Civil War historian David Blight, who first surfaced the history, describes the event for the Zinn Education Project:

War kills people and destroys human creation; but as though mocking war’s devastation, flowers inevitably bloom through its ruins. After a long siege, a prolonged bombardment for months from all around the harbor, and numerous fires, the beautiful port city of Charleston, South Carolina, where the war had begun in April, 1861, lay in ruin by the spring of 1865. The city was largely abandoned by white residents by late February. Among the first troops to enter and march up Meeting Street singing liberation songs was the Twenty First U. S. Colored Infantry; their commander accepted the formal surrender of the city.

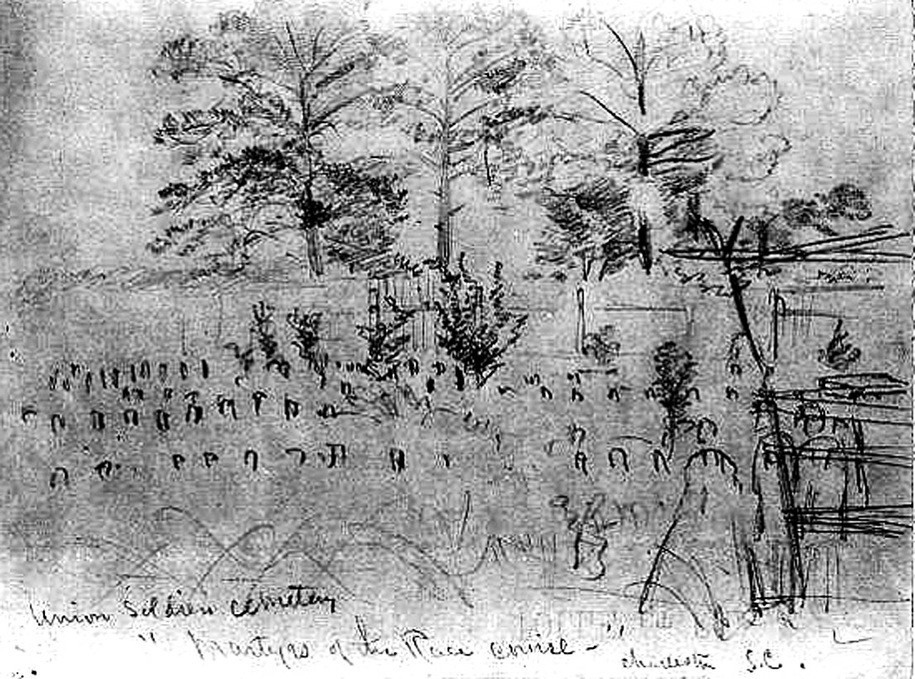

Thousands of Black Charlestonians, most former slaves, remained in the city and conducted a series of commemorations to declare their sense of the meaning of the war. The largest of these events, and unknown until some extraordinary luck in my recent research, took place on May 1, 1865. During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the planters’ horse track, the Washington Race Course and Jockey Club, into an outdoor prison. Union soldiers were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of exposure and disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand. Some twenty-eight Black workmen went to the site, re-buried the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

This had to have been an amazing scene:

Then, Black Charlestonians, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged an unforgettable parade of 10,000 people on the slaveholders’ race course. The symbolic power of the lowcountry planter aristocracy’s horse track (where they had displayed their wealth, leisure, and influence) was not lost on the freedpeople. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

Naval chaplain Padre Steve recounts what happened to the cemetery in his own Memorial Day post:

The “Martyrs of the Race Course” cemetery is no longer there. The site is now a park honoring Confederate General and the White Supremacist “Redeemer Governor” of South Carolina Wade Hampton. An oval track remains in the park and is used by the local population and cadets from the Citadel to run on. The Union dead who had been so beautifully honored by the Black population were moved to the National Cemetery at Beaufort South Carolina in the 1880s and the event conveniently erased from memory. Had not historian David Blight found the documentation we probably still would not know of this touching act which so honored those that fought the battles that won their freedom.

The African American population of Charleston who understood the bonds of slavery and oppression, the tyranny of prejudice in which they only counted as 3/5ths of a person and saw the suffering of those that were taken prisoner while attempting to liberate them stand as an example for us today. Within little more than a decade they would be subject to Jim Crow and again treated by many whites as something less than human. The struggle of them and their descendants against the tyranny of racial prejudice, discrimination and violence over the next 100 years would finally bear fruit in the Civil Rights movement whose leaders, like the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. would also become martyrs.

For those of you who have an interest in American history, I’d strongly suggest that you add David Blight’s book, “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory,” to your shelf.

No historical event has left as deep an imprint on America’s collective memory as the Civil War. In the war’s aftermath, Americans had to embrace and cast off a traumatic past. David Blight explores the perilous path of remembering and forgetting, and reveals its tragic costs to race relations and America’s national reunion.

In 1865, confronted with a ravaged landscape and a torn America, the North and South began a slow and painful process of reconciliation. The ensuing decades witnessed the triumph of a culture of reunion, which downplayed sectional division and emphasized the heroics of a battle between noble men of the Blue and the Gray. Nearly lost in national culture were the moral crusades over slavery that ignited the war, the presence and participation of African Americans throughout the war, and the promise of emancipation that emerged from the war. Race and Reunion is a history of how the unity of white America was purchased through the increasing segregation of black and white memory of the Civil War. Blight delves deeply into the shifting meanings of death and sacrifice, Reconstruction, the romanticized South of literature, soldiers’ reminiscences of battle, the idea of the Lost Cause, and the ritual of Memorial Day. He resurrects the variety of African-American voices and memories of the war and the efforts to preserve the emancipationist legacy in the midst of a culture built on its denial.

Eric Foner reviewed the book for The New York Times in 2004.

In ”Race and Reunion,” David W. Blight demonstrates that as soon as the guns fell silent, debate over how to remember the Civil War began. In recent years, the study of historical memory has become something of a scholarly cottage industry. Rather than being straightforward and unproblematic, it is ”constructed,” battled over and in many ways political. Moreover, forgetting some aspects of the past is as much a part of historical understanding as remembering others. Blight’s study of how Americans remembered the Civil War in the 50 years after Appomattox exemplifies these themes. It is the most comprehensive and insightful study of the memory of the Civil War yet to appear.

Blight touches on a wide range of subjects, including how political battles over Reconstruction contributed to conflicting attitudes toward the war’s legacy, the origins of Memorial Day and the rise of the ”reminiscence industry,” through which published memoirs by former soldiers helped lay the groundwork for sectional reconciliation. He gives black Americans a voice they are often denied in works on memory, scouring the black press for accounts of Emancipation celebrations and articles about the war’s meaning. As his title suggests, Blight, who teaches history and black studies at Amherst College, believes that how we think about the Civil War has everything to do with how we think about race and its history in American life.

Blight’s work on this period of history can also be found in “The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture,” in a chapter entitled Decoration Days: The Origins of Memorial Day in North and South. In a footnote, Blight points out:

8. New York Tribune, May 13, 1865; Charleston Daily Courier, May 2, 1865. I encountered evidence of this first Memorial Day observance in “First Decoration Day,” Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. This handwritten description of the parades around the Race Course is undoubtedly based on the article by the New York Tribune correspondent named Berwick, whose name is mentioned in the description. The “First Decoration Day” author, however, misdates the Tribune articles. Other mentions of the May 1, 1865, event at the Charleston Race Course include Paul H. Buck, The Road to Reunion, 1865–1900 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1937). Buck misdates the event as May 30, 1865, does not mention the Race Course, gives James Redpath full credit for creating the event, and relegates the former slaves’ role to “black hands “strewing flowers” which knew only that the dead they were honoring had raised them from a condition of servitude” (120–21). Whitelaw Reid visited the cemetery in Charleston founded on that first Decoration Day, making special mention of the archway and its words in his account of his travels through the conquered South: “Sympathizing hands have cleared away the weeds, and placed over the entrance an inscription that must bring shame to the cheek of every Southern man who passes: ‘The Martyrs of the Race Course.'” Whitelaw Reid, After the War: A Tour of the Southern States, 1865–1866 (1866; reprint, New York: Harper and Row, 1965).

Blight describes the importance of the Civil War in this three-part lecture for the Civil War Sesquicentennial.

Here is Part 2 and Part 3.

I take time out every Memorial Day to remember my own family members who fought in that war, even though this is a day of remembrance for those who died in battle. Thankfully, my Black enslaved ancestor Dennis Weaver was not killed, though he had a terrible time getting his military pension. I wrote about him in 2009’s “Ode to colored soldier whose name I bear.” My white second great-grandfather, James Bratt, also fought for the Union, in the 6th Independent Battery, Wisconsin Light Artillery, and survived. What is important to note, when remembering those Black soldiers who served, is that many of them died.

By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well. Black carpenters, chaplains, cooks, guards, laborers, nurses, scouts, spies, steamboat pilots, surgeons, and teamsters also contributed to the war cause. There were nearly 80 black commissioned officers. Black women, who could not formally join the Army, nonetheless served as nurses, spies, and scouts, the most famous being Harriet Tubman (photo citation: 200-HN-PIO-1), who scouted for the 2d South Carolina Volunteers.

The African American Civil War Memorial and Museum website talks about the origins and importance of the United States Colored Troops’ contributions to the American Civil War.

The United States Colored Troops made up over ten percent of the Union or Northern Army even though they were prohibited from joining until July 1862, fifteen months into the war. They comprised twenty-five percent of the Union navy. Yet, only one percent of the Northern population was African American. Clearly overrepresented in the military, African Americans played a decisive role in the Civil War.

In July of 1862, Congress passed the Militia Act of 1862. It had become an “indispensable military necessity” to call on America’s African descent population to help save the Union. A few weeks after President Lincoln signed the legislation on July 17, 1862, free men of color joined volunteer regiments in Illinois and New York. Such men would go on to fight in some of the most noted campaigns and battles of the war to include, Antietam, Vicksburg, Gettysburg, and Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign.

On September 27, 1862, the first regiment to become a United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiment was officially brought into the Union army. All the captains and lieutenants in this Louisiana regiment were men of African descent. The regiment was immediately assigned combat duties, and it captured Donaldsonville, Louisiana on October 27, 1862. Before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, two more African descent regiments from Kansas and South Carolina would demonstrate their prowess in combat.

If you visit Washington, D.C., be sure to check out the museum whose mission is “to preserve and tell the stories of the United States Colored Troops and African American involvement in the American Civil War.”