Next week Americans will celebrate the founding of our country, but most probably don’t realize how close one hundred and sixty years ago in July 1864 America came to being permanently torn apart.

General Robert E. Lee, desperate to relieve pressure from General Grant’s troops on Petersburg, had ordered General Jubal Early and his army to march north in an attempt to draw federal troops away from the besieged Southern city. Early marched his 14,000-man-strong army north from Lynchburg for days with almost no resistance. Now with a clear path through the Shenandoah Valley to the U.S. Capitol, the Confederate general promised Lee on June 28, 1864 “to threaten Washington” and, if an opportunity presented itself, “find an opportunity to take it.”

Jubal Early

Master spy and guerilla leader John Singleton Mosby and hisRangers were ideally positioned in the Shenandoah Valley to play a critical role in supporting Early’s attack. With the subversive military tactics they pioneered and mastered, they could have impeded the movement of Federal troops while also tying up as many of them as possible. But because of a clash of personalities between the two Confederate leaders, the coordination and partnership were not to be, potentially costing the South a victory that would likely have won the war for the South.

“Mean as a dog” and an officer Robert E. Lee dubbed “my bad old man,” Early was difficult to work with. Mosby’s postwar letters indicate deep hatred for the cantankerous general. The prickly Confederate general rebuffed Mosby’s requests for direction and coordination multiple times. Riding in front of Early’s army, the Rangers could have been a force multiplier if used for reconnaissance or to disrupt Union response to the attack on Washington. Instead, Old Jube made the fatal mistake of failing to use fully the war’s master spy and his Rangers.

The full story of Mosby, his Rangers and the Union soldiers who hunted them is told in my new bestselling book, The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations. The book reveals the drama of irregular guerrilla warfare that altered the course of the Civil War, including the story of Lincoln’s special forces who donned Confederate gray to hunt Mosby and his Confederate Rangers from 1863 to the war’s end at Appomattox—a previously untold story that inspired the creation of U.S. modern special operations in World War II as well as the story of the Confederate Secret Service.

Book Jacket The Unvanquished by Patrick K. McDonnell

Early chose not to notify Mosby of his march toward the U.S. Capitol or to coordinate with him. The partisan leader found out about Early’s invasion of the North and his potential attack on Washington, only after Mosby’s men accidentally ran into Early’s quartermaster in Middleburg, Virginia. Mosby felt snubbed. The resulting actions and inactions of the two Confederates influenced the course of history.

Despite the lack of camaraderie and coordination, Mosby, on his initiative, prepared to launch a raid at Point of Rocks, Maryland in what became known as the Calico Raid. The goal was to cut the Northern line of communications by severing the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and telegraph lines. The operation began on July 3 when 250 Rangers assembled at Upperville, VA. Armed to the teeth and equipped with empty sacks for stuffing with Union loot, the Rangers rode a mile in the sweltering heat to Green Garden Mill to water their horses. The Rangers would later use the neighboring Greek-revival-style brick home, Green Garden, Ranger Dolly Richards’ family home, as one of their safe houses during the war. The mansion contains a secret trapdoor and hiding space that still exist today.

In the coming months, Richards would play an outsize leadership role in the battalion. The handsome, fearless, exquisitely dressed Confederate officer possessed sagacity and coolness under pressure that belied his nineteen years. After satiating the thirst of animal and man alike, the Rangers resumed their journey to Point of Rocks. A key hub for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the town was also a connection to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O) and a Union supply depot. Two hundred and fifty Northerners—infantry and two companies of Loudoun Rangers—guarded the town.

Through the dust and oppressive heat, a team of horses dragged a twelve-pound Napoleon up the high ground on the Virginia side of the river. The hot, sweaty work would pay off, for from that vantage, Sam Chapman, who led the crew of artillerists, would overlook the entire field of battle.

The rest of Mosby’s Rangers began the tricky business of crossing the Potomac, but Loudoun Ranger sharpshooters, concealed in bushes on the bank of a strategically-located island in the center of the river lay in wait. A phalanx of Confederates dismounted and waded cautiously into the muddy waters, uncertain of their footing. Almost immediately, the Northerners began taking aim, attempting to pick off Mosby’s men.

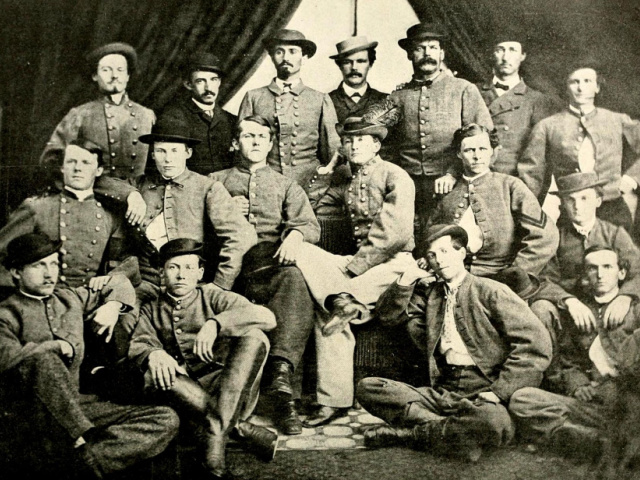

Mosby’s Rangers. Top row (left to right): Lee Herverson, Ben Palmer, John Puryear, Tom Booker, Norman Randolph, Frank Raham.# Second row: Robert Blanks Parrott, John Troop, John W. Munson, John S. Mosby, Newell, Neely, Quarles.# Third row: Walter Gosden, Harry T. Sinnott, Butler, Gentry, Public Domain

“We floundered through the water shooting, yelling stumbling over the round river stones and getting ducked overhead, rising and sputtering and firing again, the boom of our artillery proclaimed the celebration was on.”

If any of Mosby’s Rangers considered turning around, their artillery quickly dissuaded them. A round from Chapman’s gun fell short and exploded immediately behind the Rangers. Caught between the “devil and the deep sea,” the Rangers surged forward.

As the water grew deeper, the Southerners struggled. “The higher the water came up around them, the more exasperated they became.

From overhead, Sam Chapman’s Napoleon boomed. Led by Dolly Richards, Company A crossed from the island to the Maryland side and onto the towpath near the C&O, which ran parallel to the river on the northern side.

Raising the Napoleon’s trajectory, Chapman fired, and again, Union troops scattered. They scrambled across a small wooden bridge over the canal, tearing up the wooden floorboards as they crossed. The Federals then hunkered down in a small earthen redoubt perched on a small hill on the northern side of the C&O. Sheltered there from the artillery fire, they peppered Mosby’s command as his men forded the river from the island and worked their way up the riverbank to the canal.

But their gunfire was not enough to quell the spirit of the Southerners. Braving a hail of bullets, one Ranger dashed across the bare support timbers on the bridge and seized the Union garrison’s flag on the other side of the canal. Meanwhile, Dolly Richards tore wooden planks from a nearby building. As the Napoleon belched to provide cover, Mosby’s Rangers used the planks to repair the bridge. Others surged forward across the canal as artillery rounds arched overhead. In the face of the onslaught, the Loudoun Rangers fell back.

Colt pistols and a saber used by cavalrymen in THE UNVANQUISHED. Patrick K. O’Donnell

The Confederates pursued them and captured a few of their men and an officer. “I have never understood why the taking of the Point of Rocks that day was such an easy job. When you recall that our only approach to them was over a narrow towpath and which we could ride only two abreast, that we were on the farther side of a rock-ribbed canal over which it was impossible for us to charge them, it is inscrutable that they did not get into that railroad tunnel and just shoot us down as fast as we showed ourselves. But the facts are that less than two hundred and fifty cavalry rode down on them in broad daylight, re-laid the flooring on the bridge before their eyes, crossed over it, and ran them as far as the eye could reach, without loss or injury to a single man or horse. This sounds like a fairy tale, but it is literally true.”

With the Northerners out of the way, Mosby’s Rangers ransacked Point of Rocks; they severed telegraph lines and cut poles. Soon their empty sacks burst with dry goods, “bolts of cloth . . . [some] of the gaudiest prints, served as sashes which streamed from the shoulders of the wearers . . . boots and shoes, for both sexes, hung from the saddles and horse’s necks; and various kinds of tin-ware flashed back the sunlight.”

The men remained mindful of the “girls they left behind” and gathered up hats, hoops, and flashy ribbons, looking like a “parade of Fantastics.” Eventually, a considerable wagon train loaded to the gills with booty rolled to the Fauquier hills, leading one Ranger to quip, “This was quite a novel attachment to Mosby’s men, their specialty being to attach themselves to the other fellow’s wagon train.”

After the Rangers picked Point of Rocks clean, Mosby sent Early a written message: “I will obey any order you send me.” Then Mosby’s men recrossed the Potomac back into Virginia before 2,800 Union reinforcements, one-third of Washington, DC’s defenses, arrived about 2 p.m. on July 5th.

Absent several dozen Rangers who accompanied the wagon train, the less than 200 Rangers took cover on the Virginia side of the river while their ingenious leader hatched a plan to keep the thousands of Union troops tied down for as long as possible. The Rangers rode around, creating clouds of dust and occasionally parading in front of the Federals to create the illusion of vast numbers. Occasionally, they pretended that they intended to recross the river, engaging the Northerners in a series of skirmishes. “It was a kind of endless chain business by which regiment after regiment was paraded across the stage. . . . Of course, our commander had to refrain from overdoing the thing, and see to it that the program was duly varied, lest the fake should be discovered.”

On July 7, Early responded to Mosby’s message with no mention of the Calico raid and requested only that Mosby support him by once again cutting the railroad and telegraph lines and reconnoitering toward Washington. Mosby chose not to comply. So in July 1864, while over ten thousand Confederates barreled down on the nation’s capital devoid of troops Mosby and his men, the South’s most dangerous men, triumphantly paraded through the streets of Leesburg giving wagons of stolen Northern calico and finery to Southern women. A delaying action by Union forces at the Battle of Monocacy, a long march in the hot sun, and Union Reinforcements that would arrive just in the nick of time would be enough to save Washington, DC from being sacked. But had Mosby and Early coordinated their efforts, the history of the United States may have been altered that hot summer of 1864.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically-acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of thirteen books, including his new bestselling book on the Civil War The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations, currently in the front display of Barnes and Noble stores nationwide. His other bestsellers include: The Indispensables, The Unknowns, and Washington’s Immortals. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com