I have almost a half-century of memories of this place, which taught me everything from optical illusions to orbital mechanics

Article content

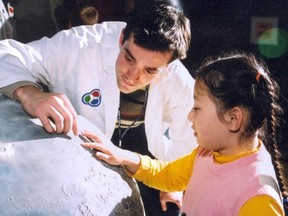

The Ontario Science Centre opened on Sept. 26, 1969. It was a Friday. I was just shy of eight weeks old. So you can forgive my young self for later thinking it had been built expressly for me. Just a short bus ride away from my home in Scarborough, the Science Centre was a teacher, sometimes a babysitter and, in a weird way, even a friend.

Sure, school taught me the nuts and bolts of chemistry, physics, math. But the Science Centre delivered the wonder. It started with that incredible building, designed by renowned architect Raymond Moriyama, who died just last year, aged 93.

Advertisement 2

Article content

The style was mostly Brutalist — think lots of thick concrete — but it was unexpectedly airy as well, with vast rooms and high ceilings. A long pedestrian bridge, once decked in royal blue carpeting, provided awesome views down into the Don Valley. Three escalators featured piped-in bird calls and the real thing outside the windows, reminding visitors that here was a rare human-made structure that insinuated rather than imposed itself on the landscape, exiting within the environment, not atop it. It was an odd, wondrous philosophical theme for a site dedicated to the power of science.

And oh, the science it held. On the upper levels, the halls of Earth, Space and the Molecule. A huge map of the world would spring into three dimensions to show relative rainfall in different locations. A tongue-in-cheek video examined all the weird chemical additives in modern food. You could stand in a booth that would “freeze” your shadow on the wall; drink chemically pure water; and watch as a laser burned through a piece of wood.

Those long escalators led to even more themed halls. Canadian Resources, featuring tiny models of a St. Lawrence Seaway lock and the Far North community of Inuvik. Transportation, where you could test your driving reaction times, watch a model hydrofoil lift out of the water, and learn about the Canadian-made Mosquito combat aircraft. Communication, flanked by a pair of parabolic dishes that would carry a whisper to someone on the other end of the room.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

Recommended from Editorial

-

Ten chicks a-hatching: science museum’s penguin baby boom

-

Ontario Science Centre abruptly closed due to structural issues

Then there was the Science Arcade — half classroom, half playground. This is where you’d find bicycle-powered radios and lights, soundproof chambers housing theremin, drums and synthesizers, and a lopsided room that made you appear to grow to ridiculous heights as you moved through it.

I recall fine-tuning my motor skills there by tracing a star shape while looking at it in a mirror, and learning how to estimate the passage of precisely 60 seconds. (I’m still pretty good at it.)

Tiny theatres dotted the Science Centre, offering up all manner of incredible facts. IBM’s “Mathematics Peepshow” introduced topology, symmetry and the power of doubling. (Place a grain of wheat on the first square of a chessboard, two on the second, four on the third, then eight, 16, 32 and so on, and you’ll eventually have enough wheat to stretch to the star Alpha Centauri and back, several times.)

The film Powers of Ten unlocked the relative sizes of things in the universe, from the structure of the atom to that of the galaxies. Clay or The Origin of Species wasn’t really science, but it featured fun claymation backed by a groovy jazz quartet. Not everything has to teach you something.

Advertisement 4

Article content

But the Science Centre did teach. This one building was where I discovered the Doppler effect, orbital mechanics, optical illusions, chaos theory, water filtration, genetics, fractals, biofeedback, harmonic resonance, papermaking, relative frames of motion, logic gates, holography, electroplating, rubber manufacturing, digital data preservation (BBC’s Domesday Project, not to mention CDs) fibre optics, spectroscopy, multiplexing, cosmic background radiation, and an early chatbot named ELIZA, circa 1985. You would type something and she’d say a variation of “Tell me more!”

Many of these memories stem from the Science Centre’s early days, and not all the exhibits were there at the end. But I enjoyed many of the changes over the years, and brought my own kids to explore the OMNIMAX theatre offerings, KidSpark, the lush rainforest, the tunnel of silence (what a treat for a parent!), the paper-airplane wind tunnel, cutting-edge materials, and the human biology hall. Temporary exhibits over the years included a Star Trek show, MythBusters, the science of weather, and a display of retro video games that clearly influenced my eldest child, whose room is now stuffed with them.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Things change. But if you’d told me, during one of my many visits to the Science Centre during the 1980s, that it would abruptly close in the mid-2020s, I’d have nodded and asked if it was due to fallout from the atomic wars. And if you’d then said no, it was because of potential roof collapse from heavy snowfall — on the first full day of summer no less — I’d have scoffed and called you crazy. I mean, I’m no engineer, but I have spent many an hour in the Hall of Engineering. Find a way to fix this iconic location, for the love of science. Keep it there, so future generations can explore the grounds, the building, and the knowledge within. Maybe build a subway line out to it?

Also, a city like Toronto without a science centre? Might as well tell me the planetarium was going to shut down too. (It did, in 1995. And while the shell of it remains on Queen’s Park, weathered and peeling, there are no immediate plans to revive it. The Science Centre is slated to be resurrected at Ontario Place, but no earlier than 2028.)

The Ontario Science Centre closed on June 21, 2024. It was a Friday. I was just shy of 55 years old. So you can forgive my old self for thinking it had been done expressly to me. Just a short drive away from my home in Toronto, the Science Centre was a teacher, sometimes a babysitter and, in a weird way, even a friend. And I didn’t even get a chance to say a proper goodbye.

Article content