preventing a race to the bottom for wages and benefits.

Because of the training programs New Flyer agreed to create in the new contract, Franks will be able to become an electrician, just like her dad. “When I told him that they’re going to have an electrical apprenticeship program and I’m top of the list to go, it just made it full circle,” she said. “It’s something that he’s proud of and he’s so excited for me to learn it and I am too. If it wasn’t for the union, I wouldn’t have that opportunity.”

More from The Nation

“There are lines that cannot be crossed,” said a member of the board of California’s Public Employees Retirement System.

Left Coast

/

Sasha Abramsky

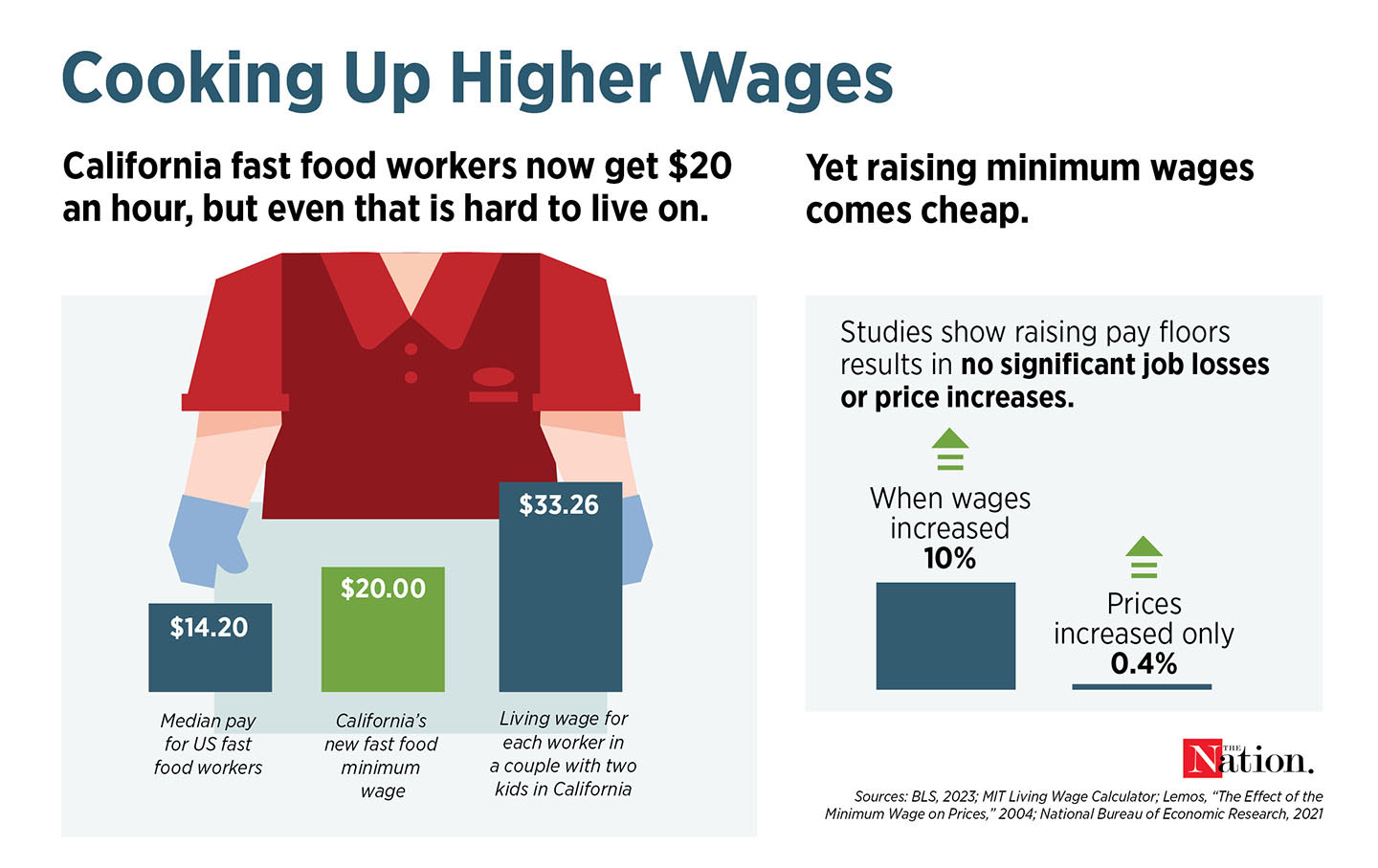

Studies overwhelmingly show that the effect of increasing the minimum wage on employment rates is basically zero.

The Score

/

Bryce Covert

Matt Stoller and Stacy Mitchell discuss the battle against monopoly power.

Q&A

/

Laura Flanders

Exclusive: An independent review of Amazon’s annual safety report finds that the company’s warehouse workers experience a disproportionate share of injuries.

Ella Fanger

July 1, 2024 The Win for EV Workers in the South You Didn’t Hear About Will California’s new farmworker labor law survive this assault by the not-so-wonderful Wonderful Company? Da…

David Bacon

The problem is systemic: Freelance life is underpaid. The solution must be systemic too.

Amy Littlefield