Everyone seems to agree that Europe is struggling—but the EU shouldn’t look to the US for inspiration.

Paris—What a difference seven years makes. In September 2017, speaking in the opulent main lecture hall of Paris’s Sorbonne University, French President Emmanuel Macron rolled out his idea of European “autonomy.” With the right reforms, he argued at length, the European project could smoothly navigate the accumulating hazards of globalization. On April 25 of this year, from the same podium at the Sorbonne, Macron gave an equally long-winded speech, this time with a markedly different undertone. “Our Europe is mortal. It can die,” Macron now warned, a line recycled on the cover of the May 4 issue of The Economist. “Europe will fall behind. We are already beginning to see this.”

Macron pored over the dire assessments that now preoccupy the European Union’s political and economic elites: The bloc was being forced to fork out billions on global energy markets; it was digitally dependent on Silicon Valley, missing out on the tech-fueled capital accumulation that had remade the US economy since 2008; and it was overly reliant on Chinese green technologies and critical minerals just when Europe’s energy vulnerability, to say nothing of the bloc’s pledges to reduce CO2 emissions, required a rapid acceleration in the deployment of carbon-neutral technologies. Claiming that GDP per capita growth in the United States had outpaced Europe’s by over 30 percent since the early 1990s, Macron cautioned that if nothing changed, the European Union faced collective “impoverishment.”

Current Issue

This kind of grim litany has become common on the European side of the Atlantic. And though there is little agreement over how to respond, there is a growing chorus about where the bloc’s problems are pointing: to the EU’s long-term economic decline relative to the other centers of global capitalism. A widely circulated 2023 report from the European Council on Foreign Relations pointed out that US nominal GDP in 2022—$25 trillion—had grown to be nearly a third larger than the combined EU and UK economies. Fifteen years early, before the 2008 crisis, Europe and the United States were essentially at economic parity. The report’s ominous title: The Art of Vassalisation.

Weeks before EU-wide elections held between June 6 and June 9 that are expected to send a record number of far-right MEPs to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, Europe remains characteristically divided along regional and political lines. Calls for Brussels to develop an EU-wide industrial policy with major public investments and subsidies funded by common borrowing are hitting up against the fiscal conservatism of the bloc’s wealthier, northern states—in a replay of the fights over austerity that dominated the 2010s.

Meanwhile, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revealed a growing gap between those who say the EU needs to anticipate a future without the United States’ security umbrella and those who view as anathema any move that might estrange Washington. Even Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz are said to have a horrible relationship, casting a chill over the German-French “couple” that is usually considered the final lever of EU decision-making.

These divides have resurfaced at a time when the bloc is especially exposed to forces from abroad. The hundreds of billions of dollars in corporate subsidies for renewable technologies provided by the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are pushing European industry further behind US companies. The United States’ spending spree is widening an investment gap that first swelled in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis. On average, net capital expenditures by US corporations dwarf investment by their European counterparts: Between 2015 and 2022, according to a recent McKinsey report, investment by US firms grew some 30 percent, while in Europe it stagnated. The EU’s population is 448 million, over 100 million more than the population of the US. Yet in the first three quarters of 2023, Europe was the destination of $90 billion in foreign direct investment in new capacity, while the US attracted $300 billion, thanks in part to the rollout of the IRA.

European leaders also fear the flood of low-cost electrical vehicles and other renewable-energy technologies from China. As European states struggle to cut CO2 emissions by 55 percent in 2030 compared to 1990 levels as promised, Chinese firms are poised to dominate the electrical vehicle market and the mineral supply chains used in non-carbon technologies. Upwards of 90 percent of solar panels installed in Europe in 2023 were made in China, while 25 percent of electric vehicle sales in 2024 are expected to be Chinese imports, a share 5 percentage points higher than the previous year.

Since 2022, Europe has reduced Russian gas imports, which have fallen from nearly 40 percent of imports before the invasion of Ukraine to around 10 percent in 2023. But a similar “de-risking” from China through targeted tariffs and import restrictions could prove even harder. After cheap Russian gas, the sale of high-value-added hardware to China has been the other pillar of Germany’s industrial base, the main engine of the broader European economy. Reuters is reporting that the United States looks likely to be Germany’s largest trading partner in 2024, after eight years in which China held the top spot. But as a replacement market, the United States could prove equally unreliable, depending on the administration in the White House.

There are ways the European Union could revive its stalling economy: It could develop new supply chains for critical metals, for example. It could match the largesse of the IRA to protect an industrial base around renewable energies. But what will be far harder to change in the medium term is Europe’s position in the global energy market. As International Energy Agency director Fatih Birol told the Financial Times in early April, Europe is reeling from “two historic monumental mistakes”: prematurely weaning off nuclear power (especially in industrial states like Germany) and becoming dependent on Russian gas.

The doomsday scenario of winters without power have not panned out, thanks in part to increased liquified natural gas imports from the United States. But it has come at a cost: Europe has been priced into a structural disadvantage, what Matthieu Auzanneau, president of the environmental policy think tank the Shift Project, likens to an additional subsidy helping to drive the US investment boom. Although the 2022 peak has receded, average megawatt-per-hour prices paid by European firms still hover between twice and three times the cost paid by American competitors, which are riding Washington’s decision to double down on shale-gas extraction.

The shale revolution offered “a late boon to American power,” Auzanneau said. “Western Europe is inexorably in a position of weakness when it comes to its access to energy and is increasingly dependent on the United States, whose shale exports have become indispensable. Relatively high energy prices are here to stay.”

Hoping to ride an anti-environmentalist backlash, the far right is campaigning on the idea that EU rules have burdened Europeans with regulations that China and the United States will never impose on their own businesses. When farmers across Europe launched tractor caravan protests this winter, for example, the far right saw them as signs of popular rejection of the environmental regulations forced on them from Brussels.

But the pressure to restore “competitiveness” is not coming just from the far right. Macron has called for a “regulatory pause” on the standards adopted in Europe’s Green Deal, the package of norms and environmental standards that the EU has adopted since 2020 and that are designed to bring the bloc to carbon neutrality by 2050. Last year, when the European Parliament adopted a plan to phase out new combustion engine cars by 2035, Germany and its powerful industrial lobby torpedoed the regulation, fearing that European automakers would be unable to resist Chinese imports in a sector that has long been a bedrock of Europe’s industrial base.

This pushback exposes the weaknesses of Europe’s climate strategy. Europe’s Green Deal and newer initiatives like the Net-Zero Industry Act “are essentially about legal norms and regulations,” explained Clara Léonard, an economist with the Institute Avant-Garde. “There’s no global investment strategy like what we’re seeing in the United States.” The onus for fiscal stimulus and subsidies has largely been left up to individual nation states, with widely varying degrees of fiscal maneuverability.

Faced with the scale of investments needed for the renewable transition, fiscally conservative states like Germany and its northern European partners still resist calls for common, EU-level borrowing. The EU’s budget remains about 1 percent of the bloc’s GDP, which leaves matters of industrial and economic policy largely to individual member nations.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Checks on member-state deficit spending, however, were reinstated this winter, and they risk widening the gulf between nations with the financial leeway to invest and those without. “Europe’s budget rules create an imbalance because we have, on the one hand, objectives for debt sustainability, and on the other hand, objectives for reducing emissions,” Léonard said. “But because there are only budgetary rules, and not climate rules with sanctions and oversight, that leads to an implicit hierarchy in favor of financial sustainability over environmental sustainability.”

These taboos could cement the EU’s investment gap relative to the United States. All things told, it points to a replay of the post-2008 scenario when the United States was more flexible than Europe in pursuing deficit-spending and fiscal stimulus, reaping the benefits of the dollar’s position as global reserve currency.

Without a comprehensive industrial deal, the main thrust for shoring up European “competiveness” is on trade policy and market integration. Former Italian prime ministers Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi have been tapped to draft reports that are expected to influence the next European Commission, led since 2019 by Ursula von der Leyen. Letta’s report was released in April, while Draghi, who presided over the European Central Bank between 2011 and 2019, gave a preliminary speech on April 16 outlining his conclusions, which are expected to be released in June.

They both argue that Europe’s common market has failed to live up to its original promise to become an integrated economic zone. While China and the United States boast enormous domestic markets in everything from basic goods and services up to capital investment, Europe’s remain fragmented. This means that outside of legacy conglomerates in sectors like heavy industry or luxury goods, the EU has struggled to foster business “champions”—to use the lingo common in Brussels. For example, Letta and Draghi ogle a US telecommunications market dominated by three firms, and they urge the EU to force a series of mergers between the EU’s more than 34 telecom companies. They call for similar concentration in the energy, financial, and defense industries in order to form commercial heavyweights with the scale to compete internationally.

These suggestions are symptomatic of a debate that is driven by anxieties about geopolitics and hard economic power. And while there may be nodes in the market in which concentration is “natural,” Max von Thun, Europe director of the anti-monopoly Open Markets Institute, rejects the prevailing assumption that scale equals security. “Creating single points of failure is very dangerous,” von Thun said. “Look at what happened during the Covid chip shortage because so much production was concentrated in Taiwan, which became a single point of failure. If we were to just say, ‘OK, let’s just produce all these chips in Germany,’ then we’d be creating another type of dependency, just closer to home.”

Viewed from a different angle, Europe’s weaknesses are in many ways its strengths. While avoiding the levels of corporate concentration seen in the United States, the European Union boasts standards of living that are among the highest in the world. An increasing number of people fall through the cracks of what EU leaders still like to call the “social market economy.” But the European “way of life” buttressed by strong social welfare systems and labor protections—or what remains of them—is still the envy of many.

Overzealous comparison with the United States brushes aside many of the social and cultural factors that undergird Europe’s economic model. “It’s the wrong path to go down to basically define and make all your policy decisions based on what you think other countries are doing or not doing,” said von Thun. “Europe has a more democratic and diverse economy than the US.… there’s an in-built acceptance for Europeans that markets are not magically self-correcting. They are a useful tool, but you have to direct them to certain ends.”

More on European politics

Fawning over the US’s supposed economic miracle also ignores the degree to which a great many Americans are priced out of their country’s boom. According to Zsolt Darvas, an economist at the Bruegel Institute in Brussels, if you take into account shifting exchange rates and cost of living, for example, using GDP per capita by purchasing power parity, Europe’s alleged fall off relative to the United States is far less dramatic. “If you compare economic output per hour worked, then Europe looks even better,” Darvas continued. “There’s a good reason for that: Europeans consider leisure time to be very important.”

Another element is bizarrely absent from European fears of economic decline: The European Union emits roughly half as much CO2 as the United States, a figure that, in the 2020s, is surely as meaningful a measure of economic health as any other. “I haven’t seen any credible US projections of arriving at net zero emissions with the Inflation Reduction Act,” Auzanneau said. “Where is the long-term strategy? At the end of the day, they don’t really claim to have one, besides throwing as much money at the problem as possible in the hope that, perhaps, something will stick.”

Concerns like these are being brushed aside—and so is another important question with implications for the future of Europe: What are the real economic lessons to draw from a society that seems ready to reelect Donald Trump?

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that moves the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories to readers like you.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

In Griffin Hansbury’s Some Strange Music Draws Me In, a man’s recollections of his transition opens up into a nuanced examination of gender identity’s many contradictions.

Books & the Arts

/

Grace Byron

Unlike Joe Biden, the former president benefits from international turmoil.

Jeet Heer

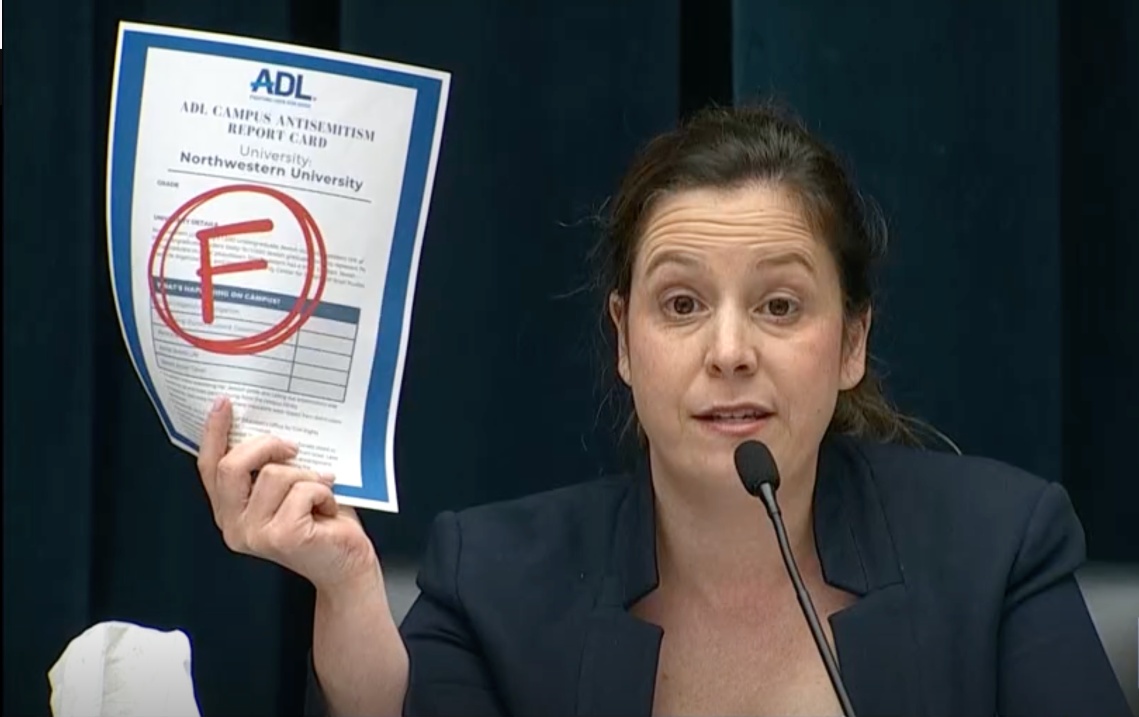

Students for Justice in Palestine called the hearing “a manufactured attack on higher education” as Republicans criticized universities for negotiating with protesters.

StudentNation

/

Owen Dahlkamp