There is no trial date in the classified documents case against former President Donald Trump, and none in sight.

Instead of steering the case as quickly as possible to a jury, the judge, Aileen Cannon, has burned day after day of court time listening to lawyers haggle over defense motions that make what experts say are long-shot arguments to dismiss charges, exclude evidence or otherwise attack the prosecution.

On Friday, the latest chapter in this legal saga will unfold in Cannon’s courtroom in Fort Pierce, Florida, when she is set to preside over a daylong hearing on the question of whether special counsel Jack Smith’s appointment was proper under the Constitution — an argument similar to one that was rejected by other judges when applied to special counsels Robert Mueller, who ran the investigation of Trump’s relationship with Russia, and David Weiss, who is prosecuting Hunter Biden.

On Monday, Cannon is slated to hear a defense challenge of how Smith’s office has been funded, another line of argument that has been uniformly rejected by other courts. And on Tuesday, she will consider the question of whether a D.C. judge erred by allowing testimony from Trump’s lawyer under the crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege.

Those are the sorts of motions, some criminal law experts say, that few judges would have entertained during lengthy hearings. Instead, they say, she could have read the legal briefs and issued a ruling.

By continuing to require hours of court time for nearly every matter of dispute, Cannon, a Trump appointee, has played right into Trump’s strategy of trying to delay a trial in this case until after the election. While she says she is merely trying to ensure fairness, her actions have raised questions among legal scholars.

“Motions that other judges would decide routinely and quickly, Judge Cannon puts them on her docket and delays for an inordinate amount of time,” said Joyce Vance, an MSNBC legal contributor and a former U.S. attorney. “It’s like death by a thousand cuts.”

Most peculiar, experts say, is Cannon’s decision to allow outside parties to argue before her Friday that Smith’s appointment is unconstitutional.

“It’s highly unusual to bring in amicus,” John Fishwick, a former U.S. attorney, said using part of the Latin term for “friends of the court.” “That never happens.”

Shira Scheindlin, now retired after 22 years as a federal judge in New York City, added, “There’s no reason to let (outside parties) come in and argue their brief. They don’t have a right to be heard.”

It may be appropriate, she said, to allow Trump’s lawyers to argue briefly about the issue of Smith’s appointment, because there is a unique issue — he is the only special counsel in recent memory who was never confirmed by the Senate. Those challenging his appointment say the founders did not envision investing such power in someone never confirmed.

In general, however, Scheindlin believes that Cannon has mishandled the classified documents case by failing to move expeditiously.

“She drags out everything … she’s very slow and she’s expanding the time that it takes and now she’s got motions piled up, they’re all backlogged.”

Cannon’s defenders vehemently dispute this view. Jon Sale, a former federal prosecutor in Florida who recommended Cannon for the judgeship, said the criticism of her judicial approach is motivated mainly by disagreement with some of her rulings.

“For the life of me, I don’t understand why she’s criticized for holding hearings in a case that is extraordinarily important, that the whole world is watching,” he said. “It shows she’s giving careful thought to it. If you take politics out of this, there should be no rush to judgment.”

Cannon did not respond to a voicemail request for comment left in her chambers.

Appointed by Trump in 2020, Cannon has been on the federal bench for less than four years and this is, by far, the highest-profile matter she has handled.

Born in Cali, Colombia, she earned an undergraduate degree from Duke University in 2003 and graduated magna cum laude from the University of Michigan Law School in 2007.

After clerking for a judge and working at a law firm, she served from 2013 to 2020 as an assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of Florida, working in major crimes and in the appellate section.

A member of the conservative Federalist Society, she has long been a Republican, but not politically active. She has said her mother fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba at age 7.

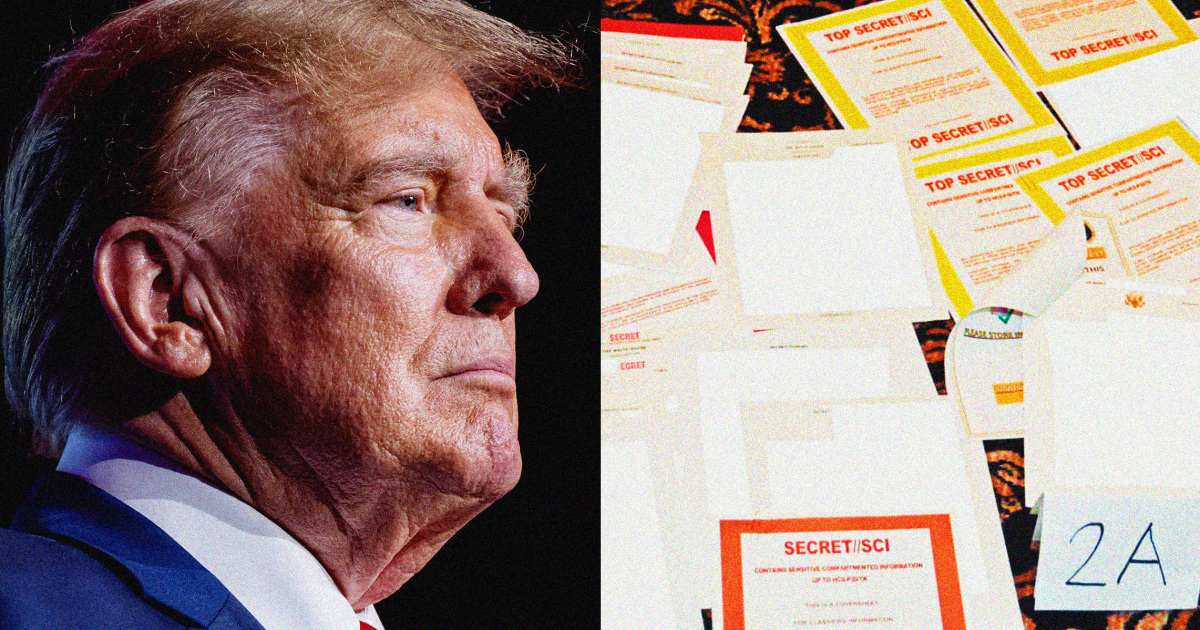

Cannon first drew public scrutiny when she was randomly assigned to the litigation over the FBI search warrant of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago compound in Florida. To the shock of many legal experts, she granted a request by Trump’s lawyers to appoint a special master to review everything the FBI seized. She cited the fact that Trump was a former president.

In December 2022, a three-member panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in Atlanta shut down the special master in a 21-page ruling that sharply rebuked Cannon, saying that she sought to create “a special exception” for Trump that “would defy our nation’s foundational principle” that everyone is equal under the law.

That ended Cannon’s involvement in the matter. But after Trump was indicted, a judge had to be randomly assigned from a small pool in the northern part of the southern district of Florida. Of four available judges, Cannon drew the case.

On Thursday, the New York Times reported that Cannon rebuffed suggestions by two federal judges that she not take the case. One cited the optics of the reversal of her special master ruling. The other said the case should be handled closer to Miami.

Cannon has repeatedly sparred with the prosecutors assigned to the case, who have appeared exasperated at times with her plodding approach.

In March, when one of the prosecutors urged Cannon “to keep things moving along,” she bristled.

“I can assure you that in the background, there is a great deal of judicial work going on,” she said. “So while it may not appear on the surface that anything is happening, there is a ton of work being done.”

But experts says Cannon has not done anything that rises to the level of Smith asking that she be removed from the case.

Cannon has ruled against Trump on important issues. In April, she decided against his claim that the case should be dismissed because the Presidential Records Act allowed Trump to consider the classified documents he allegedly kept at Mar-a-Lago to be his personal records.

But it took her months to rule. On other issues, she has forced prosecutors to jump through every technical hoop. A few weeks ago, when Smith filed a motion asking her to stop Trump from falsely saying the FBI was authorized to kill him during the Mar-a-Lago search, she blocked the motion on the grounds that the special counsel did not sufficiently consult with Trump’s lawyers before filing it. He refiled it, and it will be among the topics discussed at the marathon hearings unfolding over the next few days.

Most legal experts believe it’s unlikely the case will go to trial before the November election. That means voters will not know whether a jury believes Trump is guilty of endangering national security and obstructing justice.

“This is important information for voters to have,” Vance said.

“Had she just done her job, we would have had a verdict by now,” Scheindlin said. “It’s a shame.”