“The Chicago mayor is the most protested mayor in the entire country,” says Brandon Johnson, the chief executive of the nation’s third-largest city. As a veteran labor activist who has organized his share of demonstrations, Johnson’s good with that. The Nation spoke with the mayor as he prepared for his city to host the 2024 Democratic National Convention, which will see its share of protests and which will feature added intrigue now that President Joe Biden has dropped out of the race and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris to take his place on the ticket. But Johnson has not been fretting about the uncertainties: He remains confident that Chicago will host a great convention. He expects a blend of pomp and protest, and he is looking to spread his vision for progressive governance on everything from raising wages for tipped workers in Chicago to achieving a ceasefire in Gaza. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—John Nichols

BJ: Well, that’s the beauty of this moment, right? You have someone like me who’s deeply tethered to grassroots movements, political organizing, working with faith and labor. Many of the individuals who are applying for permits to protest, I’ve stood alongside. And we’ll have delegates and people coming from all over the world not just to celebrate the leadership of President Biden and Vice President Harris, but also to propel us into the next stretch with some energy, right? So we’re talking about safe and peaceful protests while also having an energetic, vibrant convention.

Chicago is designed for this type of complexity, for moments where these types of contradictions exist. This is the city that said “Yes, we can!” [recalling the 2008 presidential campaign of Chicagoan Barack Obama] and “Keep hope alive!” [recalling the 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns of Chicago’s Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr.]. But it was also the city where Dr. King said [something along the lines of] “Ain’t no place like it.” He had never seen the type of visceral, in-your-face resistance and racism [that he encountered at demonstrations in Chicago]. There were places in the Deep South where you had your sheriffs and you had your dogs, and you had people who were obviously opposed to equal rights for Black folks. For the city of Chicago, that hatred was right on the block. It wasn’t confined to some person who had a powerful political position, whether it was in law enforcement or government or business. This was just everyday people who live on the block, who would be in your face making it very clear: “We don’t want you here.” So that was the city of Chicago, as Dr. King described it, though he also said [paraphrasing his 1966 speech to Chicago community organizations], “You figure it out in Chicago, you can do it anywhere in the world.”

JN: The year 1968 is top of mind for the media, and many top Democrats, because things got wild for the city then. Are you worried there could be chaos again?

BJ: No, because I’m different from the mayor who was around during that time. So there’s a much different approach that I’ll take—again, peaceful, safe, but energetic and vibrant, all at the same time. The First Amendment is not just fundamental to our democracy; Black liberation doesn’t become a possibility or even a reality without the ability to protest the government. And so, for me, we get to show up at the convention and lay out our vision for working people in this city, while hearing from the voices of protesters who want to reach the broad swath of leadership that makes up the Democratic Party.

JN: That’s an important point. Many of the people protesting want the party to do better. It’s not necessarily that they want the party to lose. They want the party to be more of something.

BJ: And if there’s anyone who understands that, it’s a Black man who’s the mayor of the city of Chicago. Wanting the government to do more for people who have been stuffed in the margins for decades—that is our reasonable service.

JN: Let’s talk about one challenge you’ve faced on your City Council, and that was the Gaza vote. You had to break the tie. Tell me about that.

BJ: I thought about how the generation that made it possible for me to become mayor understood Chicago’s role in a global context. Black political leaders were taking a position against South African apartheid; they understood Black liberation from a global [perspective].

[Nearly 40 years ago,] when Mayor Harold Washington declared the city to be a sanctuary, it was in the context of Ronald Reagan’s so-called war on communism and the destabilization of Central and South America. And so that’s the perspective and the mindset that I bring to the fifth floor [of City Hall]: Chicago is a global city, [and] our decisions have ramifications around the world.

So, in October, [the City Council] condemned in the most fierce terms the terrorist attack against the Israeli people. And then, as death [totals in Gaza] became increasingly more horrific, [it was important for us to raise] our voices. Calling for the release of hostages and a ceasefire, for us, is in keeping with our birthright as Chicagoans.

This is part of a long history of progressive Black and brown and white voices who understand their assignment, and that assignment is not confined to building affordable homes in Chicago, providing behavioral health services in Chicago, providing opportunities for young people in Chicago. We also understand that we have to tell the world that it has a moral responsibility and obligation to make sure that we’re protecting people on the West Side of Chicago and in Gaza—that we see liberation and freedom in the same context, whether it’s people who are suffering from abject poverty or those who are suffering from a foreign policy that’s causing death and trauma and terror. So we get to say “Ceasefire!” We get to be the voice of those voices that are not heard, and we get to walk into a very profound, unique tradition as Chicagoans to provide that type of moral clarity for the world.

JN: Let’s talk about how you got elected mayor. You started at 3.2 percent in the polls, yet you won. It’s often said that the Democratic Party must maximize its ability to build coalitions. It’s got to build multiracial, multi-ethnic coalitions around a working-class message—and you did that.

BJ: We did do that. It’s very humbling. But what was so potent was that, although we had a small base when we started, the base already reflected the coalition that we would need to win. So labor was already there, faith was already there, community-based organizations were already there. We already had elected officials on the ground [and a] multicultural, intergenerational base—all of the ingredients for a campaign deeply tethered to our values. When I announced, I did not announce alone. I didn’t initiate until we actually got buy-in and support from the coalition, and then we were able to magnify our values—positions that people were already in agreement with. They just wanted to know that there were people and a person willing to elevate and lift those values, unapologetic, with moral clarity and with the pathway to be able to deliver.

JN: It was a tough race from start to finish, but you seemed to enjoy it.

BJ: The beauty of organizing prior to becoming a candidate is that there’s nothing that someone can say that I have not heard.

One sort of “negative” hit against me was that I was a union member—you know, “Because he worked for the Chicago Teachers Union, there’s no way that he can be independent.” What’s so hypocritical, so asinine, about that particular framing [is that] no one said that when a business leader ran—that this person could not be an objective arbiter and a fiduciary, responsible mayor because they’re too attached to business, corporate interests, policing, right?

The other attack was when they “exposed” the fact that my wife and I were on a payment plan for a water bill. It highlighted the fact that, between my wife and I, we did everything right, working hard, and the ends still don’t always meet at the end of each month—like a lot of working people in Chicago. If it’s not your water bill, it could be a different utility. It could be a car bill, [or] a number of things where you’re just moving things around just to exist in Chicago. And that actually is where my motivation is centered around: the person or the persons who are getting up every single day to make life work for them and their family. All they want is to know that someone is committed to making key investments in their lives, prioritizing them so that their lives can be far more sustainable.

JN: It hasn’t always been that way with mayors of Chicago.

BJ: The people of Chicago have witnessed some of the most horrific forms of governance. You’re talking about anti-business and anti-Black. Think about this for a moment: Imagine a politician saying that the way we’re going to move our city forward is, we’re going to sell off all of our public assets. We’re going to shut down our public accommodations, we’re going to tear people’s pensions apart, and we’re going to give it over to billionaires—and that’s how we’re going to build a better, safer Chicago. Who’s winning on that freaking platform? But that’s what’s been done by previous administrations: closing mental health clinics, shutting down public schools, shutting down public housing, raiding pensions of working people, [and] totally destabilizing our economy in a way where the wealth gap [has] continued to grow.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

JN: You’ve made closing that gap a priority.

BJ: I’m fighting to abolish the subminimum wage so tipped workers get a raise [as they did on July 1]. They’re going to continue to get a raise until they are actually matched with the minimum wage in the city of Chicago, plus their tips. We [also] doubled paid time off for workers, so now we have one of the most substantive, comprehensive paid leave—sick leave—[policies] for 1.1 million workers. We did that within the first six months of my administration.

On hiring our young people, we saw a 20 percent increase last year from the previous administration, and we added an additional $80 million on top of what we did the previous year to hire up to 28,000 young people. And we’re going to continue to work to do that. On policing, I made a commitment to hiring 200 detectives within my first term. We’re going to complete that by the end of this year, and we’re way ahead of the end of the first term. And [my administration has budgeted] a quarter of a billion dollars for the unhoused crisis, $100 million for violence prevention, and a $1.25 billion bond for economic development and housing—the largest such bond in the history of Chicago—to build homes and create economic development on the west and south sides of the city, places that have been marginalized for decades.

JN: You also are building a strikingly diverse administration.

BJ: Right now, 45 percent of my administration is Black. Sixty percent of my administration is made up of women. Twenty-five percent brown. More brown folks in my administration than any other administration in the history of Chicago. It is diverse: Black, brown and white. And so I’m saying that, progressive governance can be responsible with the finances of the city, while also making critical investments and responding to an international global crisis, all at the same time, all in the first year.

JN: And yet you’ll get no credit from Republicans. Republicans have a standard line on cities, and it revolves around claims that they are overwhelmed by crime. That doesn’t fit with the data, though, does it?

BJ: Not even close.… The safest cities in America do one thing: They invest in people. That’s what we’re doing. And to your larger point, the city of Chicago is not even in the top 20 in terms of the most violent cities. In fact, since I’ve been in office, we’ve had two consecutive years of reduction in homicides and shootings, while also making critical investments in the neighborhoods.

There’s [still] a lot of work to be done. We have just this ungodly amount of access to illegal weapons…. The ridiculousness around the Republican Party in particular, of not being willing to have real comprehensive gun control in this country, is just mind-blowing, because these are the same [people] that would want to critique a city like mine when violence does happen. It just shows you how disingenuous they are.

JN: They’re also disingenuous on immigration, particularly people like Texas Governor Greg Abbott who are flying migrants to Chicago.

BJ: What Governor Abbott is doing to our country is one of the most iniquitous acts that I’ve seen in modern political history.

JN: You chose that word very carefully.

BJ: I’m trying to remain, you know, tethered to my faith here and try not to use vulgarity. However, it is shameful what he’s doing. Because, look, let’s not ignore that we have a real issue at the border. What we’ve called for repeatedly is real, comprehensive immigration reform …. and when we see what our bordering states are doing, all we’re saying is just coordinate with us. Let’s figure out how we can come up with a plan that allows us to address this crisis, because it’s a real one.

The fact that Abbott was sending the majority of migrants to me and New York Mayor Eric Adams, it tells you where his heart really is. That is wicked, because these families are dealing with very severe and harsh economic circumstances. And then you have Abbott, who doesn’t want to cooperate with the rest of the country. It’s one of the most petulant acts that I’ve seen as a politician.

JN: You recognize a moral component in these debates?

BJ: I’m governed not just by my ideology but my responsibility to something bigger than myself. The Bible says that your treasure and your heart must be aligned: Wherever your treasure is, your heart’s going to be also. And what I have worked to do is to show that progressive leadership, through the lens of Black liberation theology, shows up not just boldly; it shows up with one of the most powerful forces, and that’s love.

JN: It’s my duty to ask, if you could write the Democratic platform on cities, what would you put in it?

BJ: If I could write the platform, I would say that the Democratic Party has to show real commitment to the five demands that descendants of slaves called for. They said housing, health care, education, transportation, and jobs. I would add environmental justice. The platform [really] should speak to the demands of those who built the nation. And you have to make sure there’s, to President Biden’s credit, the Inflation Reduction Act—it’s very powerful. The platform has to be committed to real public accommodations, to those who do the work and those who rely upon those accommodations.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

A conversation about MAGA’s militancy and the strategies to protect Democracy.

Q&A

/

Laura Flanders

Insecure and contemplating defeat, the former president returns to a familiar script.

Jeet Heer

The GOP has been desperately trying—and failing—to shift the public’s attention onto other issues.

Sasha Abramsky

The president’s foreign policy choices in the Middle East and Ukraine have been disasters. Harris needs to make a decisive break.

Amed Khan

Hey, can we circle back to when many supposedly intelligent people were making one of the most obviously ridiculous political arguments of all time?

Joshua A. Cohen

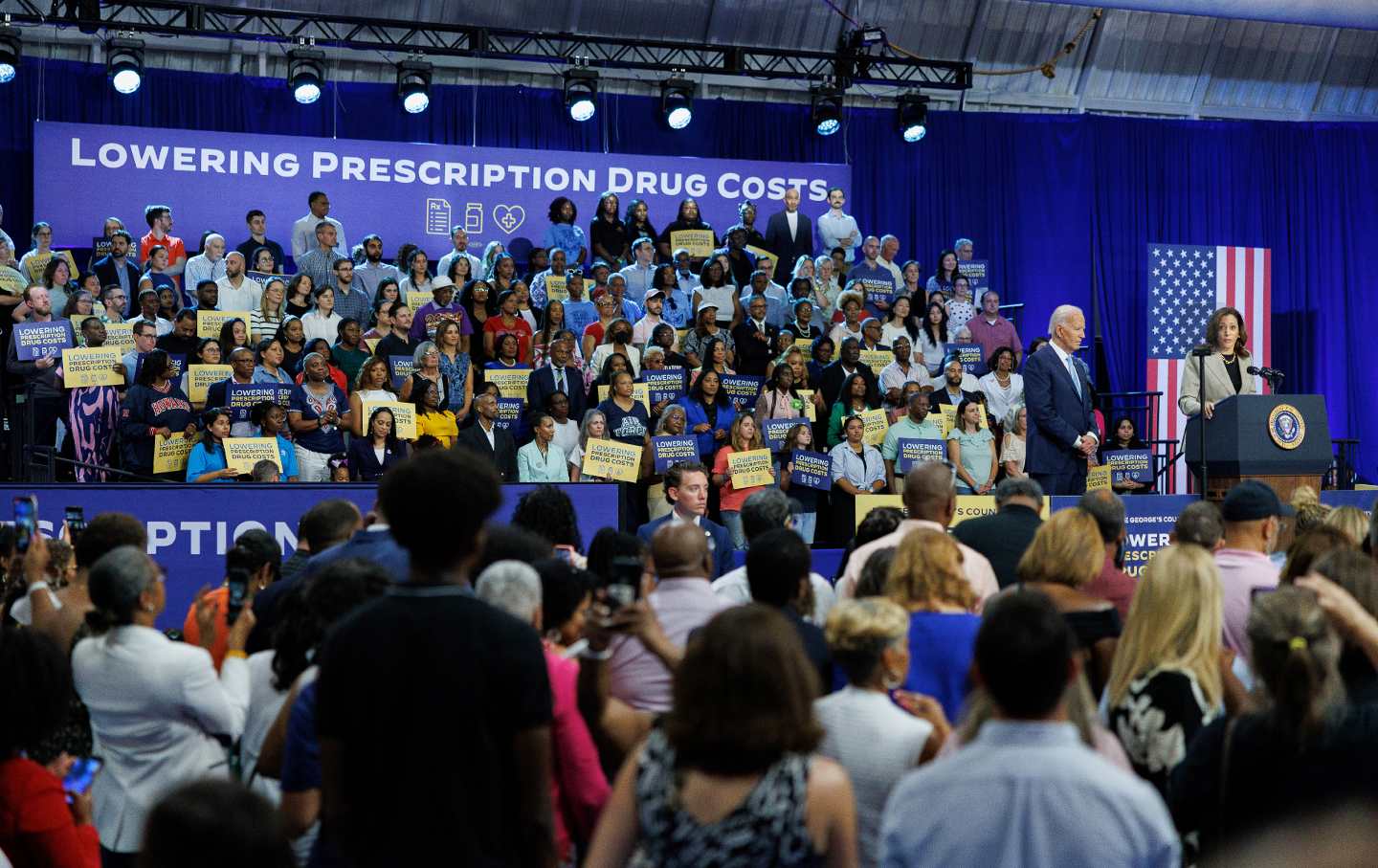

The were celebrating a landmark Medicare price reduction, but they were really putting their partnership back on display.

Joan Walsh