Former British media executive Will Lewis reportedly offered advice to then–Prime Minister Boris Johnson as a newspaper editor in the UK.

William Lewis, the new CEO and publisher of the Washington Post Company, speaks to the staff and employees at the headquarters in Washington, DC, in November 2023.

(Marvin Joseph / The Washington Post)

For much of his five-month tenure as publisher of The Washington Post, former Murdoch tabloid impresario Will Lewis has been plunged into the seamy saga of his Fleet Street past—chiefly the role he played, during his tenure at The Telegraph, in Britain’s long-running phone-hacking scandal. Now a new report from The Guardian suggests that Lewis’s unseemly exploits went further than that: He also allegedly turned the same sleazy skill set to the political advantage of his longtime crony in the corridors of Tory power, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. After Lewis had wound up his tenure as publisher of the Murdoch prestige property The Wall Street Journal, he settled into a role as an informal adviser to Johnson’s government, helping to steer a consortium of flacks dedicated to saving Johnson’s comically scandal-ridden premiership. Lewis and his colleagues worked under a code name seemingly lifted from an Armando Iannucci production: Operation Save Big Dog.

Guardian reporters Stephanie Kirchgaessner and Anna Isaac cite three unnamed sources close to Johnson’s government who say that Lewis told Johnson officials to scrub their digital communications in the wake of the disclosure that Johnson and his inner circle had defied Covid lockdown restrictions by drinking and partying in luxe venues. The scandal badly damaged Johnson’s already flailing government, and Lewis reportedly sought to stanch the bleeding by personally urging staffers to disappear WhatsApp and text messages pertaining to the episode—advice that contradicted a December 2021 e-mail directive from Johnson officials to save all such communications as a civil service investigation proceeded. Representatives for both Lewis and Johnson denied these claims to The Guardian.

As well they might. It’s a poor look for the successor of Katharine Graham—the former Post publisher who defied the strong-arm press-suppression tactics of the Nixon White House during the Pentagon Papers and Watergate scandals—to be purportedly engineering a cover-up on behalf of a publicly humiliated political leader. Yet such overtures appear to be second nature to Lewis, who previously arranged for Johnson to assume a cushy sinecure as a columnist at The Telegraph in 2008—a gig that paid £250,000 a year, or more than 100,000 quid more than Johnson pulled down at his then–day job as mayor of London.

Lewis’s stomach-baring antics at the Big Dog’s behest, should they be corroborated, would also badly discredit the alibi of first resort for his other misconduct: that he strayed into sketchy practices during his apprenticeship as a Fleet Street reporter, but later matriculated into executive maturity, and corrected the error of his ways.

That feeble excuse was already overstrained by Lewis’s alleged role in the UK press’s phone-hacking scandal, as both a working journalist and a news executive. It was, indeed, a London court’s recent decision in a pending phone-hacking suit that cleared the way for plaintiffs’ claim that Lewis, during his tenure as a London Murdoch executive, sought to delete millions of e-mails documenting the scandal. In a heated conversation with since-departed Post Executive Editor Sally Buzbee, Lewis told her that the court decision didn’t warrant coverage. (NPR media reporter David Folfenflik, meanwhile, separately disclosed that Lewis dangled an exclusive profile before him—on the condition that he, too, refrain from mentioning the phone-hacking suit.) Lewis denies that his exchange with Buzbee amounted to improper business-side intrusion into news coverage at the Post, or played any role in Buzbee’s abrupt departure.

Yet laid alongside the new Johnson revelations—and Lewis’s near-identical pro forma denials there—the phone-hacking saga underlines a clear pattern in Lewis’s career, and it has very little to do with the practice of journalism. The fallout from the decade-long phone-hacking scandal has exposed, in excruciating detail, the lengths to which the Fleet Street cartel goes to promote clicky titillation for the sake of clicky titillation.

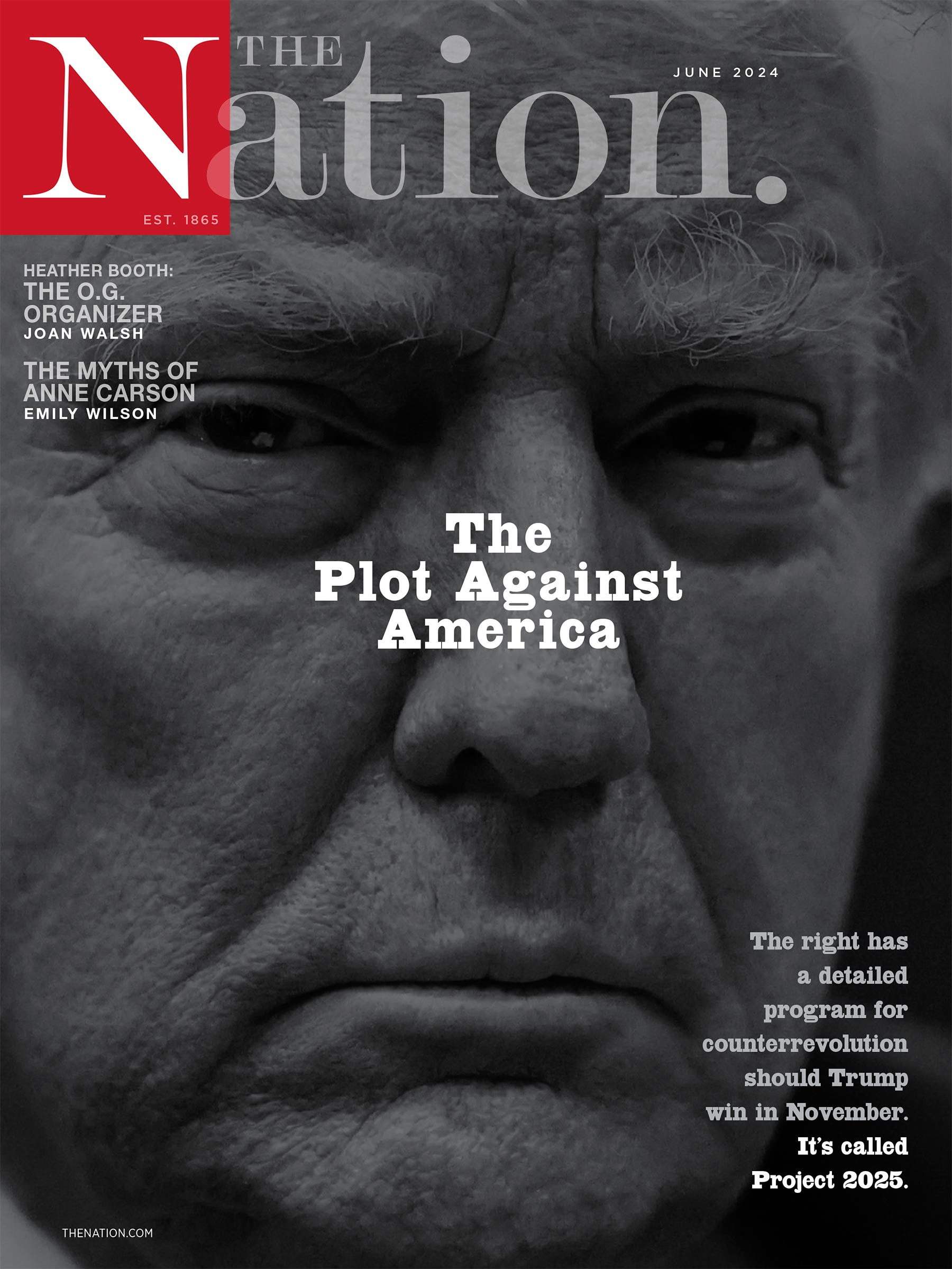

Current Issue

British law permits news outlets to bend legal restraints when they are pursuing stories that clearly advance the public interest. That is pretty clearly the case in the story that Lewis helped obtain for a fee when he was at The Telegraph—a breakdown of bogus expense reports and housing claims lodged by members of Parliament. But the entirety of the phone-hacking operation sought embarrassing revelations about celebrities, including Prince Harry, and salacious information about non-public figures such as murder victims—and crucially, some officials allege, harvested kompromat-style information about their private lives to be used as de facto corporate blackmail to advance the interests of Murdoch’s news empire.

In other instances on Lewis’s watch, The Telegraph used a private investigator (known in British journalism circles as a “blagger”) to tease out information from sources via deceptive means, including a report about boardroom wrangling at the Manchester United soccer club, and a dispatch by Lewis’s protégé Robert Winnett—who’d been tapped to assume the editorship of the Post in a year—about 60 millionaires jockeying to purchase a new high-end Mercedes-Benz model, the Daimler. (In the wake of all these disclosures, Winnett has now declined the Post editorship, which can only be a bad sign for Lewis’s longer-term prospects at the paper.) Science has yet to develop magnifying glasses strong enough to detect the public-interest benefits of documenting the luxury vehicle-coveting mores of the ultrarich—though Winnett did gamely try to summon one by dubbing the car in question “the Nazis’ favorite limousine.”

The accounts of Lewis’s growing résumé of misconduct and malfeasance have so far hinged on the supposedly divergent “cultures” of British and American newsgathering—misleadingly so, as UK journalist James Ball argues. In reality, what’s damning about Lewis’s shady managerial track record is the same malady that afflicts journalism across the world today: an inert ethos of corrupt, celebrity-fueled gotcha-ism, endlessly repurposing content-starved gossip and innuendo as though it’s history-making discourse on the order of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. This is the uncritical mindset that first elevated Donald Trump to public attention—and continues to confer legitimacy to a rising fascist movement on brain-dead autopilot. It’s the same posture of inert institutional deference before power that’s authored the overlapping crises of legitimacy in the political, legal, corporate, and media worlds. What the Lewis saga affords is a close-in glimpse of just how supremely counter-journalistic such undertakings prove to be in practice; in both the Johnson and phone-hacking cases, Lewis is charged with strategically suppressing damning information in order to please his corporate paymasters and ideological cronies. So much, in other words, for telling the truth without fear or favor.

As my colleague Jeet Heer has suggested, this eager solicitude before power could well be why Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos tapped Lewis for the publisher’s job in the first place. Bezos—who, in his tour as owner of the monopoly consumer leviathan Amazon, used to refer to his competitors as “gazelles” whose carcasses were targeted for vicious predation by his retinue of market-conquering cheetahs—may well look at Murdoch’s sleazy antidemocratic empire and think, “I want one of those, too.” If so, his eager quisling Will Lewis is already hitting all the right notes; in dismissing the reporting of Folkenflik about Lewis’s pay-to-play profile offer, he derisively referred to the NPR correspondent as “an activist, not a journalist.” As the long-suffering readership of the Post knows by now, that’s what the stooges in the C-suites always say.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation