Society

/

August 15, 2024

The Olympic Games supercharge the problems that already exist in a host city. We saw that in Paris—but what will happen in LA?

Fireworks illuminate the sky at the end of the closing ceremony of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games at the Stade de France on August 12, 2024, in Paris, France.

(Mustafa Ciftci / Anadolu via Getty Images)

Paris—At the closing ceremony of the Paris Olympics, outgoing International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach said that the 2024 Summer Games “were sensational Olympic Games from start to finish.” He then added, “Or dare I say: Seine-sational Games.” Bach’s cringeworthy pun was only outmatched by the hyperbole of the Olympic faithful proclaiming Paris to be “the best Olympics ever.” In reality, amid the inspiring, often poetic, feats of athleticism, these Games magnified the social problems of Paris—and the world.

Olympians make the Olympics, and Paris 2024 was no exception. The Paris Games featured athletes who brought exquisite skill and joy to the competition, but they also brought their politics. It started with the opening ceremony, when members of the Algerian team released roses into the Seine to honor those who were shot and drowned in the river by French police in 1961, the final year of Algeria’s war of independence from colonial France. Upwards of 120 people were killed in an incident that, for decades, French officials attempted to cover up. Faïza Zerouala, a French journalist of Algerian descent who writes for Mediapart, told us, “I was very proud they did that. For me, it was proof that Algerian descendants still know who they are” and that “we don’t forget the past,” even if many in France are “blind to its colonial background.” She added, “It was a very important tribute to the martyrs.”

Current Issue

Later in the opening-ceremony procession, one of Palestine’s flag bearers, boxer Waseem Abu Sal, wore a white shirt embroidered with depictions of Israeli fighter jets bombing children in Gaza. He was one of eight Palestinians competing in Paris, including Layla Al-Masri who set a Palestinian national record in the 800-meter run. Fans in Paris celebrated Palestinian athletes wherever they went—even as the press largely ignored them. Few journalists bothered to interview members of the Palestinian Olympic team. The overall absence of attention Palestinian athletes received—the erasure of their struggles—mirrored the war on Gaza and the attendant suffering of deliberately unheard Palestinian civilians.

The competition brought—also underreported—political statements to the playing field. When Manizha Talash, a breakdancer from Afghanistan representing the Refugee Olympic Team, finished her performance, she unveiled a cape reading “Free Afghan Women.” While fans in attendance applauded, as did the athlete from the Netherlands against whom Talash was competing, the Olympic powerbrokers disqualified her. Yes, they disqualified someone from the refugee team for raising awareness about why she is a refugee. By disqualifying Talash, Olympic honchos essentially did the bidding of the Taliban, whose prohibition on women playing sports is precisely why she could not compete under the flag of her home country.

Zerouala also pointed to the importance of Kaylia Nemour, one of France’s top gymnasts, who chose to switch nationalities and compete for Algeria after a protracted dispute with the French gymnastics federation, which was inflexible about where the 17-year-old gymnast trained. Zerouala dubbed Nemour’s gold-medal win on the uneven bars “a colonial reparation.” The victory made Nemour the first African athlete to win a medal in Olympic gymnastics.

While there was no shortage of coverage of women’s boxing gold medalist Imane Khelif, who triumphed despite facing down bigotry and lies about her sex and gender, less was made about her winning gold in France as an Algerian. Khelif’s refusal to speak French in her last press conference, opting for Arabic and English instead, revealed a politics of resistance that Western journalists did not understand.

Politicians often try to exploit the Olympics—and Olympic athletes—for their political careers. But this backfired for French President Emmanuel Macron, whose constant, unrequested hugging of any French Olympian within his five-meter radius was off-putting. After French judoka Romane Dicko won bronze, Macron cupped her head in his hands, an experience that, she said, made her feel “a little embarrassed.” French Olympian Hugo Hay, who qualified for the final in the 5000 meters, even called out Macron for his brazen politicking, declaring, “These are not his Games, but those of the athletes.”

Macron’s tanned visage also evinced a cacophony of jeers when it appeared on the jumbotron at the Olympic fan zone in Place de la Bataille Stalingrad during the gold-medal men’s basketball game between the United States and France. And the Games did not boost his popularity: In early August only 27 percent of the country had confidence in his ability to address France’s problems, only two points higher than in early July.

Amid the media hullabaloo over the Paris Olympics, serious social issues in Paris remain unresolved. To police the Olympics, there were heavily armed security forces from more than 30 different countries, but that is not all. France’s political leaders also transformed the city into their own panopticon, with the French National Assembly greenlighting the use of algorithmic video surveillance. They built this security architecture ostensibly to prevent terrorism, but as is often the case, it was wielded against activists. (There were also heavily armed police units patrolling working-class, immigrant neighborhoods far from the Olympic zone.)

In Paris, we interviewed Noah Farjon, an activist from the counter-Olympics organization Saccage 2024 who was arrested not once but twice, simply for trying to organize informational tours for visiting journalists and concerned locals interested to learn more about the social and environmental effects of the Olympics on Saint Denis, an area to the north of Paris that experienced intensified gentrification because of the Games. These “Toxic Tours,” as Saccage 2024 called them, nabbed the attention of security officials who arrested Farjon and two journalists, detaining them for 10 hours. Days later, Farjon was placed in custody again and fined 135 euros for organizing what police described as an illegal demonstration. After his second arrest, Farjon told us that this “gross police overreach”—approximately 60 police were on hand—“proved their point” about the intensified surveillance of political speech during the Games. Police officers pointed to his previous arrest, when charges were dropped, to justify arresting him a second time, he said. The experience, he told us, “worries me for what’s to come” after the Games.

Off the field, the most under-discussed story were the people in Paris who paid for the Olympics with their shelter and sense of stability. About 12,500 unhoused and precariously housed people were bused out of the city. Making the city “Olympics ready” meant a “social cleansing”—or what activists from Le Revers de la Médaille (The Other Side of the Medal) called nettoyage social. Some were given shelter; others, their whereabouts are unknown. This was an Olympic-size human rights travesty that deserved more coverage.

Now, attention shifts to Los Angeles, host of the 2028 Summer Games. The finale of the Paris 2024 closing ceremony involved a gaudy, star-studded handoff of the torch to LA Mayor Karen Bass. But not even the shine from Snoop Dogg’s golden shoes could blind Kenneth Mejia, LA’s city controller, from the grim realities that differentiate LA from Paris. Mejia posted a graphic comparing the two cities on metrics like transit use and the population of unhoused people. When we consider the massive number of unhoused and precariously housed people in LA—10 times as many as Paris, according to Mejia—one shudders what the “solutions” will entail, especially with California Governor Gavin Newsom waging his war against homeless encampments.

The Olympics are an inequality machine, supercharging all the problems that already exist in the host city. Los Angeles brings Hollywood glitz and glamor but also homelessness, displacement, racialized policing, and a changing environment. If there is one lesson to learn from Paris it is this: Be sober-minded about hosting the Games, don’t drink the Kool-Aid, and definitely do not wait until 2027 to start organizing. There are already activists from NOlympicsLA doing grassroots activism. People should join their efforts to make sure that the most marginalized populations don’t pay the highest price for the next Games.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

AI’s top industrialists say they want regulation—until someone tries to regulate them.

Garrison Lovely

Rural America looms large in the 2024 election. So why is it such a small piece of the Progressive Caucus agenda?

Editorial

/

Anthony Flaccavento

A century ago, labor colleges transformed American unions. It’s time to bring them back.

Feature

/

Daniel Judt

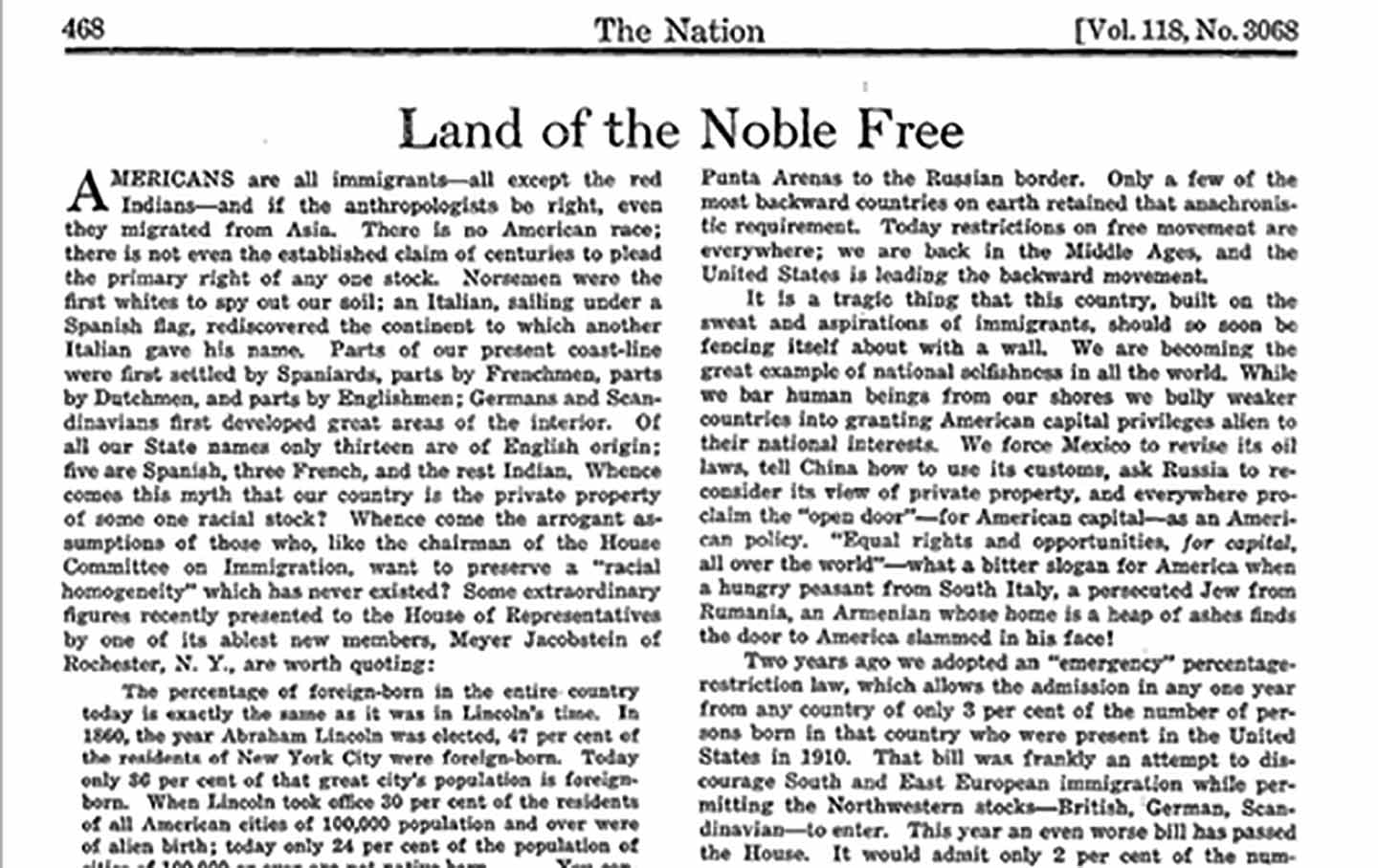

When Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924 a century ago, The Nation issued a prescient warning to its readers.

Editorial

/

Richard Kreitner

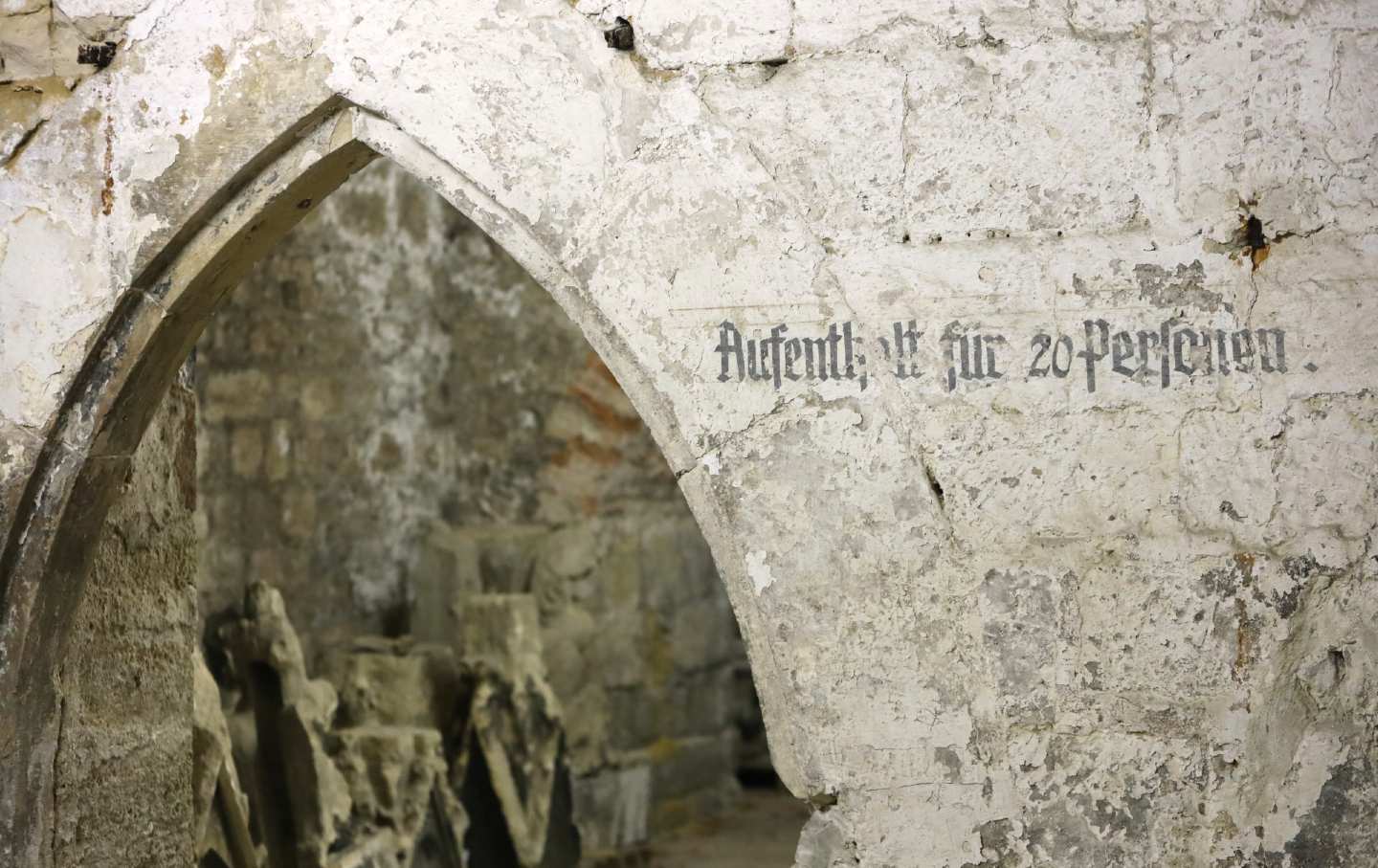

Can a cause still be just, even if atrocities have been committed on its behalf?

Comment

/

Bruce Robbins

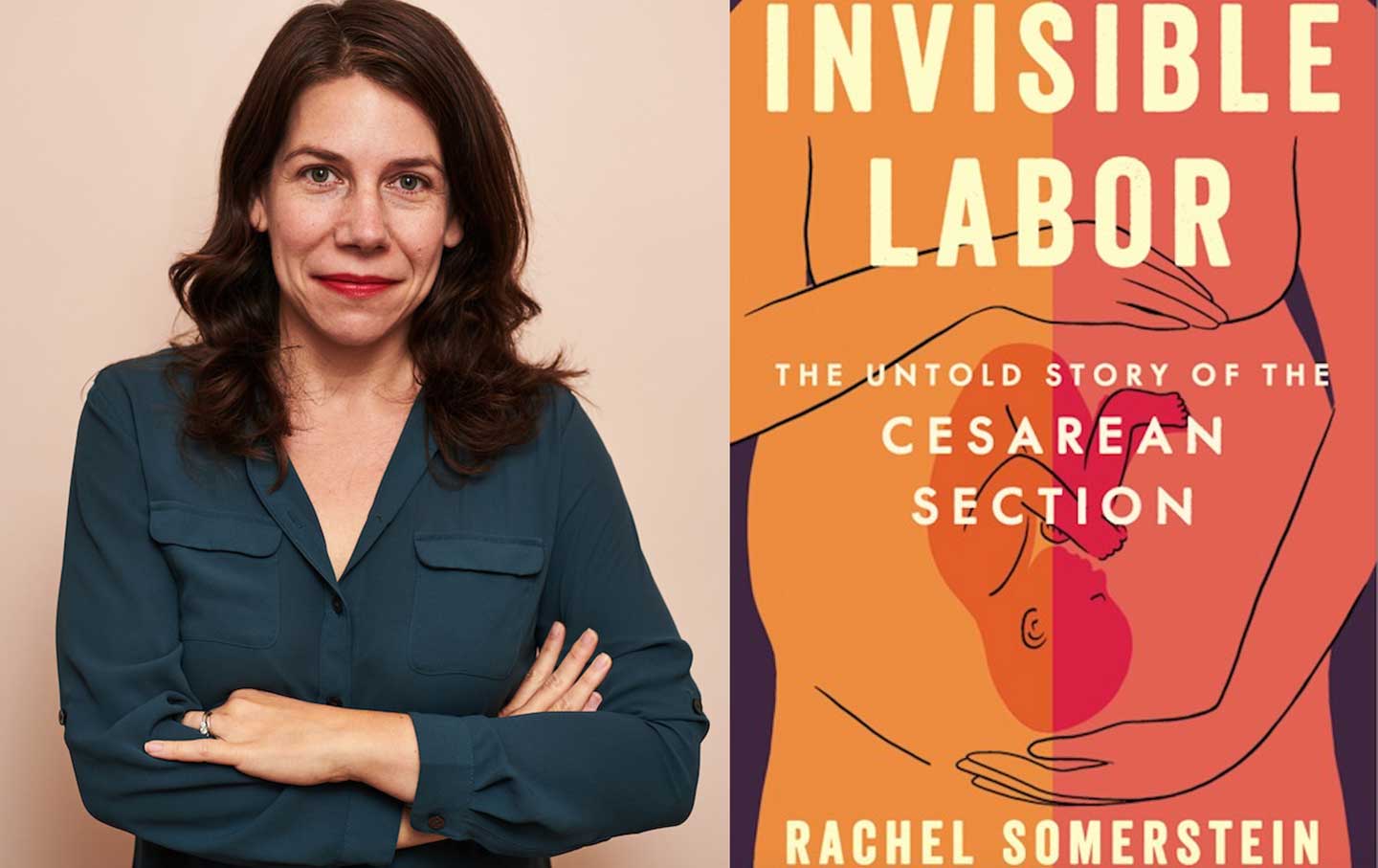

A conversation with Rachel Somerstein about her new book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section.

Q&A

/

Sara Franklin