Books & the Arts

/

January 24, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson and the battle over American history.

One interpretation presents the country as irredeemably tainted by its past. Another contends that the United States has also tended toward egalitarianism.

In the fall of 2019, during Donald Trump’s first impeachment hearing, a historian of 19th-century America by the name of Heather Cox Richardson began to publish essays summarizing the day’s political news on her Facebook page. Her calm, clear, and matter-of-fact voice offered readers a daily digest that managed to sidestep the shrill hysteria of Twitter and the confusing blow-by-blow of press accounts. As she continued herreadings of current events, she discovered that there was a tremendous market for just such an approach.

Books in review

Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America

Buy this book

Over the dramatic course of 2020 and 2021—from Covid to the election to the events of January 6—Richardson’s straightforward analysis won her a vast readership. She soon began to publish her reports as a Substack newsletter under the title Letters From an American, borrowed from the famous Revolutionary-era rhapsodies of Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, whose Letters From an American Farmer offered a plainspoken celebration of American democracy. The newsletter went on to amass one of Substack’s largest audiences. With about 1.3 million people reading each missive, Richardson had become a true history star.

Richardson’s popularity is notable in itself. Many of the historians of earlier generations who rose to popular acclaim have been august personages, usually male, declaiming from on high. Richardson, by contrast, is a woman; her voice is sincere, humble, approachable, and jargon-free. She knows a lot about American history, but she doesn’t club you over the head either with her mastery of scholarly arcana or her ironic hot takes.

Richardson’s distinctive persona and gentle egalitarianism are at the center of her new book, Democracy Awakening. She draws on her scholarly background as a historian of the Republican Party of the 1850s to make her case. Asserting that the party under Trump is committed to a radical vision of economic, racial, and social hierarchy, she argues that this is part of a much longer history, one that goes back to the 19th century and the years that preceded the Civil War. In that era, the Southern economic elite, whose wealth relied on extreme exploitation and racial subordination, sought to impose its vision that “some people are better than others” on the American populace, capturing such institutions as the Senate and the Supreme Court in order to uphold its minoritarian views. One interpretation of American history today presents the country as irredeemably tainted by its past, a sordid history of racism, slavery, and violent conquest. Richardson contends that this is only part of the story and that the “fundamental principles” of the nation have tended toward egalitarianism; often, however, it has been up to marginalized groups—women, Indigenous people, and especially Black Americans—to remind the rest of the country of its creed. In this way, Democracy Awakening is worth reading not only for its own merits but also for what it tells us about its readers and how an important swath of the public understands our contemporary dilemmas.

Democracy Awakening is organized into three parts. The first looks at the history of the contemporary right, which Richardson argues began as a mobilization against the New Deal. (“Today’s crisis began in the 1930s,” she writes.) For Richardson, the word “conservative” is inadequate to describe this right-wing mobilization, because it has almost always been committed to making radical changes in American institutions to achieve its goals. Quoting Abraham Lincoln’s February 27, 1860, speech at Cooper Union in New York City, she endorses his idea that the enslavers were the revolutionary, destructive radicals, who sought to entrench slavery in the United States with a commitment that far outstripped that of the founders. The party of Lincoln, she writes, “put into practice [its] conservative position that the nation must, at long last, embrace the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence: that all men are created equal and must have equal access to resources to enable them to work hard and rise.”

Current Issue

The New Deal, Richardson argues, also embodied these principles, and thus the forces that resisted it in the 1930s and ’40s were not “true American conservatives,” but instead “the same dangerous radicals Lincoln and the Republicans of his era warned against.” Likewise, the common people who fought in the armed forces during the Second World War and who later joined the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s were the true defenders of democracy, while the “conservative” heroes who wrapped themselves in the trappings of Americanism were the ones resisting the country’s democratic promise and, as a result, laying the foundations for our current authoritarian threat.

After exploring the roots of the American right in the 1930s and ’40s, Democracy Awakening moves on to the present. The second section of the book covers the bewildering cascade of events during the Trump years: Russiagate, Charlottesville, the first impeachment, Covid, the election interference in 2020, and finally January 6. Underlying these twists and turns, Richardson argues, was a broader pattern found throughout the history of the American right—a power grab analogous to that of the enslavers in the years before the Civil War. The reliance of the Republican Party today on the courts suggests, to her, a parallel with the antebellum era: “Like today’s Republicans, as southern enslavers lost support, they entrenched themselves in the states, then took over the machinery of the federal government and then the Supreme Court.” The goals of the Republican Party today are an extension of those earlier ones, she writes. “The MAGA Republicans appeared to be on track to accomplish what the Confederates could not: the rejection of the Declaration of Independence and its replacement with the hierarchical vision of the Confederates.”

From our Trumpian present, Richardson then goes back to the founding era, discussing the American Revolution and the ratification of the Constitution. Her return to the past is intentional: She wants to show that the hierarchical vision of American history avowed by the right has always had its adherents—the loyalists, the slaveholders, the industrialists—but also that this vision has generally been contested and has often represented a minority of the country.

Yes, there were many in the American colonies who were true believers in the monarchy and wanted to remain part of the British Empire, but they eventually gave in to popular calls for revolution and independence. The founding fathers drafted a constitution that legitimated treating human beings as property, but they also wrote a document that was capable of amendment. By the 1850s, the slaveholders were defending states’ rights as an alternative to government by the national majority, seeking to silence abolitionists by violence if need be. Yet “these defenders of human enslavement” constituted a “small minority of the country” and had to resort to these undemocratic measures precisely because they knew they were losing the political war. The Republican Party under Lincoln and William Seward presented itself as resisting a “slave power” that had perverted the real ideals of the nation.

In this context, the Civil War and Reconstruction were, Richardson argues, truly moments of a “new birth of freedom,” a second founding based on national birthright citizenship. The labor movement of the late 19th century took up these ideals as well. Wealthy white men sought to “restrict suffrage rights”; the extent to which they would go to achieve this disfranchisement was on display in the bloody labor conflicts of the Gilded Age. Meanwhile, Richardson asserts, “Black Americans, people of color, women, and workers had never lost sight of the Declaration of Independence.” She says little about the Progressive Era and its elite-driven reforms, or about Jim Crow in the South, but instead moves quickly to New Deal and its political coalition, which joined Black and white working-class people—a true majority that would be undone by latter-day Confederates and their ilk, who had no commitment to any democratic or egalitarian ideals.

Richardson’s account bears the weight of the intense debates in recent years over how to teach and commemorate American history. Historians have been divided, roughly, into two camps. On the one side, there are those who are committed to revealing the conquest, violence, racism, and ecological exploitation that haunt every apparent accomplishment of the United States; on the other, there are those who insist that regardless of its flaws, the United States remains a noble experiment in self-government and constitutional order. This argument over national symbols and myths is often presented in stark and simple terms. Was the United States born in a glorious revolution in 1776—or was its birth really in 1619, when the first enslaved African people arrived in Virginia? Is the United States a democratic nation that embodies the best hopes and aspirations of a free humanity—or is it, at its heart, a country born out of a war to exterminate the Indigenous inhabitants of the continent? How can we think and speak honestly about the bleak history of the country while also salvaging what seems redeemable within it—assuming anything really is?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Richardson is aware of these conflicts, and by arguing that egalitarianism is the authentic creed of the country, she does align herself with one side more than the other. But she also wants to find a way to bring these two narratives together: to keep the ideals of American democracy and egalitarianism but to change the heroes. In her telling, the very people who have been most excluded throughout American history are the ones who have most forcefully advanced its central ideas and principles. Yet the ideas and principles are still there, a promise and a beacon to be taken up by those who were not included under them at the start.

In certain ways, Richardson’s account resembles that of Howard Zinn, another great popularizer of American history. But her insistence—echoing that of the pre–Civil War Republicans—that the champions of democracy are the conservative force in American society, while the “slave power” and its later manifestations are a radical force bent on transforming American institutions, means that she has little to say about the leading figures in Zinn’s account, namely the radical activists whose work and utopian vision were necessary to press the United States toward greater democracy. There are very few of these actors in Richardson’s book. While we hear a lot about Lincoln and the Republicans in the 1850s and ’60s and Franklin Roosevelt and the Democrats in the 1930s and ’40s, we hear little about the abolitionists, the socialists, or the Industrial Workers of the World, and certainly not the Communist Party of the 1930s—which, with its slogan “Communism is 20th-century Americanism” and its embrace of the iconography of Thomas Paine and Abraham Lincoln—also sought to claim the mantle of democracy. The New Left, Black Power, the radical feminist and gay and lesbian activists of the 1960s are barely mentioned; Richardson says little about the various anti-war movements as well, either in the 1960s or at other points. The people who pressed for radical change in American politics are portrayed as being, on some level, in its mainstream all along.

Richardson also seems to elide some of the divisions among those seeking to keep the United States true to its founding principles. Hasn’t there always been more disagreement between radicals and reformers over democratic ideals and egalitarian politics than the account of American democracy strangled by an undemocratic elite might suggest? After all, what galvanized the North before the Civil War was not so much abolitionism alone or an egalitarian politics, but the more modest desire to exclude slavery from the West. And while the politics of race and slavery shifted profoundly over the course of the war, at the outset many in the North were far from confident that the war would—or even should—lead to the end of slavery.

When we look at politics today, those opposing Trumpism are also divided about their ultimate political goals. Some liberals frame Trumpism as an illicit power grab that marks a break from the country’s historical commitment to liberal and democratic norms, and so the solution is to defeat Trump decisively at the ballot box and restore order under right-thinking Democrats. But others argue that to truly rout the macho nationalism and reactionary politics of today’s Trump-leaning right requires something more radical than a simple reassertion of civility. Trumpism is not just a program foisted on the country by a malign elite. It has real roots within American political culture and is a response to the dispossession created by the capitalism of the last 40 years, and so it requires a transformative response in kind.

Perhaps another way to understand the problem would be to acknowledge that there have been long-intertwined traditions in American politics not only on the right but among liberals too. One of these traditions has been fiercely egalitarian, as Richardson observes, but another has been deeply discomfited by claims to equality. We are familiar today with the many attempts to justify a vastly unequal society—from invocations of economic competition and the meritocratic ideal to the idea that absent hierarchy, social disorder will result. Given how prevalent those arguments are today, it is heartening to remember that they are not the only ones. The farmer who inspired the title of Richardson’s newsletter had a very different understanding of America—one in which the economic success of one was intimately linked to the success of all, and individual wealth was part of a project of communal prosperity. As de Crèvecoeur wrote: “Here are no aristocratical families, no courts, no kings, no bishops, no ecclesiastical dominion, no invisible power giving to a few a very visible one; no great manufacturers employing thousands, no great refinements of luxury.” He went on to project the utopian ideal: “We have no princes, for whom we toil, starve, and bleed: we are the most perfect society now existing in the world.” But even when Crèvecoeur wrote this, his egalitarian vision was not the only or even the prevailing one, and today its radicalism stands out far more than Richardson’s account suggests.

-

Submit a correction

-

Reprints & permissions

More from The Nation

We all have doppelgängers, and we now know Colin Kaepernick’s is Aaron Rodgers.

Dave Zirin

Israel is trying to snuff out journalism in Gaza. This should be a sound-the-alarm, all-hands-on-deck moment for anyone who professes to support reporters and the work that they d…

Jack Mirkinson

It may seem like there’s little to cheer, but these leaders and activists can show us how to keep fighting the good fight in what promises to be a challenging 2024.

Feature

/

John Nichols

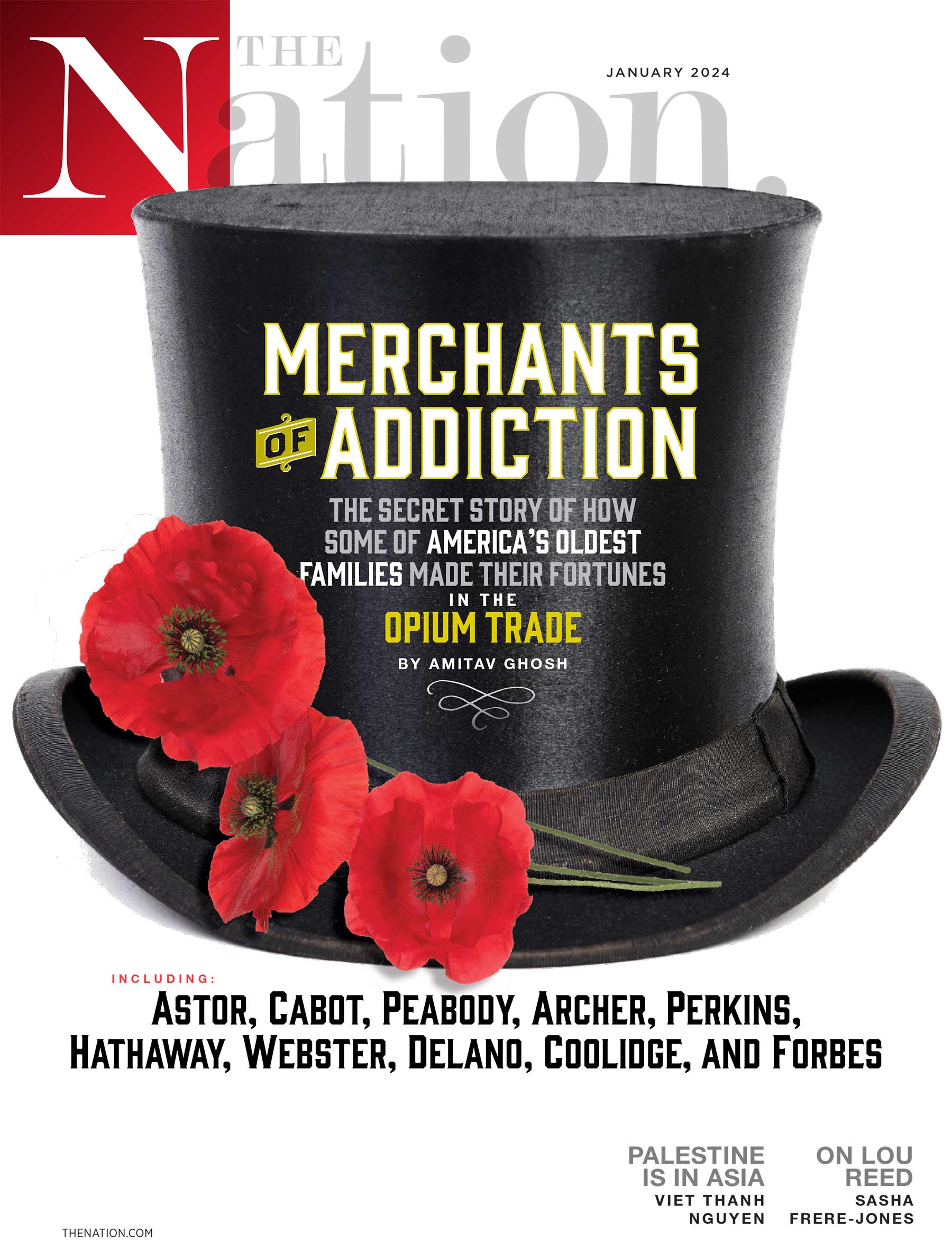

Long before the Sacklers appeared on the scene, families like the Astors, the Peabodys, and the Delanos cemented their upper-crust status through the global trade in opium.

Feature

/

Amitav Ghosh

A new podcast takes us back to the early days of the HIV and AIDS crisis, when a mystery virus began spreading among poor Black and brown communities.

Editorial

/

The Nation