To be sure, the Republican Party capitulated first. In the 2000s, its small-government-enthralled leadership grew too distant from any social base, too caught up in the concerns of its donors, and too internally fractious to coordinate. It outsourced many of its central functions—like voter mobilization and candidate recruitment—to groups with narrow agendas. It papered over the destruction wrought by its policies with grievance-based, dog whistle politics. Into this empty shell stepped Donald Trump, and he wielded it like a king hermit crab. It is now his party and his alone, with a platform built from his ramblings. It is not a political party capable of sustaining liberal democracy, which depends on the rotation of power and pluralistic compromise.

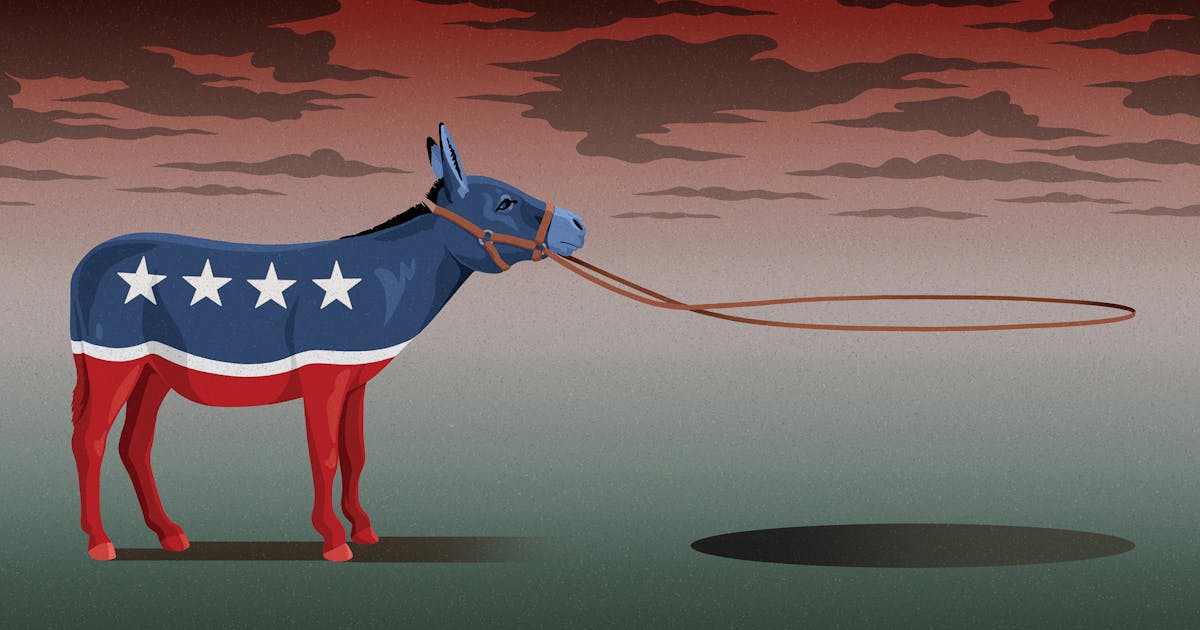

And the Democratic Party? Is it capable of sustaining liberal democracy on its own, or is it, too, on the brink of capitulation? In the latest Gallup poll, just 23 percent of Americans identified themselves as Democrats—the lowest number in the poll’s 90-year history. Meanwhile, 51 percent of Americans choose not to affiliate themselves with either party—the highest share in the history of polling. This level of disaffection suggests that the two parties are failing in their crucial role as intermediary institutions—collectively integrating concerns of diverse Americans into a coherent and meaningful representation. Without parties to integrate, represent, and share power, democracy falls into chaos and authoritarianism, violence and force. There is a simple, obvious answer to our present conundrum: Replace them with new and better parties.

But this is not so easily done. Democrats and Republicans have too long benefited from America’s system of single-winner elections, which ensures that one or the other of them will triumph. They have no incentive to evolve.