Willie Mays, the electrifying “Say Hey Kid” whose singular combination of talent, drive and exuberance made him one of baseball’s greatest and most beloved players, has died. He was 93.

Mays’ family and the San Francisco Giants jointly announced Tuesday night he had died earlier in the afternoon.

“My father has passed away peacefully and among loved ones,” son Michael Mays said in a statement released by the club. “I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood.”

The center fielder was baseball’s oldest living Hall of Famer. His signature basket catch and his dashes around the bases with his cap flying off personified the joy of the game. His over-the shoulder catch of a long drive in the 1954 World Series is baseball’s most celebrated defensive feat.

Mays died two days before a game between the Giants and St. Louis Cardinals to honor the Negro Leagues at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama.

“All of Major League Baseball is in mourning today as we are gathered at the very ballpark where a career and a legacy like no other began,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said. “Willie Mays took his all-around brilliance from the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League to the historic Giants franchise. From coast to coast in New York and San Francisco, Willie inspired generations of players and fans as the game grew and truly earned its place as our National Pastime. … His incredible achievements and statistics do not begin to describe the awe that came with watching Willie Mays dominate the game in every way imaginable. We will never forget this true Giant on and off the field.”

Few were so blessed with each of the five essential qualities for a superstar — hitting for average, hitting for power, speed, fielding and throwing. Fewer so joyously exerted those qualities — whether launching home runs; dashing around the bases, loose-fitting cap flying off his head; or chasing down fly balls in center field and finishing the job with his trademark basket catch.

“When I played ball, I tried to make sure everybody enjoyed what I was doing,” Mays told NPR in 2010. “I made the clubhouse guy fit me a cap that when I ran, the wind gets up in the bottom and it flies right off. People love that kind of stuff.”

Over 22 MLB seasons, virtually all with the New York/San Francisco Giants, Mays batted .302, hit 660 home runs, totaled 3,283 hits, scored more than 2,000 runs and won 12 Gold Gloves. He was Rookie of the Year in 1951, twice was named the Most Valuable Player and finished in the top 10 for the MVP 10 other times. His lightning sprint and over-the-shoulder grab of an apparent extra base hit in the 1954 World Series remains the most celebrated defensive play in baseball history.

He was voted into the Hall in 1979, his first year of eligibility, and in 1999 followed only Babe Ruth on The Sporting News’ list of the game’s top stars. (Statistician Bill James ranked him third, behind Ruth and Honus Wagner). The Giants retired his uniform number, 24, and set their AT&T Park in San Francisco on Willie Mays Plaza.

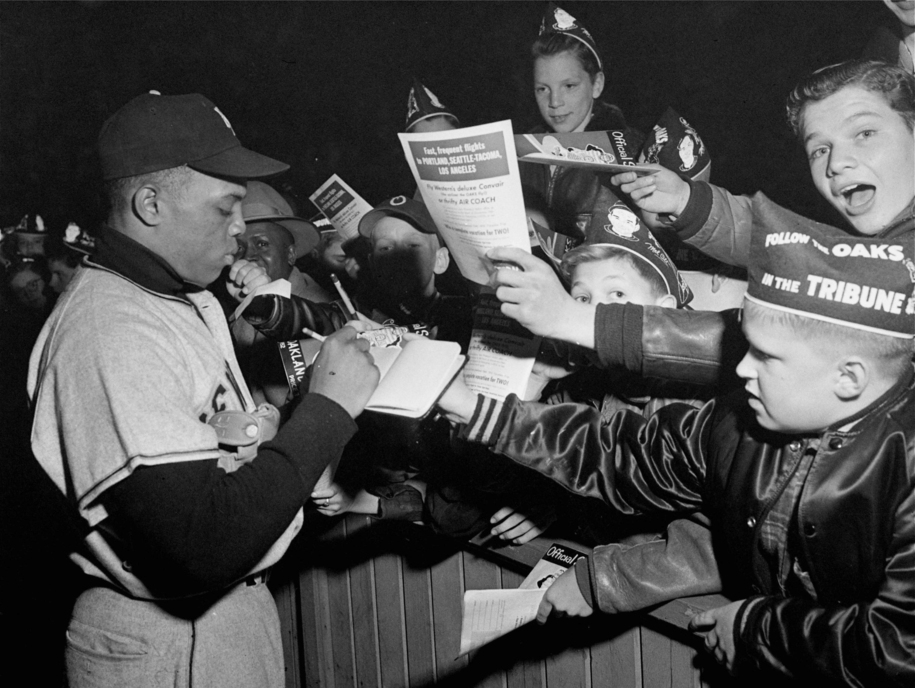

For millions in the 1950s and ’60s and after, the smiling ball player with the friendly, high-pitched voice was a signature athlete and showman during an era when baseball was still the signature pastime. Awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2015, Mays left his fans with countless memories. But a single feat served to capture his magic — one so untoppable it was simply called “The Catch.”

In Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, the then-New York Giants hosted the Cleveland Indians, who had won 111 games in the regular season and were strong favorites in the postseason. The score was 2-2 in the top of the eighth inning. Cleveland’s Vic Wertz faced reliever Don Liddle with none out, Larry Doby on second and Al Rosen on first.

With the count 1-2, Wertz smashed a fastball to deep center field. In an average park, with an average center fielder, Wertz would have homered, or at least had an easy triple. But the center field wall in the eccentrically shaped Polo Grounds was more than 450 feet away. And there was nothing close to average about the skills of Willie Mays.

Decades of taped replays have not diminished the astonishment of watching Mays race toward the wall, his back to home plate; reach out his glove and haul in the drive. What followed was also extraordinary: Mays managed to turn around while still moving forward, heave the ball to the infield and prevent Doby from scoring even as Mays spun to the ground. Mays himself would proudly point out that “the throw” was as important as “the catch.”

“Soon as it got hit, I knew I’d catch the ball,” Mays told biographer James S. Hirsch, whose book came out in 2010.

“All the time I’m running back, I’m thinking, ‘Willie, you’ve got to get this ball back to the infield.’”

Mays was Rookie of the Year in 1951, twice was named the Most Valuable Player and finished in the top 10 for the MVP 10 other times.