ISRO

ISROThe Moon’s south pole was once covered in an ocean of liquid molten rock, according to scientists.

The findings back up a theory that magma formed the Moon’s surface around 4.5 billion years ago.

Remnants of the ocean were found by India’s historic Chandrayaan-3 mission that landed on the south pole last August.

The mission explored this isolated and mysterious area where no craft had ever landed before.

The findings help back up an idea called the Lunar Magma Ocean theory about how the Moon formed.

Scientists think that when the Moon formed 4.5 billion years ago, it began to cool and a lighter mineral called ferroan anorthosite floated to the surface. This ferroan anorthosite – or molten rock – formed the moon’s surface.

The team behind the new findings found evidence of ferroan anorthosite in the south pole.

“The theory of early evolution of the Moon becomes much more robust in the light of our observations,” said Dr Santosh Vadawale from the Physical Research Laboratory, who is co-author of the paper published in Nature on Wednesday.

Before India’s mission, the main evidence of magma oceans was found in the mid-latitudes of the Moon as part of the Apollo programme.

ISRO

ISROProf Vandawale and his team were at mission control during Chandrayaan-3.

“They were really exciting times. Sitting in the control room, moving the rover around on the lunar surface – that was really a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” says Prof Vadawale.

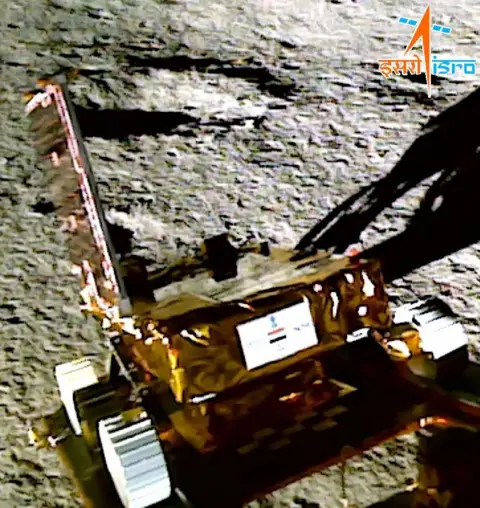

When India’s lander, called Vikram, made its celebrated soft landing on the south pole last August, a rover called Pragyaan drove out of the craft.

Pragyaan rambled around the lunar surface for 10 days, while Prof Vadawale and his colleagues worked around the clock instructing it to collect data at 70 degree south latitude.

The robot was built to withstand swings of temperature between 70C and -10C, and could make its own decisions about how to navigate the uneven and dusty lunar surface.

It took 23 measurements with an instrument called an alpha particle X-ray spectrometer. This basically excites atoms and analyses the energy produced in order to identify the minerals in the Moon’s soil.

The team of scientists also found evidence of a huge meteorite crash in the region four billion years ago.

The crash is thought to have made the South Pole–Aitken basin, which is one of the largest craters in the solar system, measuring 2,500 km across.

It is about 350km from the site India’s Praygam rover explored.

But the scientists detected magnesium, which they believe was from deep inside the Moon, thrown up from the crash and propelled over the surface.

“This would have been caused by a big impact of an asteroid, throwing out material from this big basin. In the process, it also excavated a deeper part of the Moon,” said Professor Anil Bhardwaj, director of India’s Physical Research Laboratory.

The findings are just some of the scientific data collected during the Chandrayaan-3 mission which eventually hopes to discover ice water on the South Pole.

That discovery would be a game-changer for space agencies’ dreams of building a human base on the Moon.

India plans to launch another mission to the Moon in 2025 or 2026 when it hopes to collect and bring back to Earth samples from the lunar surface for analysis.