Edith Bouvier Beale at her home “Grey Gardens” in January 1972 in New York. A 1975 documentary by that name explores the reclusive lives of Beale and her mother, living in their dilapidated house with over 50 cats.

Tom Wargacki/WireImage

hide caption

toggle caption

Tom Wargacki/WireImage

Republican vice presidential nominee Sen. JD Vance’s criticism of prominent Democrats as “childless cat ladies” has unleashed fury among women, with many now reclaiming the age-old sexist trope as a call to action this election season.

In a 2021 interview with Fox News host Tucker Carlson, then-Senate-candidate Vance complained that the U.S. was being run by Democrats, corporate oligarchs and “a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they’ve made and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too.”

“It’s just a basic fact — you look at Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, AOC — the entire future of the Democrats is controlled by people without children,” Vance continued. “And how does it make any sense that we’ve turned our country over to people who don’t really have a direct stake in it?”

Video of the interview resurfaced on social media last week, as did an unrelated 2021 tweet in which Vance used the term “weird cat ladies” as an insult.

Vance was already facing scrutiny as former president Donald Trump’s newly minted running mate, in part for his stance on various family policies. He has called falling U.S. birth rates a “civilizational crisis,” and advocated in recent years that adults without children should pay higher taxes and have fewer voting rights.

And his cat lady comments — amplified online by Vice President Harris’ presidential campaign — did not land well, to say the least.

First, many took issue with the accuracy of his comments. Harris is the stepmother of two children, now in their 20s, who famously call her “Momala.”

Their biological mom, Kerstin Emhoff, has publicly decried the “baseless attacks” and credited Harris for being a “loving, nurturing, fiercely protective, and always present” co-parent over the last decade. Ella Emhoff, one of Emhoff’s daughters, also defended her stepmom in a post on social media, writing, “I love my three parents.”

And Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, whom Vance also name-checked, announced a month after that interview that he and his husband, Chasten, had become parents (to twins, we later learned).

Buttigieg told CNN last week that Vance made those comments “after Chasten and I had been through a fairly heartbreaking setback in our adoption journey.”

“He couldn’t have known that,” he added. “But maybe that’s why you shouldn’t be talking about other peoples’ children.”

Vance doubled down after backlash from both sides of the aisle

That sentiment was shared by many who were stung by Vance’s comments, including in the worlds of politics and entertainment.

Critics include former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, actor Whoopi Goldberg and TV personality Meghan McCain, who tweeted that Vance’s comments “caused real pain” and have been “activating women across all sides, including my most conservative Trump supporting friends.”

Even some conservative figures, like South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham and Fox News host Trey Gowdy, have publicly shaded Vance’s remarks.

Intended targets aside, many critics see the cat lady term as an insult to the growing number of women who don’t have kids, whether by choice or not.

Gun control activist and former Rep. Gabby Giffords, who survived an assassination attempt in 2011, tweeted that she and her husband, Arizona Sen. Mark Kelly — whose name has been floated as a potential VP candidate — were trying to have a baby through IVF “before I was shot and that dream was stolen from us.”

“To suggest we are somehow lesser is disgraceful,” Giffords added.

Actress Jennifer Aniston, who has spoken about her own fertility struggles, wrote on social media that she hopes Vance’s daughter is lucky enough to bear children one day.

“I hope she will not need to turn to IVF as a second option,” Aniston wrote. “Because you are trying to take that away from her, too.”

Vance slammed Aniston’s remarks in an appearance on The Megyn Kelly Show on SiriusXM on Friday, saying they were “disgusting because my daughter is 2 years old” and that even if she did have fertility problems down the road, “I would try everything I could do try to help her because I believe families and babies are a good thing.”

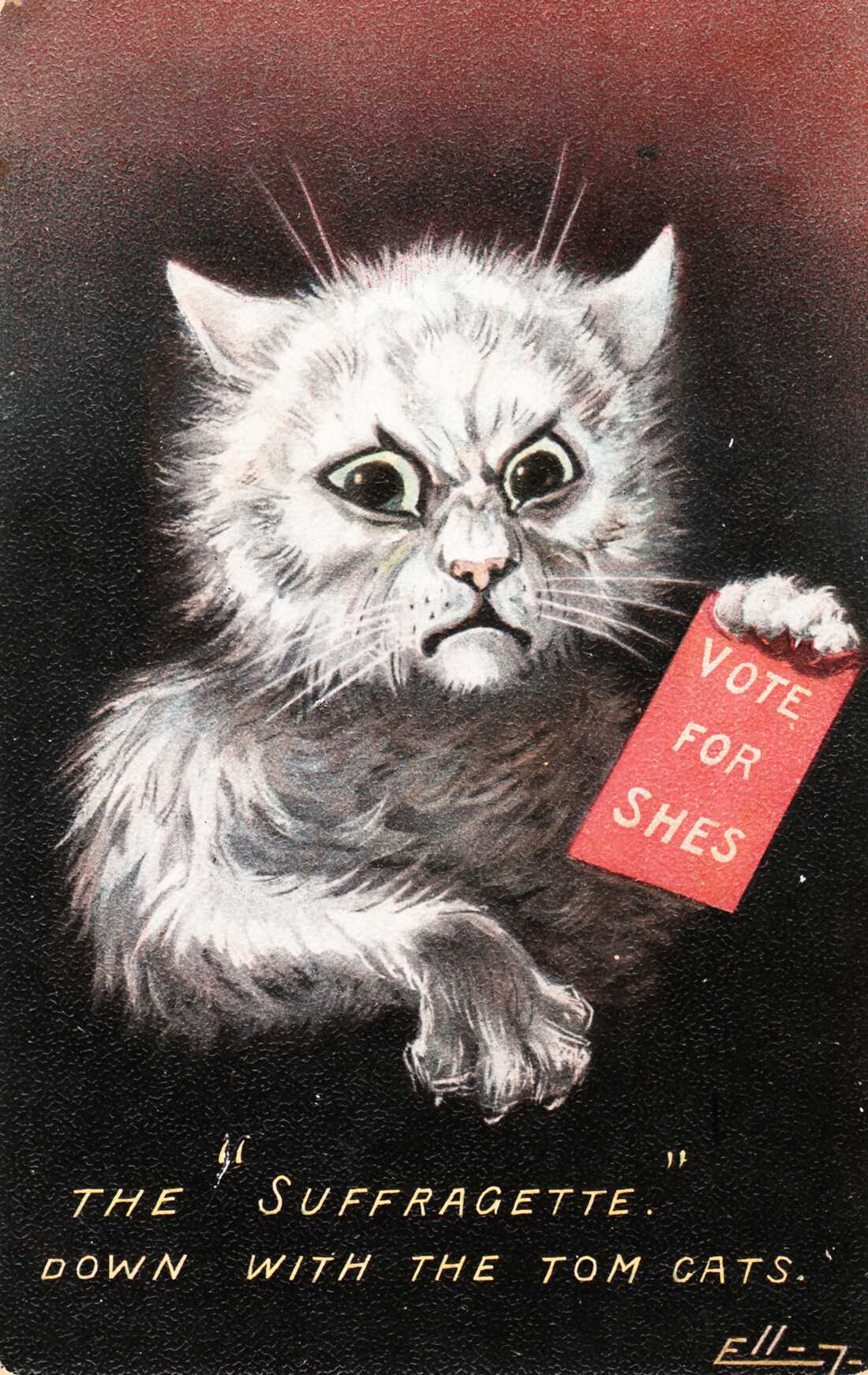

Cats were used as a symbol of anti-suffrage propaganda, but reclaimed by some suffragists. A century later, some voters see Vance’s “cat lady” comments as a call to mobilize.

Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Ken Florey Suffrage Collection/Gado/Getty Images

Vance defended his comments on Kelly’s show, saying he was not criticizing people who don’t have children, but rather the Democratic Party for being “anti-family and anti-child.”

Vance’s comments are likely to alienate single women, who make up a sizable portion of the population and a key voting bloc (63% of unmarried women voted for President Biden in 2020). And that’s not to mention the millions of cat owners across the country.

Comedian Chelsea Handler, who does not have children, noted in a video response that even the nation’s founding president, George Washington, didn’t have biological kids (he also raised two stepchildren).

“I’d like to remind you that no president in the history of the United States has ever been a mother,” Handler added.

She vowed that “all us childless cat and dog ladies are going to go from childless and crushing it to childless and crushing you in November.”

Other social media users were quick to note that one of the world’s most famous self-described cat ladies, Taylor Swift, wields a ton of influence among the voting public — and has yet to endorse a 2024 candidate.

The long tail of the cat lady trope, explained

An undated engraving showing a witch and a cat on a broom, from the middle of the 15th century.

Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Getty Images

Vance is far from the first person to invoke the trope of the crazy cat lady. The insult has literally been leveled against childless women for centuries.

We know that ancient Egyptians appreciated cats as a source of companionship (including in the afterlife) and associated them with deities, most famously in the case of the feline goddess Bastet.

But cats’ reputation soured in the Middle Ages, as they were increasingly linked to paganism and witchcraft.

While many Europeans kept cats as pets, many others came to see them as sinister (perhaps due to their handling of mice, especially at night). Twelfth-century accounts offer descriptions of the devil transforming into a black cat and of heretical religious groups worshiping cats.

People increasingly came to believe that witches — in particular, women — had the ability to shape-shift into cats, or used them and other animal “familiars” to do their bidding.

Alice Kyteler, the first person condemned for witchcraft in Ireland, was accused during her 1324 trial of possessing an incubus that looked like a black cat. Agnes Waterhouse, believed to be the first English woman executed for witchcraft (in 1566), confessed that she had directed her pet cat — apparently named Satan — to kill local livestock.

That negative association with cats migrated to colonial America, where black cats were a feature of the late 17th-century Salem witch trials. But gradually, in their wake, the trope took on a somewhat softer tone.

“In the early 18th century, as the witch trials were widely recognized as a grave miscarriage of justice, single women with cats were suddenly transformed in the public eye from frightening fiends to figures to be pitied,” Rae Alexandra wrote for KQED in 2021.

The trope of the single woman and her association with cats really took off during the Victorian Era.

In Scotland, an 1880 edition of the Dundee Courier declared that “the old maid would not be typical of her class without the cat,” and that “one cannot exist without the other,” according to the BBC.

“There is nothing at all surprising in the old maid choosing a cat as a household pet or companion,” the newspaper suggested. “Solitude is not congenial to human nature, and a poor forlorn female, shut up in a cheerless ‘garret,’ brooding all alone over her blighted hopes, would naturally centre her affections on some of the lower animals, and none would be more congenial as a pet and companion than a kindly purring pussy.”

One year later, in the U.S., Hart Ayrault wrote in Potter’s American Monthly — describing unmarried women as “having failed in the prime object of existence” — that “tradition associates her with cats and parrots, on which she is supposed to lavish all that is left of affection in her withered heart.”

A few decades later, as women began mobilizing to win the right to vote — both in the U.S. and the U.K. — they found cats used against them once again.

An English suffrage movement postcard from 1909 shows a man doing domestic chores, including watching a child and cat, while complaining he doesn’t get a vote.

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

Cats — coded as passive and associated with the home, as opposed to more active, masculine dogs — became a symbol of anti-suffragist propaganda. Many cartoons showed men at home with kids and a cat, emasculated by women’s newfound ability to participate in politics.

But some suffragists, undeterred, sought to reclaim the cat.

In April 1916, Nell Richardson and Alice Burke embarked on a 10,000-mile road trip from New York to San Francisco. They drove their two-seater “Golden Flyer” across the country to advocate for women’s right to vote, and adopted a black cat along the way.

“The little black kitten is suffering as much as we are from the heat, but he keeps under a cover, and all we can see around the corner of it is a pink nose and a youthful whisker,” Burke wrote in her diary that spring, according to the National Park Service.

The cat, named Saxon after the manufacturer of their car, became their unofficial mascot — and still stands as a symbol of suffrage. The city of Mesquite, Nev., has held an annual “Saxon the Suffrage Cat” art contest for the last several years.

The cat lady stereotype has persisted too, further memorialized in mainstream popular culture with portrayals like the reclusive subjects of the 1975 documentary Grey Gardens, Sigourney Weaver’s character in Alien (which many social media users have invoked in recent days), Eleanor Abernathy (aka Crazy Cat Lady) on The Simpsons, and the humorless, cat-loving Angela on The Office.

But, just like a century ago, feminists have increasingly sought to reclaim the title as their own. There’s plenty of crazy cat lady-themed merchandise online, and now some of it is get-out-the-vote themed.