A spacecraft has launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida to search for signs of alien life on one of Jupiter's icy moons.

NASA launched the spacecraft at 12:06 local time (16:06 GMT) after Hurricane Milton forced the mission to postpone plans last week.

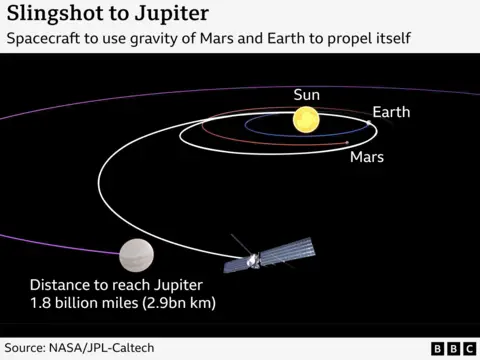

Europa Clipper will now travel 2.8 billion miles to reach Europa, a mysterious moon orbiting Jupiter.

It won't arrive until 2030, but what it discovers could change our understanding of life in the solar system.

There may be a huge ocean beneath the Moon's surface containing twice the amount of water on Earth.

The spacecraft is chasing a European mission that launched last year, but using a space ram, it will overtake it and arrive first.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe moon is five times brighter than ours

The years-long process to launch the Europa Clipper was delayed at the last minute after Hurricane Milton hit Florida this week.

The spacecraft was brought inside for shelter, but after the Cape Canaveral launch pad was inspected for damage, engineers gave the go-ahead for launch at 12:06 local time (16:06 GMT).

“If we discover life this far from the Sun, it would mean that life originated on Earth,” says Mark Fox-Powell, a planetary microbiologist at the Open University.

“This is extremely important because if it happens twice in our solar system, it could mean that life is really common,” he says.

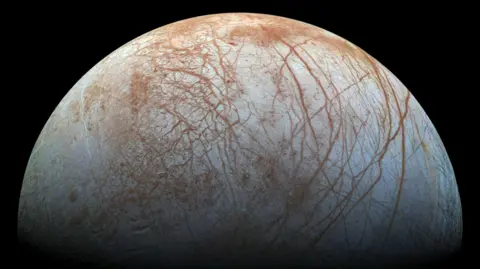

Located 628 million kilometers from Earth, Europa is only slightly larger than our Moon, but that's where the similarity ends.

If it were in our sky, it would shine five times brighter because water ice would reflect much more sunlight.

Its icy crust is up to 25 km thick, and beneath it may be a vast ocean of salty water. There may also be chemicals that are ingredients of simple life.

Scientists first realized that Europa might support life in the 1970s, when they looked through a telescope in Arizona and saw water ice.

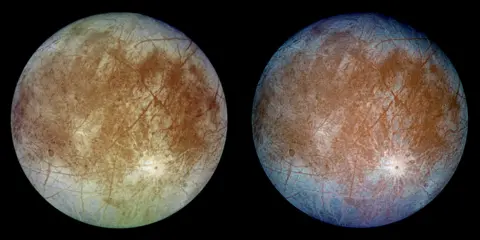

Voyager 1 and 2 took the first close-up images, and then in 1995, NASA's Galileo spacecraft flew past Europa, taking some deeply puzzling photos. They showed the surface dotted with dark, reddish-brown cracks, cracks that may contain salts and sulfur compounds that could support life.

Since then, the Hubble Space Telescope has taken images of what may be a plume of water ejected 100 miles above the lunar surface

But none of these missions got close enough to Europe for long enough to really understand it.

Flying through plumes of water

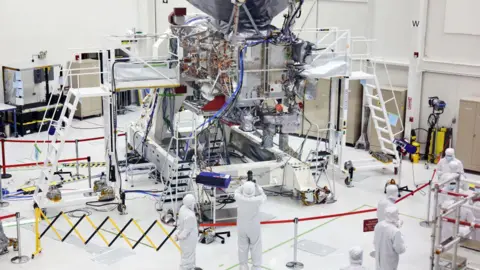

Now scientists hope that instruments on NASA's Clipper spacecraft will map almost the entire moon, as well as collect dust particles and fly through plumes of water.

Britney Schmidt, a professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at Cornell University in the US, helped design the on-board laser that will see through ice.

Institute NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI

Institute NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI“What excites me most is understanding Europe's plumbing. Where is the water? “Europe has an icy version of Earth's subduction zones, magma chambers and tectonics – we will try to look into these regions and map them,” he says.

Her instrument, called Reason, was tested in Antarctica.

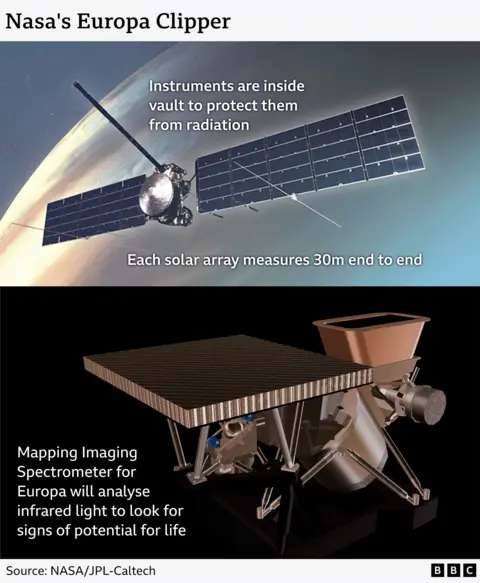

However, unlike Earth, all of Clipper's instruments will be exposed to huge amounts of radiation, which Professor Schmidt says is a “serious problem.”

The spacecraft should fly past Europa about 50 times, and each time it will be blasted by radiation equivalent to a million X-rays.

“Most of the electronics are housed in a vault that is well shielded to protect against radiation,” explains Professor Schmidt.

The spacecraft is the largest spacecraft ever built to visit the planet, and it has a long journey ahead of it. Covering a distance of 2.8 billion miles, it will circle both Earth and Mars before continuing towards Jupiter, a phenomenon called the slingshot effect.

It can't carry enough fuel to spin itself, so it will rely on Earth's momentum and Mars' gravitational pull.

It will overtake JUICE, a European Space Agency spacecraft, which will also visit Europa on its way to another Jupiter moon called Ganeymede.

As Clipper approaches Europe in 2030, it will restart its engines to carefully steer itself into the correct orbit.

NASA/JPL/DLR

NASA/JPL/DLRSpace scientists are very cautious about the chances of discovering life – they are not expected to find creatures or animals similar to humans.

“We are looking for habitability potential, and we need four things – liquid water, a heat source and organic material. Finally, these three ingredients need to be stable for a long enough period of time for something to happen,” explains Michelle Dougherty, professor of space physics at Imperial College London.

They also hope that if they better understand the ice surface, they will know where to land the ship on a future mission.

The odyssey will be supervised by an international team of scientists from NASA, the Jet Propulsion Lab and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab.

At a time when there is a flight into space virtually every week, this mission promises something different, suggests Professor Fox-Powell.

“There is no profit. It's about exploration and curiosity and pushing the boundaries of our knowledge about our place in the universe,” he says.