Highlights

- The Boy and the Heron is Hayao Miyazaki’s first feature film in a decade, marking his return to the 2D-animated aesthetic that Studio Ghibli is known for.

- The film combines historical and fantasy elements, creating a darker and more dreamlike atmosphere compared to Miyazaki’s previous works.

- The Boy and the Heron showcases Miyazaki’s iconic art style while incorporating distinctive features like a darker color palette and textured lines, creating a visually stunning experience.

It’s something of a redundancy to introduce The Boy and the Heron one of the most important animated film events of the year. It is the most expensive Japanese film ever made, from the most acclaimed anime auteur of all time.

It is Hayao Miyazaki’s first feature film in a decade, the first Studio Ghibli film released in the US following the studio’s ownership change to Nippon TV, a return to the 2D-animated aesthetic Ghibli is known for following the less-than-stellar reception of 2020’s CGI-animated Earwig and the Witch. It’s already eclipsed Wish, the centenary celebration of the Walt Disney Animation Studio, at the global box office.

Why Howl and Sophie are the Best Ghibli Couple

Sophie and Howl from Howl’s Moving Castle are the perfect Ghibli couple. What makes their relationship so unforgettable?

Familiar Themes, Stylish Execution

The establishing setup to The Boy and the Heron occurs when the titular boy, Mahito, is forced to flee Tokyo in the waning days of WWII after his mother’s death, finding himself on a country estate that harbors curious connections to an unseen fantasy world, if Spirited Away almost had certain affinities with The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe. If Spirited Away is a film in which a modern twenty-first-century Japanese child’s world collides with a world of whimsically monstrous yokai, The Boy and the Heron is darker, one in which both the fantasy world and the historical worlds are both sort of dealing with parallel senses of fatalism. Mahito learns from a series of duplicitous characters–the titular Heron not least among them–that his mother may still be alive within the confines of the bizarre fantasy world that his caretakers warn him of in ambiguous whispers. In some ways the fantasy of the film has a sort of internal logic that is tighter than that of other Miyazaki fantasies, but in others it feels the most hushed and dreamlike. The human characters of the film are oftentimes strong and silent; the many talking birds throughout the film, not so much.

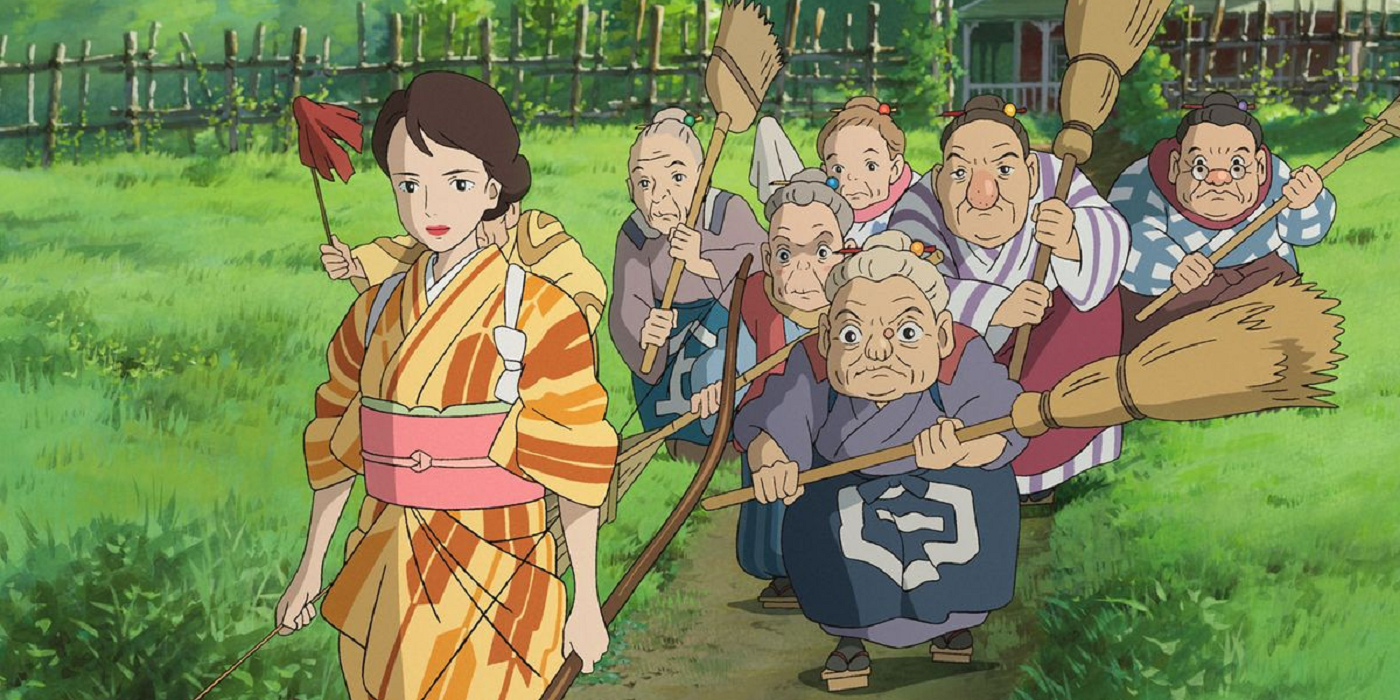

On an artistic level, The Boy and the Heron contains much of Hayao’s iconic art style as seen in his previous films, while also incorporating a few distinctive features. The color pallet is very dark compared to many of his other films, and there are liberal usages of textured lines that come in and out of view to convey depth on characters or set pieces, almost like in a manga. Miyazaki’s cinema has long been one of aerial movement, taking artistic pride in the understated dynamism of everything from the airplanes of Porco Rosso and The Wind Rises, to the magical flights of Kiki’s Delivery Service and Laputa, to even the simple rippling breeze shown on the grassy hillsides of the Japanese country.

In The Boy and the Heron, both the vintage technology and machinery of 1940s Japan and the supernatural magical realism of the fantasy, all carry themselves with similar meandering charm. Much of the film’s interior aesthetics have an aged, damask feel akin to something like Windsor McKay or Moebius, the great Western comic artists who did so much to inspire Miyazaki. Going beyond that, certain visuals later in the film almost have a sort of Salvador Dali-esque combination of grotesque warping and lavish decadence.

The Heartbreaking Reason Hayao Miyazaki’s Son Watches His Movies

While Hayao Miyazaki’s films bring joy to millions of people, the reason why son watches them is far more heartbreaking.

Darker Ghibli Magic

It is a film that invites interpretations on different levels, yet hardly beats them over the head to decisively “figure out” any single meaning in particular. The true scope of the fantasy realm feels very large and unexplored, perhaps even unexplorable, connecting different realities in subtle ways very differently from modern “multiverse” plotlines, the most loaded and buzzy of contemporary Hollywood writing devices. There’s an understanding as the film goes on that the different realities Mahito traverses have engaging and subtle impacts that he himself may have some connection in shaping, but every action that the characters take is often balanced with Miyazaki’s subtle, quiet magic that just exists for its own sake. In fact, the biggest complaint that could possibly come up on a narrative level is that it feels like too many things simply happen on their own, but this is hardly new for Miyazaki and hardly an issue for those willing to entertain the film’s dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish tone. The most memorable dreams are often those that hardly have a singular meaning, operating on their own internal logic and inviting introspection rather than any singular authoritative meaning. Miyazaki as director here has accomplished precisely as much.

There’s a case to be made that The Boy and the Heron doesn’t reach the same emotional pull as some of Miyazaki’s smaller-scale works, but it provides everything the director is known for in a darker, stylish new rendering. Miyazaki is staying comfortably in the themes and overall style that he has mastered over the decades, while still delivering unique flourishes, some baroque, some grotesque, that take it beyond simply being merely a retread of his previous work. The Boy and the Heron is nowhere near as dark as Grave of the Fireflies, but much less innocuous and family-friendly than, say, My Neighbor Totoro. Much of the film is otherworldly and beautiful, some of it grotesque, the grotesquerie of wounded, bleeding birds or long dripping tongues becoming mesmerizing in their own otherworldly way. Miyazaki here has done what he knows how to do best, provide a work that feels worthy of watching, rewatching, and contemplating on his own terms. And those terms have resulted in one of Studio Ghibli’s most adventurous fantasies yet.

Film: The Boy and the Heron

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

MPAA Rating: PG-13

Rating: 4.5/5

The Boy and the Heron is currently in theaters. North American distribution is being handled by GKIDS.