The Justice Department is considering allowing Boeing to avoid criminal prosecution for violating the terms of a 2021 settlement related to problems with the company’s 737 Max 8 model that led to two deadly plane crashes in 2018 and 2019, according to people familiar with the discussions.

The department is expected to make a decision on the case by the end of the month. Prosecutors have not made a final call, nor have they ruled out bringing charges against Boeing or negotiating a possible plea deal in which the company admits some culpability, the people said.

It is possible that any negotiated resolution — either in the form of an agreement to defer prosecution or a plea deal in which the company would admit wrongdoing — would include the appointment of an independent monitor to oversee the company’s safety protocols.

Offering Boeing what is known as a deferred prosecution agreement, which is often used to impose monitoring and compliance obligations on businesses accused of financial crimes or corruption, as opposed to trying to convict the company, would avoid the uncertainties of a criminal trial.

But it would anger families of passengers killed in recent crashes who want to see the company pay for its safety lapses. And while prosecutors are considering a new agreement, they recently told the families that they had not ruled out bringing charges, according to a person briefed on the exchange.

Federal prosecutors said in May that Boeing had violated a previous deferred prosecution agreement by failing to set up and maintain a program to detect and prevent violations of U.S. anti-fraud laws. The settlement was reached in 2021, after Boeing admitted in court that two of its employees had misled federal air safety regulators about a part that was at fault in the two crashes.

The aircraft manufacturer’s violation of that settlement allowed the Justice Department to file criminal charges. But some department officials have expressed concern that bringing criminal charges against Boeing would be too legally risky. Officials see the appointment of an independent watchdog as a quicker, more efficient way to ensure that the troubled company improves safety, manufacturing and quality control procedures.

A decision to forgo criminal prosecution would be a win for Boeing and its customers, employees and shareholders, given that such a lawsuit has forced companies to file for bankruptcy in the past.

That includes Arthur Andersen, a once storied U.S. accounting firm that collapsed after being federally convicted of obstruction of justice for its role in the 2001 Enron scandal. Its demise sent ripples through the financial system and serves as a reminder of the devastation a prosecution of Boeing could have on a company that is critical to the U.S. aviation industry.

If Boeing is convicted of a felony fraud, it could be restricted from receiving government contracts — including military ones — which make up a significant portion of its revenue. It would be another blow for a company that has been struggling with significant quality and safety issues, including an episode in January, when a panel on a Boeing 737 Max 9 jet operated by Alaska Airlines blew out in midflight, exposing passengers to the outside air thousands of feet above ground.

The Justice Department has also opened a criminal investigation into Boeing over the Alaska Airlines incident.

The Federal Aviation Administration has faced significant criticism for not exercising enough oversight of Boeing since the Max 8 crashes. The agency failed to ground the 737 Max 8 after the first crash off the coast of Indonesia in 2018, which killed all 189 people on board. Instead, it waited until after a second crash in early 2019 in Ethiopia, which killed 157 people, to finally ground the jets.

Critics of the F.A.A. also have said it relies too heavily on Boeing to conduct its safety work on the government’s behalf. Mike Whitaker, the F.A.A. administrator, said during a Senate hearing this month that the agency had been too hands-off in its oversight of Boeing and that steps were being taken to change that.

The Justice Department’s decision to appoint a federal monitor would send a clear signal that it does not trust the F.A.A. to hold Boeing accountable for the making the safety and quality changes that many have been calling for, said Mark Lindquist, a lawyer for the families of victims of the Max 8 crashes who now represents passengers on the Alaska Airlines flight.

A new deferred prosecution agreement would allow the Justice Department to resolve Boeing’s violation without risking a guilty verdict that could potentially harm one of the country’s most economically important companies.

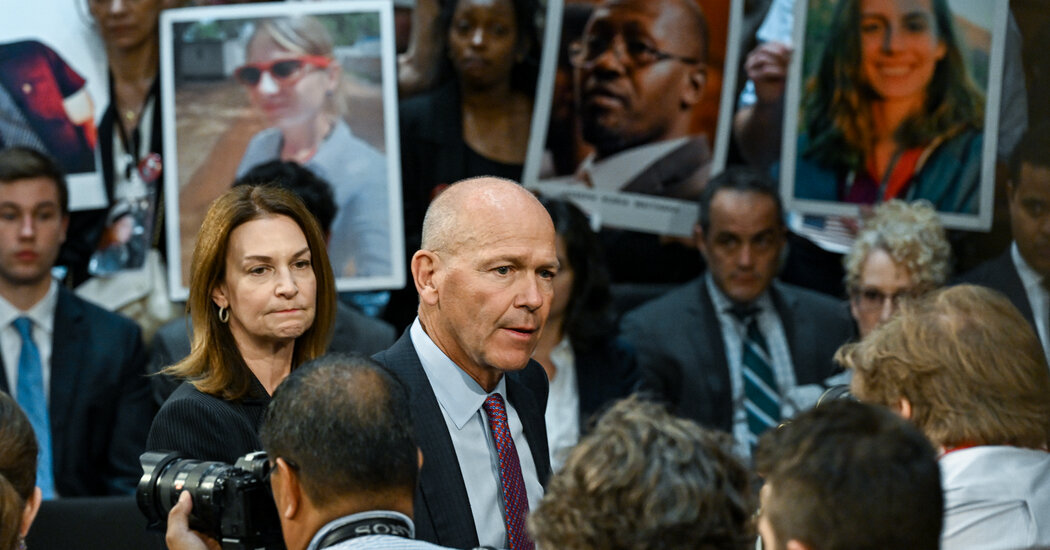

But a decision to not prosecute Boeing over the 2021 settlement violation would be a blow to families of those killed in the Max 8 crashes. Family members of those victims lashed out at Boeing’s chief executive, Dave Calhoun, during a Senate hearing that was convened this week about the company’s efforts to address recent quality and safety lapses. Senators confronted Mr. Calhoun about issues such as forged inspections of critical plane parts and company retaliation against employees who raised safety concerns.

The Justice Department began preparing the families of victims of the Max 8 crashes for the announcement last month, meeting with them for about six hours to update them on the case and to hear their concerns. The families expressed their frustration with the Justice Department for not aggressively pursuing Boeing after the Alaska Airlines episode.

The families told Glenn Leon, the Justice Department’s criminal fraud chief, that they wanted prosecutors to go after Boeing executives. But they were told during the meeting that the department believed a guilty verdict from a jury would be unlikely. The department lost the only criminal case against a person connected to the Max crashes in 2022, when a jury acquitted a former technical pilot for Boeing, Mark A. Forkner, of defrauding two of the company’s customers.

The Justice Department declined to comment.

Mr. Lindquist, the lawyer for the families, said that Justice Department officials had mentioned a deferred prosecution agreement as an option and told the families about the advantages of such an agreement. The department also pointed out the risks of going to trial.

Still, Mr. Lindquist said, the families wanted justice, and another settlement for the company in which it avoided prosecution would not feel like accountability.

“Normally if a criminal defendant received a sweetheart plea bargain and then violated the conditions of the deal, D.O.J. would bring the hammer down hard,” Mr. Lindquist said. “No other criminal defendant would ever receive a second deferred prosecution agreement.”