A reformist challenges five conservatives in the June 28 presidential vote.

Forty-five years into its existence and after 13 presidential elections, the Islamic Republic of Iran is suddenly facing its 14th, following the death of President Ebrahim Raisi, a hard-liner with a history of cruelty, in a May 19 helicopter crash.

The election comes at a critical moment. Iran is still reeling from an unprecedented internal cycle of protest and repression. It’s at a crossroads over its nuclear program: Will Tehran opt to become a military nuclear power, perhaps ending up as a North Korea–style pariah, or will it choose to negotiate something like a détente with the United States and Europe? And will Iran and its allies, including Syria, Hamas, Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthis, and various Iraqi militias, continue to risk a regional conflagration with the United States and Israel, or could a potential rapprochement ease tensions?

It’s often said, not without reason, that elections in Iran don’t matter, that all power rests with Iran’s unelected Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and that vote-counting by the Interior Ministry is opaque and easily rigged—as apparently happened in 2009 with the controversial reelection of then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Besides, skeptics argue, candidates who might challenge the system are nearly always eliminated by the ultraconservative Guardian Council, an unelected group of a dozen ayatollahs and other clerical allies, long before any ballots are cast.

But in fact there have indeed been upsets in Iranian presidential elections, and not inconsequential ones. And this year, there’s a surprising addition to the June 28 field: Masoud Pezeshkian, a reformist and advocate for rebooting the nuclear talks with the West, who’s challenged key elements of Iran’s system and who’s spoken out against the violent repression of the protests in 2023. Pezeshkian will face a panoply of five right-wing opponents ranging from a pro-establishment, fairly moderate conservative to a handful of militant extremists.

Current Issue

There are plenty of reasons Pezeshkian is a long shot, especially when measured against the moderate conservative, Mohamed Baqer Qalibaf, who’s expected to be Khamenei’s favorite. The biggest challenge for Pezeshkian, say analysts of Iran’s politics, is that disaffection, cynicism, and bitter resignation are at all-time highs among voters and such apathy is likely to lead people who otherwise might vote for a reformist to stay home. Indeed, most Iranians have not bothered to vote in recent years: In the 2021 election that saw moderate President Hassan Rouhani replaced by the lackluster, radical-right Raisi, just 48.8 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, a stunning drop from the 85 percent, 73 percent, and 73 percent that voted in the three previous races. And on March 1 of this year, in the wake of the nationwide “Woman, Life, Freedom” protest movement that shook the country last year following the death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman who’d been arrested for refusing to follow the strict hijab rules set by Khamenei, a historic low of just 41 percent found their way to the ballot box in Iran’s parliamentary election.

Overall, the reformists have lost credibility with much of the public, says Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the New York–based Center for Human Rights in Iran. Ghaemi says that Pezeshkian, a cardiac surgeon and a member of parliament from Tabriz in Iran’s northwest who served as minister of health during the reformist administration of President Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005), is a “relatively low-level guy who hasn’t excited anyone.”

Part of the reason many Iranians have lost faith in electoral politics, of course, is that in 2018 President Trump blew up the nuclear agreement negotiated by President Obama in 2015, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA. That unilateral abandonment of the JCPOA and the subsequent regime of “maximum pressure” sanctions that crippled Iran’s oil exports undermined many Iranians’ faith in the ability of politicians to better their situation, and it allowed Iranian ultraconservatives to undermine the reformist-adjacent President Hassan Rouhani (2013–2021).

Pezeshkian’s best hope is that a series of five televised debates between June 17 and June 25 allows him to persuade disaffected voters to turn out, setting him up to place in a two-person runoff election if no candidate gets more than 50 percent. But his reluctance so far to promise more than incremental change isn’t likely to inspire people. “There certainly is a chance that he can galvanize people, but he has started off slow because he has emphasized that he is not going to challenge Khamenei and the system as a whole,” Trita Parsi, executive director of the progressive Quincy Institute and a cofounder of the National Iranian American Council, told me. “Such a message may serve his goal of becoming a unifying president, but it likely undermines his goal of generating the degree of voter participation necessary to make him president. His strategy may be to only push enough to secure a second round, and then in the second round, he may not need to be as explicit of an anti-establishment candidate to generate the necessary level of enthusiasm to win the presidency.”

But Pezeshkian, half-Azeri and half-Kurdish, can be expected to draw support from both Iran’s non-Persian minorities and urban liberals in cities such as Tehran and Isfahan. And he’s signaled that, if elected, he’ll reappoint Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, an English-speaking, American-educated diplomat who oversaw the successful completion of the JCPOA in 2015 as Rouhani’s foreign minister. Zarif, a veteran diplomat who served as Iran’s UN ambassador and long had extensive contacts with senior US and European officials, was an architect of the so-called “grand bargain” proposal in 2003 that aimed to resolve a wide range of differences with the United States.

Still, more likely to come out on top is the regime favorite, Qalibaf. Called “a leading contender” by the pro-government Tehran Times, Qalibaf is a mainstream conservative who’s served as Iran’s police chief, mayor of Tehran, and speaker of the parliament. He’s a former commander of the all-powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps air force, which seems to be supporting him. And he’s notorious for having backed harsh crackdowns on protesters, once bragging about having ordered the use of live ammunition against student protesters in 2003. His track record means that advocates for liberalization of social and political life inside Iran can expect little or no change if Qalibaf wins the presidency—though his attitude toward protests and repressive laws such as the hijab rules are likely to be somewhat less extreme than those of the leading ultraconservative challenger, Saeed Jalili, a former adviser to Ahmadinejad who led the nuclear talks with the West until 2013.

Unlike Jalili and several of the other far-right candidates, Qalibaf might be open to resuming efforts to find a compromise on the nuclear issue once in office. His team has been dropping hints that staffers have reached out to US and European officials. “The advisers have emphasized Qalibaf’s willingness to ‘improve Iran’s relations with the rest of the world’ and to ‘cleanse’ the Iranian regime of ‘radical elements’ during the advisers’ conversations with foreign officials,” according to a report by the American Enterprise Institute.

Ali Vaez, Iran project director for the International Crisis Group, sees no sign yet of any contacts underway between Qalibaf’s team and Western officials. But he told me, “Certainly the next Iranian government would be interested in finding a solution to the nuclear issue. They’re not at all eager to rely on Russia and China for their economic needs, and they want sanctions relief.”

On and off, even under Raisi, since 2021 the United States and Iran have been engaged in a series of semiformal talks in an attempt to find common ground for rebooting the JCPOA or making a successor accord. Adding urgency to the issue is that the UN Security Council resolution that codified the JCPOA expires in October 2025, putting a nail in the coffin of that deal and making it much more difficult to come to an agreement. The most advanced talks were to have occurred in October 2023, but they didn’t happen in the wake of the October 7 terrorist invasion of Israel by Hamas. “It was supposed to be an attempt to start direct negotiations in October or November followed by the entire P5+1 [the six countries, including the United States, Germany, France, the U.K., Russia, and China, that signed the 2015 agreement],” Seyyed Hossein Mousavian, a Princeton scholar and former nuclear negotiator for Iran, told me. That didn’t happen, either.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

The question remains, why did Khamenei and the Guardian Council approve the candidacy of Pezeshkian at all? Perhaps it’s because the regime sees the sharply declining turnout as a sign that it is losing legitimacy, and they hope that letting Pezeshkian run would entice enough liberal and moderate voters to raise turnout at least back over 50 percent. “The reason that the deep state allowed Pezeshkian to run, as a second-tier candidate, is because they believe he won’t be able to generate the kind of support that led to the election of Khatami [in 1997],” says Vaez.

But that conceivably could backfire, leading to the aforementioned possible surprise. In the past, the landslide victory by Khatami was an unpleasant surprise for Khamenei. In 2009, a series of television debates electrified the country and allowed the pro-reformist Mir Hossein Mousavi to gain a surge of support in his run against Ahmadinejad. And the 2013 election of Rouhani, partly engineered behind the scenes by an éminence grise, the late Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, also shocked many in Iran’s conservative establishment. (In that election, Rouhani won with 51 percent of the vote, handily defeating none other than Qalibaf, at 16 percent, and Jalili, at 11 percent!)

“Iranian politics has always been unpredictable,” says a former Iranian official, who asked for anonymity. “If turnout this year is around 40 percent, the worst candidate, Jalili, will have a chance to win. If it ends up around 50 percent, Qalibaf will win. And if turnout is 60 percent or higher, then Pezeshkian has a chance.”

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

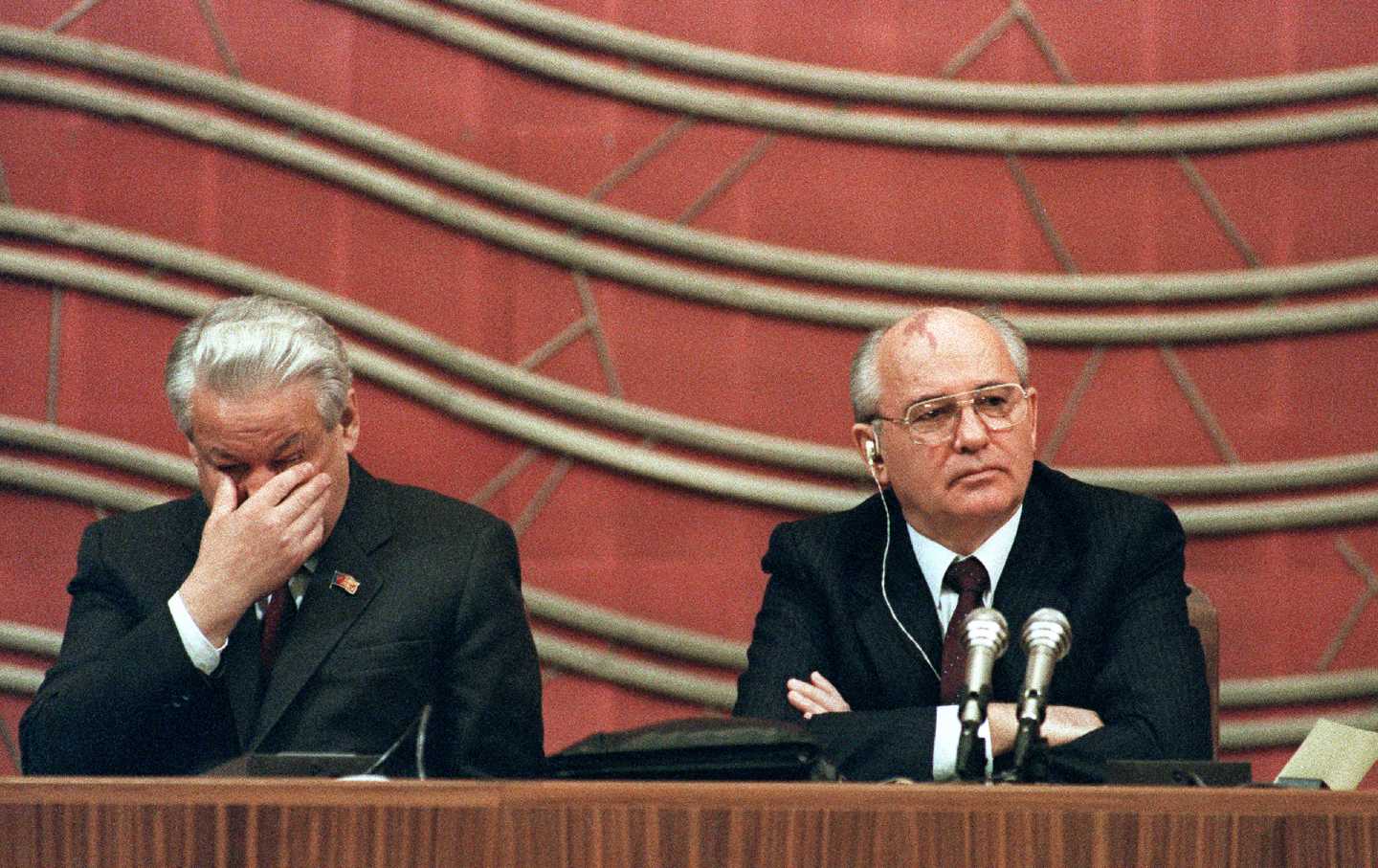

On the 35th anniversary of the First Congress of People’s Deputies in Moscow.

Nadezhda Azhgikhina

If we’re set on Armageddon, America’s existing force of nuclear submarines is more than enough.

William Astore

Global courts challenge Israeli action in Gaza.

Reed Brody