By traditional measures, the economy is strong. Inflation has slowed significantly. Wages are increasing. Unemployment is near a half-century low. Job satisfaction is up.

Yet Americans don’t necessarily see it that way. In the recent New York Times/Siena College poll of voters in six swing states, eight in 10 said the economy was fair or poor. Just 2 percent said it was excellent. Majorities of every group of Americans — across gender, race, age, education, geography, income and party — had an unfavorable view.

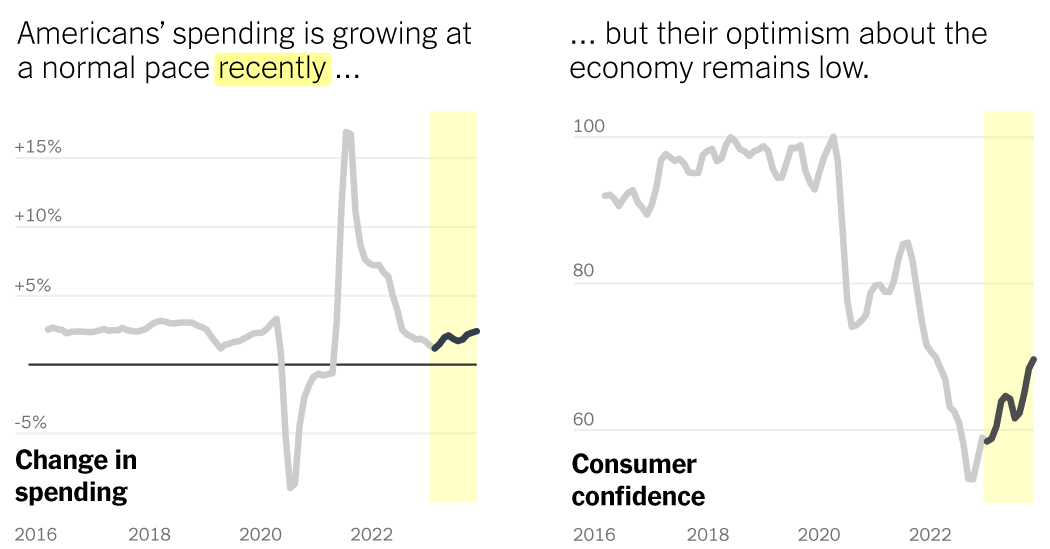

To make the disconnect even more confusing, people are not acting the way they do when they believe the economy is bad. They are spending, vacationing and job-switching the way they do when they believe it’s good.

“People say, ‘Economists don’t know why we’re unhappy? Just look at the prices!’” said Betsey Stevenson, an economist at the University of Michigan who worked in the Obama administration. “We’re looking at the prices, and we’re wondering, why are you buying so much stuff?”

“People have faced higher prices and that is difficult, but that doesn’t explain why people have not cut back,” she said of a phenomenon known as revealed preference. “They have spent as if they see nothing but good times in front of them. So why are their actions so out of whack with their words?”

The question has led to a variety of recent attempts to explain the disconnect, which could be pivotal in the 2024 election. In the poll, 59 percent of voters said Donald J. Trump would do a better job on the economy, compared with 37 percent of those who said Mr. Biden would.

We called back voters who said the economy was “poor” or “only fair” to find out why they felt that way, when the metrics, and often their personal finances, tell a different story.

Many said their own finances were good enough — they had jobs, owned houses, made ends meet. But they felt as if they were “just getting by,” with “nothing left over.” Many felt angry and anxious over prices and the pandemic and politics.

Those feelings may be driving attitudes about the economy, economists speculated, sounding more like their colleagues from another branch of social science, psychology.

“The pandemic shattered a lot of illusions of control,” Professor Stevenson said. “I wonder how much that has made us more aware of all the places we don’t have control, over prices, over the housing market.”

Inflation weighed heavily on voters — nearly all of them mentioned frustration at the price of something they buy regularly.

“Gas prices are obscene,” said Leslie Linn, 47, a restaurant manager in Carson City, Nev. “I’m looking at mayonnaise for $7. It’s like, how is that even a thing? So yeah, the economy is not great.”

Dillon Nettles, 23, in Claxton, Ga., had just stopped at Chick-fil-A when he answered our call. “What used to cost you seven bucks for a sandwich and a large fry and sweet tea, now it’s $14,” he said.

Consumer prices were up 3.2 percent in October from the year before, a decline in the year-over-year inflation rate from more than 8 percent in mid-2022. But inflation “casts a long shadow on how people evaluate things,” said Lawrence Katz, an economist at Harvard. Some people may expect prices to return to what they were before — something that rarely happens (and deflation can often signal economic catastrophe).

Also, economists said, wages have increased alongside prices. Real median earnings for full-time workers are slightly higher than at the end of 2019, and for many low earners, their raises have outpaced inflation. But it’s common for people to think about prices at face value, rather than relative to their income, a habit economists call money illusion.

“Everyone thinks a wage increase is something they deserve, and a price increase is imposed by the economy on them,” Professor Katz said.

Younger people — who were a key to President Biden’s win in 2020 but showed less support for him in the new poll — had concerns specific to their phase of life. In the poll, 93 percent of them rated the economy unfavorably, more than any other age group.

Certain campaign promises aimed at them, like forgiveness of student loan debt and subsidies for child care, were struck down by the Supreme Court or didn’t pass in Congress. There’s a sense that it’s become harder to achieve the things their parents did, like buying a home. Houses are less affordable than at the height of the 2006 bubble, and less than half of Americans can afford one.

Jaeden Grimes, 21, in Avondale, Ariz., has been trying to jump-start his life since he graduated from college, working a temporary gig while he looks for a better job and his own place to live. “More than likely, half my income will go toward rent,” he said. “I was really hoping on that student loan forgiveness.”

Voters who had already achieved certain markers of economic success, like advancing in their career or owning a home, also described feeling stuck, with little money left over to splurge or make a life change. Yet overall, economists said, data shows that more people are quitting jobs to start better ones, moving to more desirable places because they can work remotely, and starting new businesses.

“Even though you hear all this stuff — we added 100,000 new jobs — it literally means nothing to me,” said Stephen Blanck, 39, who recently moved from Wisconsin to Fayetteville, N.C. “It’s all fake when it comes to how people are actually doing.”

He said he makes almost $80,000, serving in the military and working as a DoorDash deliverer, yet feels he had more spending money a decade ago, when he was two pay grades lower.

“I’m not buying fancier cars, I got a really good interest rate on my house, we have kids but they don’t cost that much,” he said. “But we really got to budget. There’s just nothing left over to invest in the future.”

Ms. Linn, the Nevada restaurant manager, is up for promotion and owns her home, with a decent mortgage rate. Yet there’s a job opening of interest in San Diego, and she’s unhappy that she can’t afford the higher living costs there, or to buy a new house with the higher interest rates.

People always have economic constraints like those Ms. Linn described, Professor Stevenson noted. In a slow job market, for example, it’s hard to change jobs — now it’s easier, but housing is more expensive.

Still, the uncertainty Mr. Blanck and Ms. Linn share about the future ran through many voters’ stories, darkening their economic outlook.

“The degree of volatility that we’ve experienced from different events — from the pandemic, from inflation — leaves them not confident that even if objectively good things are going on, it’s going to persist,” Professor Katz said.

“When things are going well, that means rich people are getting richer and all of us are pretty much second,” said Manuel Zimberoff, 26, a manufacturing engineer in Philadelphia. “And if things are going poorly, rich people are still getting richer, and all of us are screwed.”

He says Mr. Biden’s pro-union stance and investments in clean energy and infrastructure have benefited the economy. He’ll vote for him, though his ideal candidate would be a socialist: “Bernie Sanders, but 40 years younger and gay.”

Rickie Glenn, a 35-year-old police sergeant in Commerce, Ga., probably won’t vote unless Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is on the ballot. He bought a house during the pandemic, but doesn’t really care that its value is going up — what he feels are his rising property taxes. “I feel like families, it’s a lower class,” he said. “Families are just getting by.”

Economic difficulties are greater for those without a college degree, who are the majority of Americans. They earn less, receive fewer benefits from employers and have more physically demanding jobs.

Suzanne Haberkorn, 41, a bank teller in Waukesha, Wis., fears she won’t be able to get ahead with a high school education and health issues that make it hard to work. She left her job at Walmart because it was too physical, but her current job is mentally taxing. She has been denied disability because she works, she said: “They’re pretty much like, you need to be homeless and jobless and broke to get help.”

For roughly two decades, partisanship has increasingly been correlated with views about the economy: Research has shown that people rate the economy more poorly when their party is not in power. Nearly every Republican in the poll rated the economy unfavorably, and 59 percent of Democrats did.

Steven Cabrera, 35, who works for the military in Phoenix, was among the 57 percent of voters who said economic issues were a bigger priority than societal ones. But when asked about them, he was more interested in talking about other things: the visibility of transgender people, Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez of New York and, most of all, war.

He brought up U.S. funding in Ukraine and the Middle East. He wanted to know: Is that the reason our economy is “slowing down?” He wasn’t sure, but he thought it might be. He plans to vote for “the Republican, any Republican,” he said. “Democrats have disappointed me.”