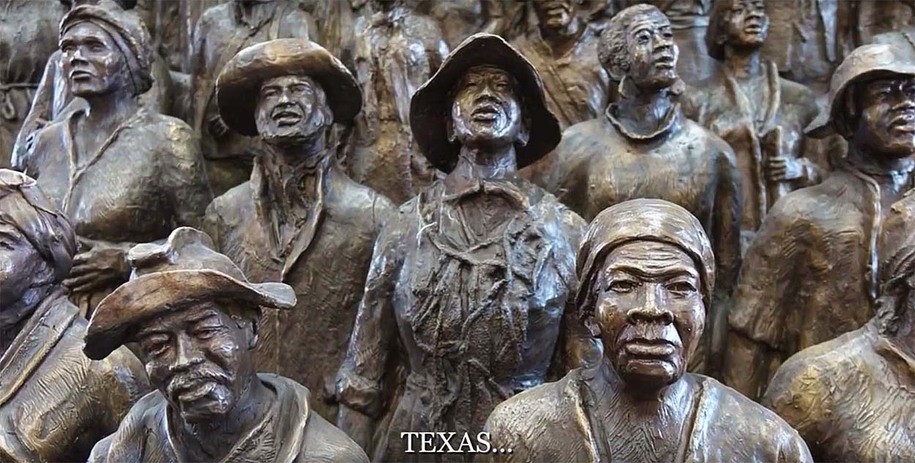

One of the most moving monuments I have ever seen was created by sculptor Ed Dwight. It encompasses not just the Juneteenth Emancipation but also the road that led to it in Texas, and the journey afterward. It sits on the grounds of the Texas Capitol in Austin. Sadly, its neighbor monuments honor the Confederacy.

The most prominent is the monument to the Confederate war dead on the Capitol’s south grounds. Installed in 1903, it depicts Davis standing atop a pedestal surrounded by several soldiers. The side of the monument reads:

Died for state rights guaranteed under the Constitution. The people of the South, animated by the spirit of 1776, to preserve their rights, withdrew from the federal compact in 1861. The North resorted to coercion. The South, against overwhelming numbers and resources, fought until exhausted.

At a time when more and more people across the U.S. are questioning the existence of shrines, memorials, and monuments to those who celebrated and fought to preserve slavery—and who also condoned and participated in terrorism against Black Americans after Emancipation—we should be fighting to replace them all with monuments like Dwight’s.

This promotional video displays the scope of the installation.

Dwight’s work was unveiled in November 2016.

The creation of the monument began in 1993, when former President George W. Bush, then governor of Texas, approved its funding. The memorial, although long overdue, was not without controversy. A “White Lives Matter” group gathered at the Texas State Capitol on Saturday, which in turn drew a counter protest.

“This has not been an easy journey,” said Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner. “And I’m not referring to the raising of money or to the construction of this monument. I am talking about the history of African-Americans of the state of Texas and where we are today.”

The Texas African-American History Memorial Foundation has raised $2.9 million for the construction, maintenance, and dedication of the memorial. The 27-foot high, 32-foot wide monument will be the last monument erected on the south lawn.

The Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture has detailed research on the history; much of it is ugly.

… in the early months of 1865, Texas newspapers still contained advertisements of slaves for sale as Texans went about their slave-holding business as usual, openly defying compliance with the proclamation. Some Texas slaves reported being in bondage as much as six years after emancipation, and after Juneteenth, blacks were murdered, lynched, and harassed by whites.

“The war may not have brought a great deal of bloodshed to Texas,” notes historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner, “but the peace certainly did.”

Slave “patrols” of whites scoured the countryside for runaway blacks, who were beaten and sometimes killed. The same held true for sympathizing whites. The fear and uncertainty about emancipated slaves was evidenced in stories appearing in the Galveston newspaper, wondering about the white citizens’ plight, economically and socially, under “a government in which we have now no voice.” Another piece, in the Galveston Tri-Weekly News, on June 21:

“This attempt to overthrow an institution that has become a part of our social system and which our entire population has believed essential to the welfare of both races, led to the war … and all we can do in our present entire dependence on the clemency of our conquerors, is to repeat to them what we have been urging for so many years … that the attempt to set the negro free from all restraint and make him politically the equal of the white man, will be most disastrous to the whole country and absolutely ruinous to the South.”

That was the mood that greeted Gen. Granger and his troops, who met no resistance at Galveston, two and a half months after Lee’s surrender and three weeks after Gen. E. Kirby Smith had surrendered the last regular Texas Confederate soldiers at Galveston Island. Granger was sent to command the Department of Texas and among his first duties was announcing General Order No. 3:

“The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor: The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Granger set up a provisional government as some of his troops continued throughout South and East Texas enforcing the “official” mandate of freedom.

And yet Juneteenth is now a celebration. Then-Gov. Bill Clements even made June 19 a legal holiday—Emancipation Day in Texas—back in 1979.

Unfortunately, the University of Texas at Austin notes, the same bill that established Juneteenth as an official state holiday also included glorification of the Confederacy.

…was submitted by Representative Al Edwards (Houston,) and sponsored by Senator Chet Brooks (Pasadena). The bill was officially entitled, House Bill 1016, 66th Legislature Regular Session, Chapter 481.

The nineteenth day of January shall be known as “Confederate Heroes Day” in honor of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and other Confederate heroes.

The 19th day of June is designated “Emancipation Day in Texas” in honor of the emancipation of the slaves in Texas on June 19, 1865.Signed by Governor William Clements June 7, 1979; effective January 1, 1980.

The PBS documentary “Juneteenth: A Celebration of Freedom” illustrates why the holiday has become an important tradition.

Talking Points Memo’s 2015 article, “The Hidden History Of Juneteenth,” gives more detail on the aftermath.

One oft-told myth has it that Texans simply did not know that slavery had ended. What Granger brought, in this telling, was good news. But if we listen to the words of someone like Felix Haywood, a slave in Texas during the Civil War, we see that this was not so. “We knowed what was goin’ on in [the war] all the time,” Haywood later remembered. At emancipation, “We all felt like heroes and nobody had made us that way but ourselves.”

[…]

Granger’s proclamation may not have brought news of emancipation but it did carry this crucial promise of force. Within weeks, fifty thousand U.S. troops flooded into the state in a late-arriving occupation. These soldiers were needed because planters would not give up on slavery. In October 1865, months after the June orders, white Texans in some regions “still claim and control [slaves] as property, and in two or three instances recently bought and sold them,” according to one report. To sustain slavery, some planters systematically murdered rebellious African-Americans to try to frighten the rest into submission. A report by the Texas constitutional convention claimed that between 1865 and 1868, white Texans killed almost 400 Black people; Black Texans, the report claimed, killed 10 whites. Other planters hoped to hold onto slavery in one form or another until they could overturn the Emancipation Proclamation in court.

Against this resistance, the Army turned to force. In a largely forgotten or misunderstood occupation, the Army spread more than 40 outposts across Texas to teach rebels “the idea of law as an irresistible power to which all must bow.” Freedpeople, as Haywood’s quote reminds us, did not need the Army to teach them about freedom; they needed the Army to teach planters the futility of trying to sustain slavery.

The memorial does not simply illustrate the history of enslavement, emancipation, and reconstruction. Dwight has also portrayed more recent Texas history—and the link between his depiction of Bernard A. Harris, Jr, the first African-American in space, and his own history is extremely interesting.

Dwight was to have been the first Black astronaut.

This video interview with Ed Dwight gives you a glimpse into his vision.

Today, Juneteenth is not just a day for remembering the ancestors and the blight that was American slavery. It is also a time to come together and enjoy socializing and lots of great food.

What’s on your Juneteenth menu?

Now that we’ve explored the history of Juneteenth and the memorial, I’d like to know how many of you have ever attended a Juneteenth celebration. Meet me in the comments for more on Juneteenth, and to talk celebrations and menus.

RELATED STORIES:

A look back at how Americans celebrated Juneteenth over the last two years

Juneteenth is a new holiday for many Americans. For my family, it’s always been personal