The court’s Rahimi ruling seems like a victory for gun regulation but is actually an attempt to pave the way for future extreme gun rulings.

Activists rally outside the US Supreme Court Building before the start of oral arguments in the United States v. Rahimi Second Amendment case on Tuesday, November 7, 2023.

(Bill Clark / CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

On Friday, the Supreme Court released its opinion in United States v. Rahimi. The case addressed whether domestic abusers are entitled to keep their guns under the Second Amendment, which is a critical question when you consider that a domestic abuser with a gun is an even more significant threat to women’s health than Samuel Alito with a pen. In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, the court ruled, 8-1, that people subject to a restraining order for domestic violence can lose their right to bear arms.

If you stop there, as some legal commentators want to do—in furtherance of their ridiculous narrative that the Republican-controlled Supreme Court is “moderate”—the decision might look like a surprising victory for gun regulation. But if you actually read opinions, concurrences, and dissents (seven of the nine justices offered a written opinion in this case), what you see is a group of conservatives desperately trying to square their extremist reading of the Second Amendment—and their violent rulings of the past—with the objective reality that domestic abusers should not be allowed to own firearms to menace their victims.

The conservatives’ main challenge, in this respect, is their own ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. In that case, the court invented a brand new standard for gun regulations. Leaning hard into their favorite bankrupt legal theory, Originalism, the conservatives ruled, effectively, that for a gun law to be constitutional in the 21st century, it needs to have been in existence, at least in principle, at the time the Second Amendment was ratified in the 18th century. According to Bruen, 200 years of mechanical innovations to increase the killing power of armaments means nothing, nor does our society’s evolving “policy preference” of keeping children alive and safe from gun violence. If a government wants to pass a gun regulation, it either has to find a historically analogous gun law drawn from 1791 or earlier, or we die.

This is facially stupid. I mean that in the dictionary definition of the word (conservatives love to cite the dictionary as support for risible legal contentions they cannot prove, so I’ll use their own trick and point out that Merriam-Webster defines “stupid” as “marked by or resulting from unreasoned thinking or acting”).

Already, the ruling has caused massive uncertainty and chaos. Requiring state and local governments to comb through 18th-century documents to try to translate 250-year-old legal thought bubbles into modern statutory language is a fool’s errand. Asking judges to determine whether they got it right is preposterous. How do they determine what “analogous” actually means? How much weight do they give these analogies? And how, more relevantly, do they figure out what enslavers and misogynists would have thought of a man firing a gun that has more firepower than an entire battalion of the Revolutionary Army into the air at a Whataburger when his debit card was declined?

This, in fact, is what Zackey Rahimi, the plaintiff in this case, actually did—and the question of whether he had the “right” to still own a gun that he had irresponsibly used in the past while under a restraining order taken out by his ex-girlfriend is at the heart of Rahimi. Or should be, but it’s not. Instead, Rahimi is a desperate and, frankly, flailing attempt to give guidance to lower courts on how to apply Bruen.

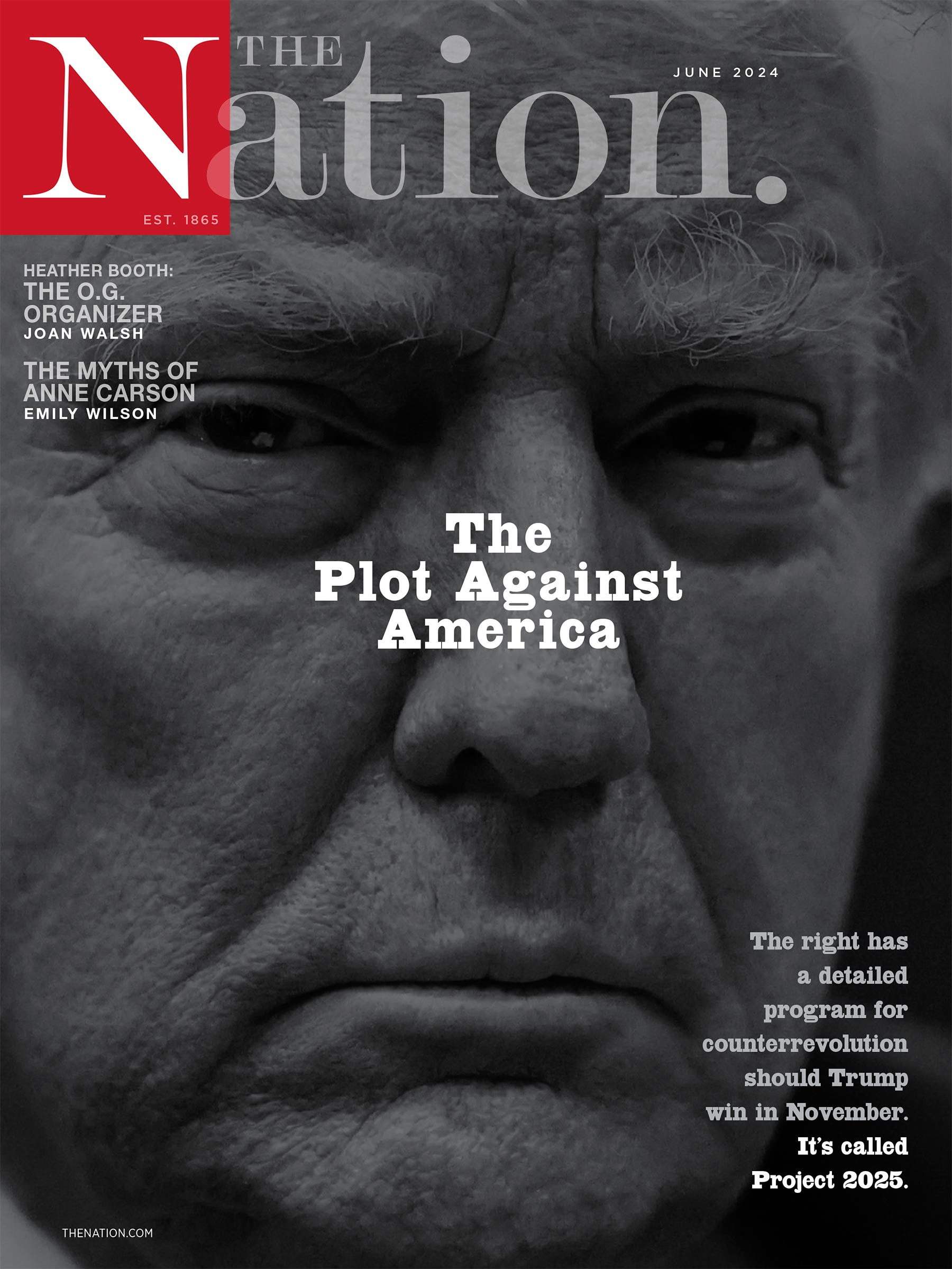

Current Issue

Roberts took the first shot at retconning Bruen to justify denying Rahimi his “right” to a gun. In his majority opinion, the chief justice argued that preventing people under restraining orders from packing heat “fits comfortably” alongside 18th-century precedent because “our Nation’s firearm laws have included provisions preventing individuals who threaten physical harm to others from misusing firearms” since its founding. Of course, the rub here is that Bruen doesn’t just require modern gun laws to gesture vaguely back toward ancient precedent; it requires them to have a “historical analogue” in the 18th century. So Roberts attempted to clarify that this analogue need not be a “historical twin” or “dead ringer”—which was great, except he didn’t really explain how “analogous” a law needs to be before guns can be taken out of the hands of violent individuals.

What he did do was offer two “analogies,” two examples of situations in which revolutionary-era folks would take away people’s guns. The first example has to do with what were once known as laws of “surety.” These laws were essentially the 18th-century version of “paroled while out on bail,” and consisted of a defendant pledging to the state not to do anything bad and that, if they did, they would forfeit a sum of money and potentially go back to prison. The second, “going armed” laws, involved preventing people from riding around on horses while wielding weapons if they could not be trusted to be nice to the people. I’m not making this up. My man was so tied up in knots that he’s using a law originally used in ye olde England to take away swords and lances from rogue knights of the realm to justify taking away a violent man’s guns in the year of our Lord 2024.

Roberts’s historical analogies are tortured and wacky, but this is what Roberts does. When he likes a law but realizes that upholding it goes against his ideological priors, he just makes stuff up. He did this with Obamacare, converting it into a “tax” to avoid giving the government its obvious power to regulate healthcare under the Commerce Clause, and he’s doing it again here. Roberts is not the most “moderate” of the court’s conservative jurists but just the most practical. That practicality comes with a side helping of shocking intellectual dishonesty, and more people would call him out for it if he didn’t occasionally come to the right conclusion through the wrong, made-up reasons.

As for the other conservatives, Justice Samuel Alito joined the Roberts opinion in full; Justices Neil Gorsuch, alleged attempted rapist Brett Kavanauagh, and Amy Coney Barrett, however, all wrote their own concurrences, each taking a crack at explaining why Bruen is still a super awesome ruling, even as they departed from it in this case.

Gorsuch basically said that if people don’t like the current conservative court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment, they can repeal the Second Amendment or quit whining. I’d argue that there is a third constitutionally permissible option: expanding the Supreme Court and filling it with judges who do not think the Constitution is a murder-suicide pact.

Kavanaugh treated us to a lecture on the importance of judges’ heeding historical precedent when deciding cases. This argument is insulting from a man who stood in front of Congress at his confirmation hearing, called Roe v. Wade “settled law,” and then voted to overturn it at the first available opportunity. I have exactly as much respect for Kavanaugh as Kavanaugh has for precedent.

Barrett argued that the terms of the Second Amendment should not merely be ossified in what the founders thought but that it should more or less be locked into what the founders thought as of 1791, when the amendment was ratified. She argued that laws passed after that date, even by the people who wrote and ratified the Second Amendment, may themselves have gotten the Second Amendment wrong.

For all three of these concurring conservatives, the ridiculous “going armed” and “surety” analogies were sufficient to get them to the right conclusion—and justify their ruling in this case. But the upshot from these concurrences is that they’ll still feel free to apply Bruen in the next gun case. And that next gun case has actually already happened. The court’s decision in Garland v. Cargill, the bump stock case, was announced last week. In the bump stock case, the court reaffirmed the violent contention that, since bump stocks were not banned in the long-ago past, they cannot be banned now. Taking Rahimi and Cargill together reveals a court that has not backed off its extremist interpretation of the Second Amendment, just one that was willing to ignore itself and make something up to stop domestic abusers and evil cavalry from having guns.

The liberal justices also authored separate concurrences—one was by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Elena Kagan, the other was by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. I might be imagining it, but as I read their opinions, I noted the distinct whiff of schadenfreude. They seemed to be having just the teensiest, tiniest bit of fun as they sat back and watched the conservatives convulse themselves over their own wrongheaded precedents, and happily poked holes in their tortured logic.

Sotomayor and Kagan dissented in Bruen, and Sotomayor reiterated many of the reasons why, but the main thrust of her argument was to make Rahimi, not Bruen, the controlling case on the question of how “analogous” a law has to be to survive the conservatives. She wrote: “In short, the Court’s interpretation permits a historical inquiry calibrated to reveal something useful and transferable to the present day.” Translation: Bruen is useless, but we could work with Rahimi.

Jackson was not on the court when Bruen was decided, so this was her first opportunity to dunk on that decision. The focus of her concurrence was how Bruen has proven unworkable for lower courts, and unknowable for state legislatures. She wrote: “The message that lower courts are sending now in Second Amendment cases could not be clearer. They say there is little method to Bruen’s madness.” She closed with this fantastic paragraph:

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

[I]n my view, the Court should also be mindful of how its legal standards are actually playing out in real life. We must remember that legislatures, seeking to implement meaningful reform for their constituents while simultaneously respecting the Second Amendment, are hobbled without a clear, workable test for assessing the constitutionality of their proposals.… And courts, which are currently at sea when it comes to evaluating firearms legislation, need a solid anchor for grounding their constitutional pronouncements. The public, too, deserves clarity when this Court interprets our Constitution.

And then there was the lone dissent from Justice Clarence Thomas. The fact of this dissent is significant because, while the eight other justices spent reams of paper explaining how courts should apply Bruen, they didn’t listen to the man who actually wrote the majority opinion in Bruen… Thomas. Thomas forthrightly explained that his colleagues are misinterpreting his own words.

Thomas writes that Bruen established that gun regulations have to have a historical precedent from the 18th century, and he writes, “Not a single historical regulation justifies the statute at issue [in Rahimi.]” This might surprise some people, but I think Thomas is 100 percent right (at least about how to apply his own terrible reasoning from Bruen). Thomas, not Gorsuch and certainly not Roberts, is the one applying intellectual consistency to this issue. (Sotomayor and Kagan are consistent too, because they thought Bruen was a bad ruling, then and now.) Thomas rightly points out that Roberts’s reliance on surety laws makes no sense, as surety laws were about money and prison, not forfeiting the right to bear arms. Thomas’s dissent could be summed up as, “When I wrote Bruen, I didn’t stutter.”

Again, if you roll the tape all the way back to 1791, you will find a society ruled by evil misogynist white men who thought beating their wives and girlfriends (who didn’t even have legal personhood) was their God-given right. Domestical violence wasn’t even considered illegal in this country until the 1920s; marital rape wasn’t deemed illegal until 1945; and domestic abuse of all kinds was socially acceptable and not commonly prosecuted until the 1970s, if we’re being extremely generous to the timeline of criminalization of domesitc violence. It makes no historical sense to say that people who did not even recognize domestic violence as a crime had a historical precedent of taking away guns from domestic abusers in 1791. There’s no freaking analogy to be had here.

The way to deal with Thomas’s correct dissent is not to engage in the intellectual dishonesty practiced by Roberts; it’s to repeal the Bruen ruling, which in just two years has shown itself to be unworkable and atrocious. Bruen wants us to find historical doppelgängers for any modern gun law, but the Rahimi case proves that such a focus is wrong.

We know more than they did in 1791. We know that women are people entitled to human rights; we know that domestic abuse is abhorrent; we know that women are five times more likely to be murdered by an intimate partner if that partner has a gun. We don’t need to know how an average white husband in 1791 would have thought about prohibiting gun ownership to domestic abusers, because that man died hundreds of years ago, hopefully from starvation while waiting for his battered wife to bring him a sandwich.

But to admit that would be to overrule Bruen, and to overrule Bruen conservative would have to admit that they were wrong and that their two-year experiment has been a legal disaster. So instead of declaring “whoops, we’re sorry” about Bruen, we’re left with this Rahimi ruling, in which the conservatives try to prop up Bruen with new, equally unworkable logic.

This sad, stupid state of affairs will continue as long as conservatives are allowed to control the Supreme Court and, with it, our gun laws. I imagine that most of the media, which can’t be bothered to read a 103-page Supreme Court ruling, will call Rahimi a step towards “moderation” from the conservative court. It’s not. What Rahimi indicates is that the court’s ruling in Bruen was legally insane, and it shows that most of the conservatives know it—but they lack the will and the strength to fix it.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The outcome is a test of how far AIPAC will go to crush progressive movements.

Richard Lingeman

This kind of penny-ante bullying reveals the intellectual bankruptcy of the pro-Israel cause.

Jeet Heer

The Academy’s film museum, seeking to placate critics who decried its earlier omission of Jewish moguls, rushes to fix its clumsy handling of a sensitive subject.

Ben Schwartz

“There are lines that cannot be crossed,” said a member of the board of California’s Public Employees Retirement System.

Left Coast

/

Sasha Abramsky

Former British media executive Will Lewis reportedly offered advice to then–Prime Minister Boris Johnson as a newspaper editor in the UK.

Chris Lehmann

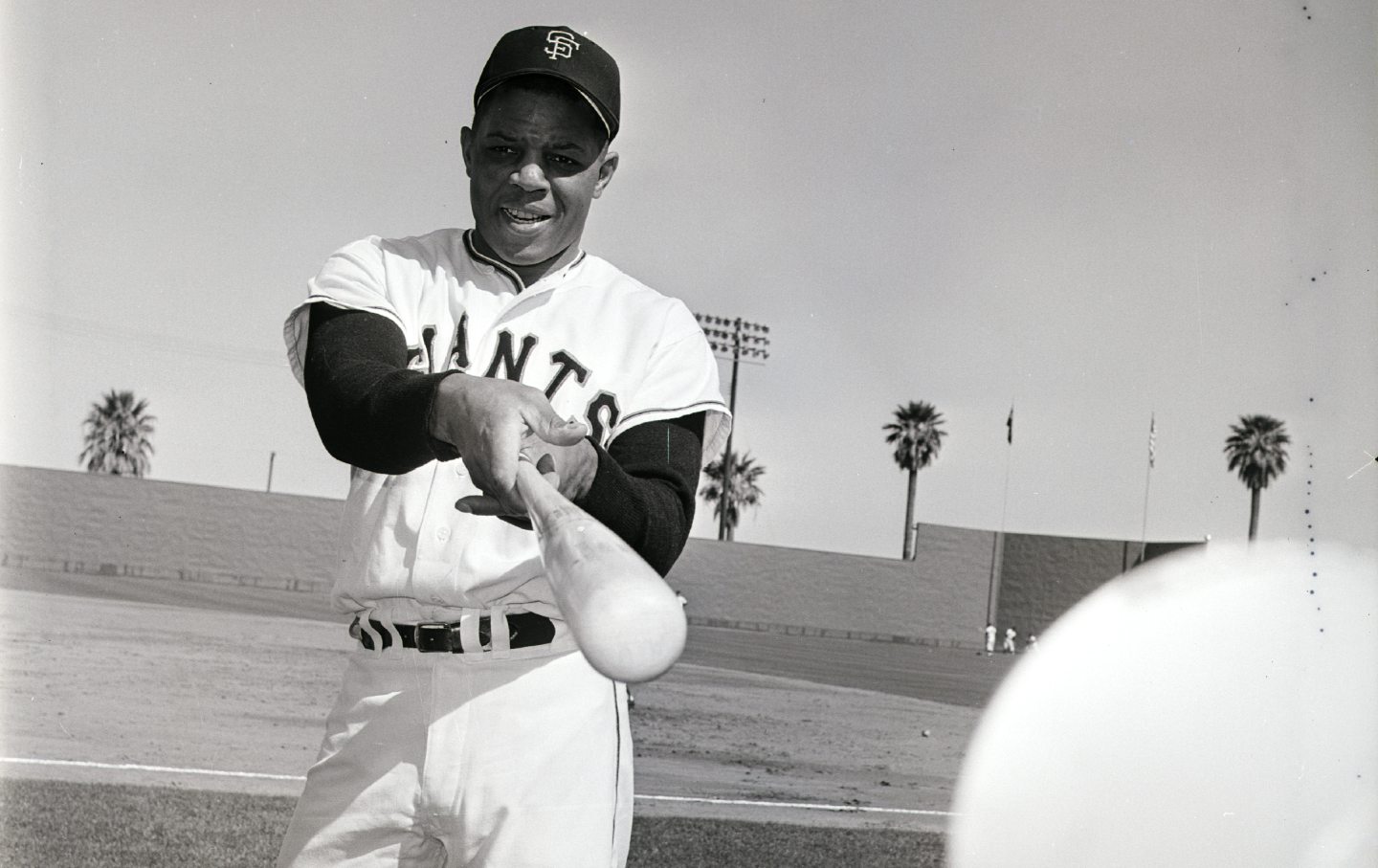

The center fielder, who died at 93, was the last surviving star who began his career in Black baseball.

Obituary

/

Bijan C. Bayne