Sheinbaum’s landslide victory is thanks to her commitment to continue policies that put the interests of the working class first.

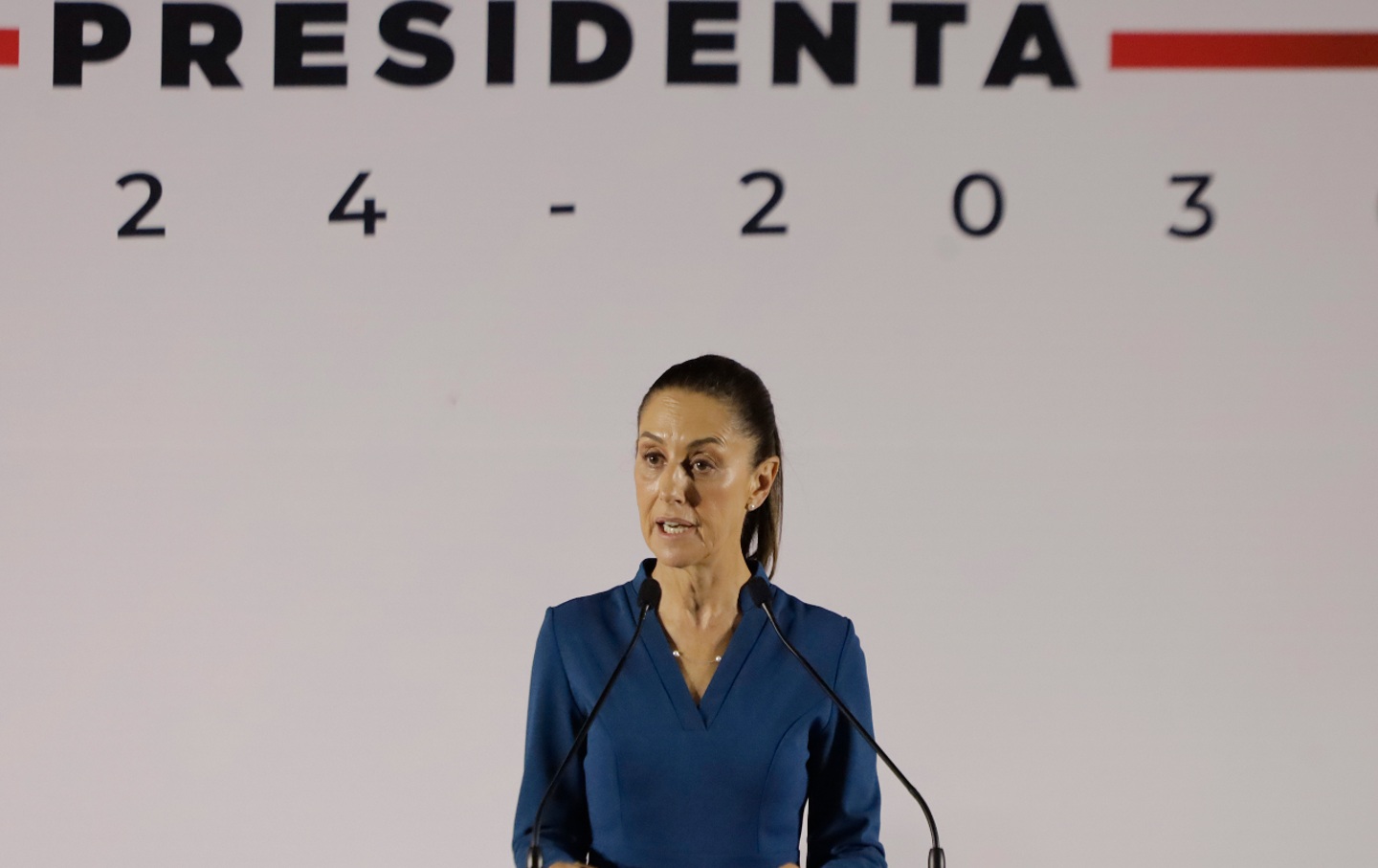

Mexican voters gave an undisputable mandate to Claudia Sheinbaum in that country’s recent presidential election. The final count for the June 2 poll determined that Sheinbaum received 35,923,996 votes, or approximately 59.75 percent of the vote—the highest vote percentage in Mexico’s democratic history. Besting her conservative rival by a 2:1 margin—and with voters rewarding Morena, the leftist party founded by outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, with a strengthened mandate—Sheinbaum is now set to make history, becoming Mexico’s first woman president.

The results in Mexico stand in stark contrast to results in the European Union parliamentary election that saw right-wing and far-right political forces rise at the expense of centrist and leftist parties. Leftist parties that only a few years ago rode a wave of anti-austerity anger now face a credibility crisis after failing to deliver results for working-class people, opening the path for right-wing and far-right parties to make major inroads and capitalize on that discontent. In France and Germany, ultranationalist parties mobilized dissatisfaction and xenophobic attitudes within their populations to deliver a strong message to the leaders of Europe’s pro-austerity mainstream parties.

Meanwhile, the extraordinary showing by the left in Mexico means that the coalition led by Morena will wield a supermajority in the lower house of Congress, easing the path for the party to pursue constitutional reforms. Likewise, the Morena-led coalition is just two seats shy of a supermajority in the Senate as well, even though the upper house’s byzantine system is structurally predisposed to avoid granting any one coalition that level of dominance. The ruling party is expected to easily secure the missing votes in the upper house through negotiations.

The extraordinary result likely exceeded even the Morena party leadership’s expectations. Last year after the opposition and later the Supreme Court frustrated López Obrador’s efforts to reform the country’s electoral authority, the Mexican president floated the possibility of securing a supermajority in the next election in order to give Morena and its allies the freedom to pursue constitutional changes without the need to negotiate with opposition parties.

With Sheinbaum enjoying a 20-point lead in polls, the idea of winning a supermajority seemed more like an effort to mobilize Morena’s political base and mitigate the potential for overconfidence and a low turnout. Mexican voters, however, embraced the call.

AMLO, as the president is known, frequently comments that the Mexican population is the most politicized in the world. It would be correct to conclude that Sunday’s election results are a reflection of that politicization.

Current Issue

The López Obrador government has dramatically raised the standard of living for the working class of Mexico. After being virtually frozen for years, the minimum wage has doubled in real terms during his administration. He significantly expanded social programs, including a universal pension for seniors, easily his most popular measure. The AMLO government also brought in stipends for students and income support for people with disabilities. Domestic workers now enjoy formal rights and social security, and significant strides have been made to eliminate outsourcing. The Morena-led Congress also passed legislation aimed at simplifying unionization efforts and democratizing existing unions. Statutory vacation days have also doubled.

Infrastructure projects have been focused in the historically marginalized regions of the country, helping drive economic growth. For the first time in history Mexico’s southern states, the poorest in the country, are seeing double the level of growth as compared to the rest of the country. Taken together, these policies have lifted more than 5 million people out of poverty.

While the AMLO government is undoubtedly a multiclass coalition, the Mexican working class is firmly in the driver’s seat, with their interests and that of the poor coming first. As Edwin Ackerman wrote in New Left Review’s “Sidecar,” this has led to the “re-emergence of the working class as a political actor” and has firmly consolidated the working-class vote for Morena.

In a surprise to many, and contrary to the propaganda deployed by pundits sympathetic to the opposition, the centrality of the poor and working class in his campaign did not cost Morena support among the middle class. Sheinbaum received widespread support among all economic classes, even with wealthier sectors, winning a majority or a plurality of support among all groups except bosses and business owners.

Predictably, right-wing pundits have responded to the election with classist conclusions that attribute the result to the government’s direct cash-transfer programs. According to Hector Águilar Camín, voters choose Morena in order to keep their social programs; Camin also called Morena voters “low intensity citizens.” Denise Dresser was ridiculed after she expressed disappointment that voters did not heed her warnings about Morena’s alleged threat to the country’s democracy and lamented that they had “once again placed chains upon themselves after we had taken them off.” Political commentator Carolina Hernández argued on the right-wing Latinus outlet during their election post-mortem that voters are too busy thinking about things other than political checks and balances when they go out to “buy tortillas.”

This sort of contempt for the intelligence of Mexicans does help explain why the opposition’s electoral strategy failed so spectacularly. They were convinced that by playing up the humble origins of their so-called charismatic candidate, right-wing Senator Xóchitl Gálvez, they would be able to win over the working class. Despite having mostly opposed AMLO’s social programs, they found themselves forced to defend them, lest voters punish them if they perceived them as threatening the continuity of these programs.

Instead, they centered their messaging on the alleged dictatorial ambitions of Morena. What they failed to realize is that they were asking the citizenry to defend an abstract idea that consistently failed to deliver on the most basic of its promises. The election of Vicente Fox in the year 2000 and the subsequent end of the Institutional Revolutionary Party’s 71-year rule ultimately translated into few material improvements for Mexico’s working class and poor.

During Mexico’s democratic transition, neoliberalism was the order of the day. Despite parties’ alternating in power, little fundamentally changed. The ideological blinders of the architects and beneficiaries of the neoliberal democratic transition made it impossible for them to understand the political moment that Mexico experienced with AMLO’s election in 2018. Denied the access to power that they were accustomed to, these pundits and intellectuals instead grew resentful. They argued that AMLO had “undermined” Mexican democracy by his “populist” style of governance and that his successor aimed to continue this process.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

The election result showed that their arguments, dutifully taken up by the opposition, were soundly rejected by the country. Mindful of the real and life-changing material improvements brought about by AMLO, voters consciously and intentionally acted on López Obrador’s call for a supermajority, delivering a powerful mandate to Sheinbaum to not only consolidate the “Fourth Transformation” of Mexico but to deepen it.

President López Obrador, President-elect Sheinbaum, and Morena’s leadership in Congress have already announced that a series of wide-ranging reforms that the president says are aimed at restoring the “public, social and humanistic character” of the 1917 Constitution will be discussed this coming September, before the official end of AMLO’s term. Morena has long sought changes in the electoral authority and a reform of the federal judiciary that the president has described as “rotten,” conservative strongholds of Mexico’s ancien régime, are practically inevitable.

Claudia Sheinbaum has a nearly wide-open field in front of her; the limits to her ability to implement what she calls the “second floor” of the transformation are not political. The greatest threats to Sheinbaum’s agenda will likely come from abroad. Financial markets have predictably reacted negatively to her win and Morena’s supermajority.

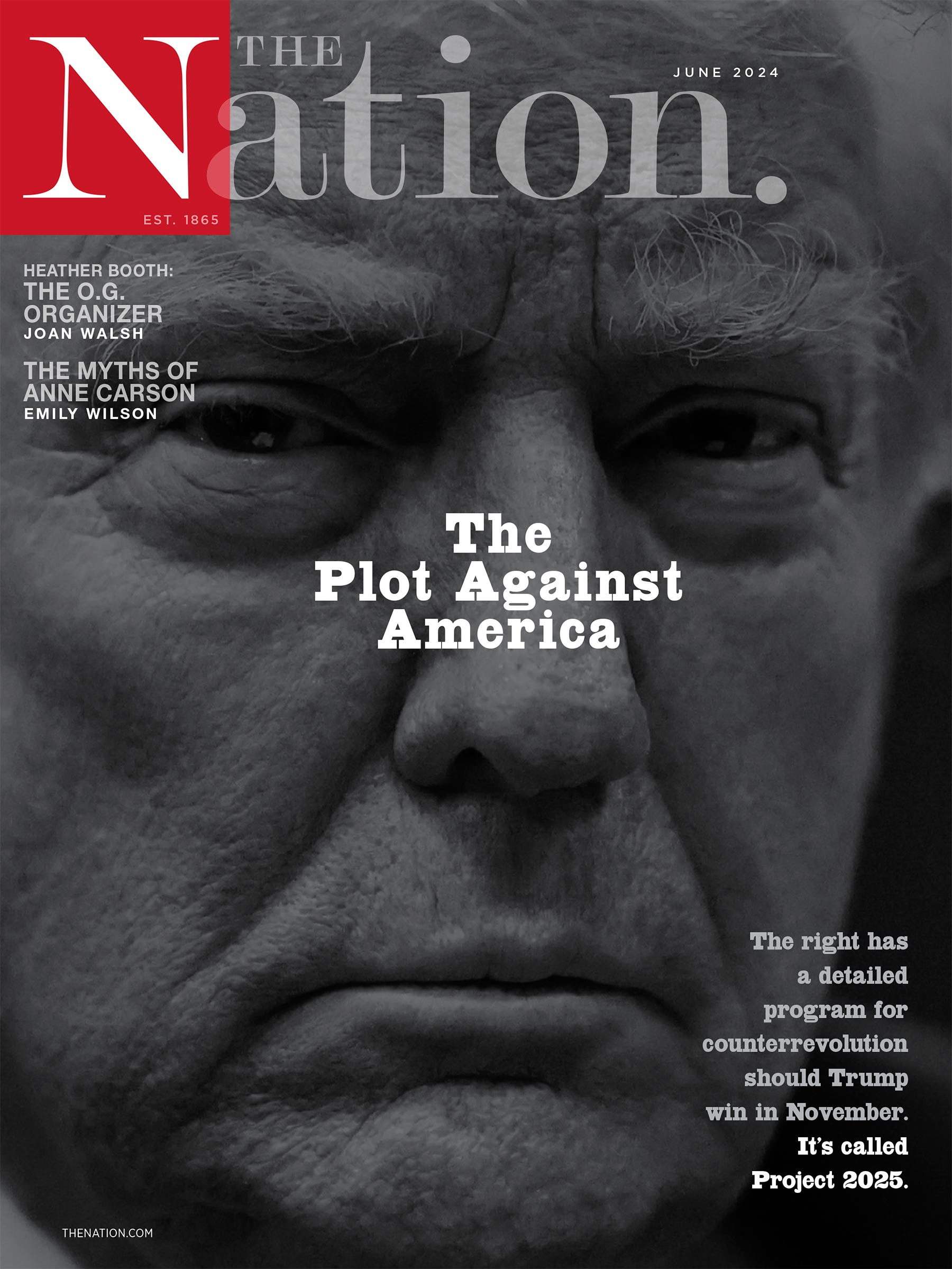

History has shown that after taking a drubbing at the ballot box, right-wing forces in Latin America typically run into the arms of US imperialism. The Mexican opposition will predictably cry to Washington that Mexico is descending into a dictatorship and will call for foreign intervention. The opposition leadership is already trying to sow doubt over the legitimacy of the election, which might politically weaken Sheinbaum’s administration within influential circles in the United States, including among some Republicans who are seriously considering invading Mexico in the event of a Trump victory.

The Sheinbaum government will defend Mexican sovereignty, just as AMLO did before her. But the struggle to defend a pro-worker government in Mexico will also fall in part to US-based anti-imperialist activists.

The Mexican election has shown that when you put the interests of workers first, they will reward you with a strengthened mandate. With US elections around the corner, progressive and leftist forces would do well to study the Mexican experience.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish every day at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Community members embroider the names of some of the journalists killed in Gaza since October 7, public action organized by Rosa Borrás, Puebla, Mexico.

OppArt

/

Rosa Borrás

A reformist challenges five conservatives in the June 28 presidential vote.

Bob Dreyfuss

On the 35th anniversary of the First Congress of People’s Deputies in Moscow.

Nadezhda Azhgikhina

If we’re set on Armageddon, America’s existing force of nuclear submarines is more than enough.

William Astore