At the Game Developer Conference last month, Glow Up Games co-founder and CXO Latoya Peterson contributed to a series of micro-talks around sustainability, calling out the fundamental flaws of games funding.

Peterson was talking alongside Cornerstone Interactive Studios’ Lisette Titre-Montgomery, ProbablyMonsters’ JC Lau, Oculus Publishing’s Shana T Bryant, and Outerloop Games’ Chandana Ekanayake, in a collective presentation called “The Way We Work: Embracing Human Sustainability in Game Development.”

Peterson has had three careers, as she put it during her talk. She started as a writer, blogger, and radio/TV host, then transitioned into newsroom management and sports news, along the way working for the likes of Al Jazeera, ESPN, Disney, and many more, in a career spanning 20+ years. She co-founded Glow Up Games back in 2019 with Mitu Khandaker, with the studio being one of the first all-women-of-colour companies to have raised over $1.5 million in funding.

“We are seeing layoffs as the solution to cash flow problems… But in the games industry, funding is that invisible hand that is controlling labour”

She started her talk by pointing to a Mother Jones article from Hannah Levintova called ‘The Smash-and-Grab Economy’, looking at the real-life impact of private equity investment, how it exploits organisations, and turns them into another commodity.

“As you think about that and about the ways in which games funding is structured, you start seeing a lot of similarities,” she explained. “I came from journalism, and a lot of journalism over the last ten years has been managing through downturns [and] layoffs, over and over again. I was at ESPN [for] three years and there were five distinct rounds of layoffs.”

She similarly went through layoffs at Al Jazeera in 2014, coming into work one day only to realise her entire team was laid off and no one had told them.

“Of the team of 50, I was one of nine left,” she recalled. “Those kinds of experiences change you. A layoff is not something that happens just on a balance sheet. It’s not just numbers. It also impacts people, both those who have to leave and those who stay. And so after that, I took my career as an executive a lot more seriously, figuring that if I was going to do this, I could do this differently, that people wouldn’t have to suffer the way that I saw my team suffer that day.”

When she got into the games industry, she realised things were “eerily familiar,” especially considering the layoffs waves over the past couple of years.

“You can see all of these different headlines coming through, where time and time again, we are seeing layoffs as the solution to cash flow problems,” she said. “The argument that I’m making today is that, you know, we have this whole fear about the invisible hand that controls the markets, and particularly there’s a lot that we can talk about in capitalism [and] the free market economy. But in the games industry, funding is that invisible hand that is controlling labour.

“JC [Lau] mentioned unions being a powerful form of collective action, but for those who came from journalism or film, where unions are plentiful, one of things you learn is that unions don’t fix cash flow. They cannot help in that respect. They might be able to negotiate a better severance package. But they can’t fix a structural issue, like funding. So we’re going to talk a little bit about what’s going on and what’s impacting the labour market, how games are funded, how indie studios are funded, and how even large studios are still at the mercy of this house of cards that is the funding system that we’ve built.”

“In the eyes of venture capital, labour is not an asset”

First looking into publishing, Peterson shared that while Glow Up did explore that route, it wasn’t successful due to publishers’ often narrow criteria, and the necessity for your game to fit into their “preferred box.”

“There’s so many ideas and so many talented folks who want to create games. But when you’re trying to find someone that is going to fund your game, a lot of times you are trying to fit into their vision for what they want. And if your vision is too far outside of that, you might not ever get funding regardless of the quality of your idea.

“One of my favourite publisher rejections was essentially all green lights, they loved the concept, they loved what we were doing, they agreed that the market we were serving – gamers of colour and women in particular – were underserved, they knew this was important, they could see the cultural impact. But their response to us was: ‘We have never tried to speak to this audience, we’re not going to be able to help you, we hope it works’.”

So Peterson and her co-founder ended up going the venture capital route, which still very much needs to fit a “pattern,” she said. (This is something we very recently discussed with Lisette Titre-Montgomery as well, who argued that finding the right VC partnership is like marriage.)

“If you all look at who’s getting funded, you’ll start to notice it’s very ‘winner-take-all’. [According to Pitchbook] last year there were 572 deals done representing about $4.1 billion, but that was poured into 500 studios. It’s a very, very small percentage of who’s active, who’s operating, and what’s currently happening.

“One of the things to also remember is that they’re looking for a profile that they feel like is going to be successful. There’s a disproportionate amount of people who have led large games studios… If you have not led a large game, if you have not led a large studio, you are seen as a risk. [The] culture doesn’t allow for folks like us to come up. There becomes that intractable issue and it’s very hard to solve it. The other issue is that in the eyes of venture capital, labour is not an asset.”

“Funding is a house of cards where you’re jumping from deal to deal hoping that you can get enough runway to last… or cash back out before you run out of money. For most people when they play that game, [they] lose”

She noted that, historically, the games industry has always invested a lot in its people, its teams, and its institutional knowledge. Unfortunately, this is often seen as a weakness as far as funding goes.

“The more employees you have, the more vulnerable you look, the more funders are going to wonder why you’re not using contractors, why you are trying to offer people benefits… One of the running jokes I have about founding Glow Up is that starting a for-profit studio in America is going to turn me into a socialist,” she laughed.

“The amount of questions you get about health insurance, how you help people, is difficult, especially when you’re just a small studio owner trying to make sure you have enough runway to get to the end of the project.”

She added that big studios are not protected from the headwinds indies are experiencing, pointing to the ill-fated example of Volition, shut down by Embracer in August 2023 after 30 years of existence.

“Saints Row is an enormous franchise, and if you look [at] what happened, a $2 billion dollar deal with the Savvy Games Group fell through and that took out the studio. Once again, gaming funding is essentially a house of cards where you’re jumping from deal to deal hoping that you can get enough runway to last, get you ahead, or cash back out before you run out of money and opportunity. And for most people when they play that game, [they] lose.”

Volition is only one of many studios that have recently shut down or gone through redundancies, among a number so high that listing them all here would take too much space. For what it’s worth, GamesIndustry.biz did not feel the need to create a ‘Layoffs’ article tag until August 2022, and since then 174 articles have been published under that tag. Games funding that had emerged out of the COVID crisis has dried up, Peterson continued, pointing to figures from Pitchbook (see image below), and tens of thousands of people are out of a job.

“We are facing a crisis and this crisis is being sparked by funding,” she added. “The vast majority of people will never get venture capital to fund projects, particularly for Black women entrepreneurs. We got – and this was last year when it was still okay – 0.67% of all venture capital funding. That number is smaller in games.

“When I look at Black women who have raised money, it’s [Glow Up], Jessica [Murrey] from Wicked Saints, it’s [Lauren Frazier] from Ramen VR… It’s not a lot. There are more men from Riot who will ever be able to raise. We told this joke at ESPN: there’s more men named John on the management team than women. And I feel like we’re starting to develop one for funding and games.”

Going back to common sources of funding in games, she emphasised again that a wide majority will never get VC funding, and that angel funding “only goes so far.” So it leaves borrowing from family and friends, cash flow from other games, or crowdfunding, which all have their own issues and create a “constant cycle of instability,” making it very hard to guarantee stable employment to a team.

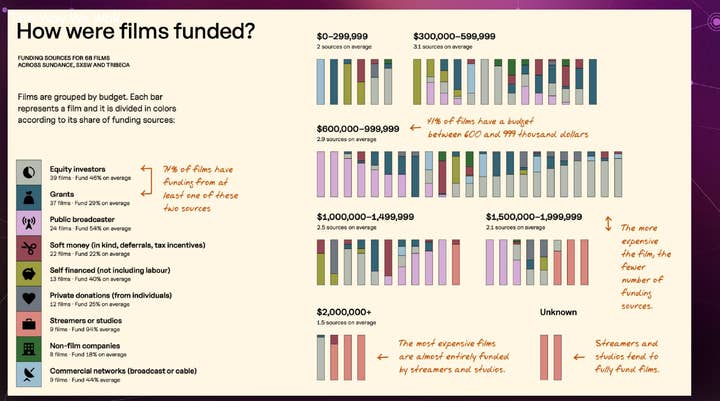

Now when comparing the situation to film, it’s night and day – though Peterson was keen to clarify that film is obviously not perfect either. The slide below shows a wide variety of funding sources for films that were featured at Sundance, SXSW, and Tribeca:

“The diversity of funding sources that you see on the left allows a little bit more stability in these projects,” Peterson said. “So even things just like finishing funds, a lot of times in game dev that comes through a publisher who still wants to take 50 to 70% of your game’s profits for helping you distribute, even if they didn’t necessarily put the cash down to help you make it. Versus in film, a lot of times that’s just a grant, unrestricted.”

Many countries, including the UK (which is the example Peterson highlighted), offer different types of funding, investment schemes, and tax credits, which helps bring more stability and allows for a more equitable system.

“I love the idea of soft power [in leadership]… but soft power still answers to hard money”

“That will allow for a lot of these things to start being solved, once we start asking harder questions about why we have allowed the funding to be so shaky and so focused on winner-takes-all,” she continued.

“So, just to conclude, one of the big things that we have to remember when talking about this is that we can always sit and try to improve our studio cultures and figure out where we can improve. But until we start looking at the funding landscape and ask hard questions of why it is only certain people that get funded, why it is that everyone else has to fight for scraps, as we are trying to create cultures that we believe in… Many of us are refugees from studios that burnt us out and treated us terribly.

“And yet, when it comes time to fund things and to do things differently, we are starving for the capital that we need. I love the idea of soft power [in leadership] and being able to look at the ways in which we run our studio culture, but soft power still answers to hard money. And we have to figure out a more equitable way of distributing funding in the games industry before we will see this change.”

Sign up for the GI Daily here to get the biggest news straight to your inbox