Books & the Arts

/

June 27, 2024

Joseph Andras’s novel on the Vietnamese revolutionary’s salad days in Paris imagines how a young radical became an icon.

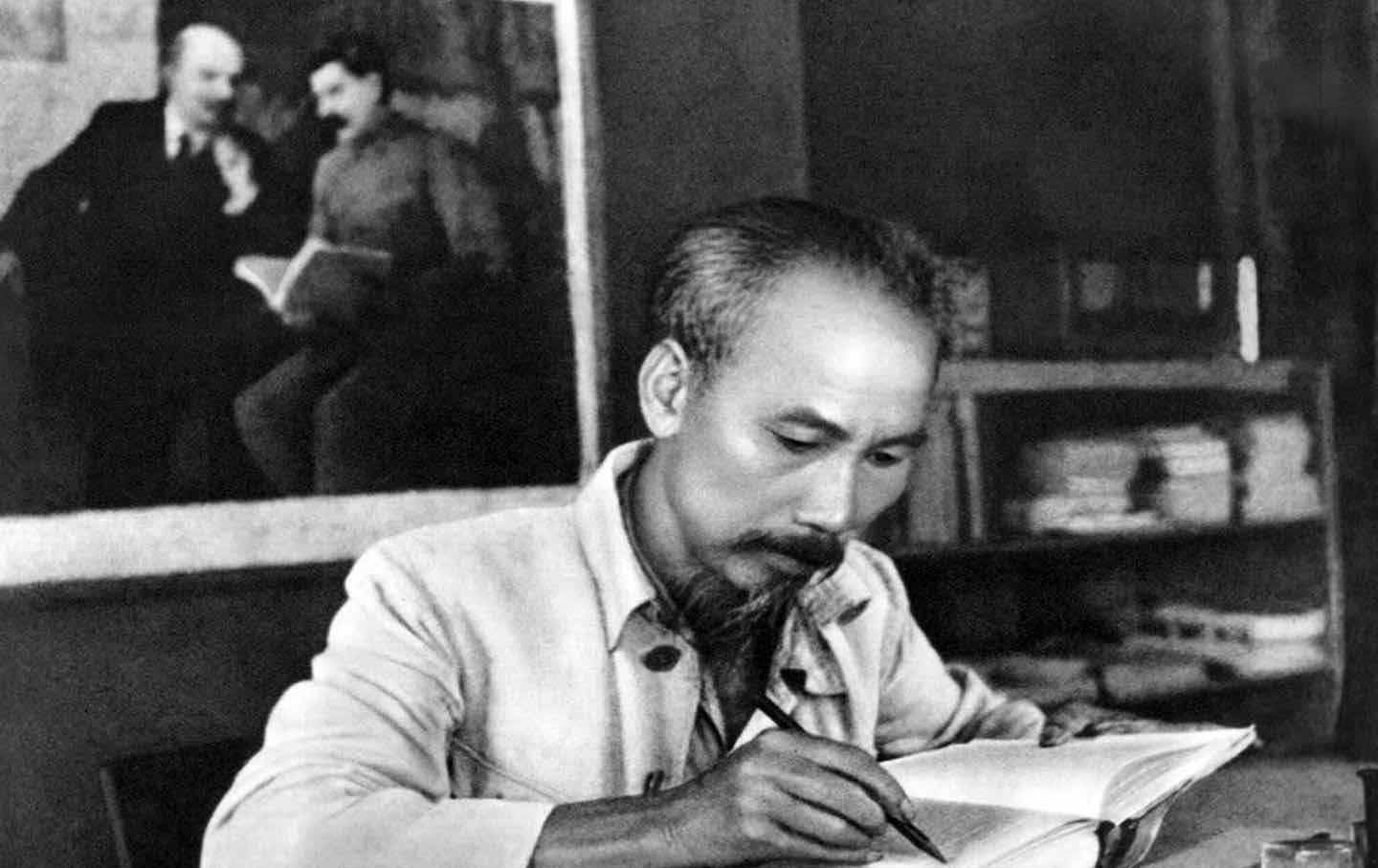

Hồ Chí Minh, 1950.

(Photo by Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In the summer of 1919, a Vietnamese radical landed on the radar of the French government. He was young, in his late 20s or early 30s, and had connections to the Vietnamese community of laborers, leftist intellectuals, and exiled activists in Paris. Officials couldn’t identify who the man was or where he came from, but because of his politics—he was an avowed critic of French colonialism and an advocate for Vietnamese independence—they deemed him a threat. The man regularly attended meetings held by the French Socialist Party (SFIO) and published frequent screeds in a French socialist newspaper, L’Humanité, condemning the state’s treatment of its colonial subjects. During the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, he penned a letter, alongside a group of fellow Vietnamese radicals, with demands to various world leaders on behalf of his countrymen. The demands consisted of judicial reform, the election of a permanent Vietnamese delegation to the French Parliament, and civil rights expansion in Vietnam, including freedom of speech and the press, association and assembly, and education. Titled “The Demands of the Vietnamese People,” it was signed “for the Group of Vietnamese Patriots, Nguyễn Ái Quốc.”

Books in review

Faraway the Southern Sky

Buy this book

Translated as Nguyễn “the Patriot who loves his country,” Ái Quốc was a clever, albeit obvious, alias to anyone fluent in Vietnamese. The pseudonym was employed by an underground group of Vietnamese socialists whom the future Hồ Chí Minh—the young radical in question—was affiliated with. The name offered the patriots some anonymity and protection from French intelligence, who struggled to pinpoint the figure behind the texts. It was also likely that different members were responsible for proposing ideas, translating, and disseminating the writings penned under the pseudonym.

These collective efforts, however, have become a footnote in the story of Vietnamese independence. History remembers Nguyễn Ái Quốc as Hồ Chí Minh, an attribution that neglects the crucial groundwork done by seasoned radicals like Phan Châu Trinh and Phan Văn Trường, who mentored and housed the young Hồ in Paris. Of course, Hồ became the most public-facing agent who laid claim to the alias. He met with French politicians and journalists and attended the Tours Congress, a 1920 French socialist conference, as Nguyễn Ái Quốc. At Tours, before an audience of over 300 attendees, he delivered an impassioned 12-minute speech urging the SFIO to support Indochina’s liberation. Curiously, the photo snapped of him there—a lean, boyish figure standing in a sea of seated, mustachioed Frenchmen—remains better known than the speech. Perhaps for good reason, as the picture gives a face to the name, a face that history can recognize, even though Hồ reportedly adopted from 50 to 200 aliases over his life.

“Hồ himself made a fetish of covering up his past,” writes historian Sophia Quinn-Judge in Hồ Chí Minh: The Missing Years, which focuses on Hồ’s political activities from 1919 to 1945—spanning his years as an underground (and later professional) revolutionary in France, Russia, and China before his return to Vietnam. “The biographical information he supplied over the years amounts to a variety of anecdotes and conflicting dates rather than a real record of his life.” As such, most biographical accounts vary in these minor inconsistencies, and the distinctions between known facts, researched conclusions, well-founded assumptions, and vague speculations regarding Hồ’s early life aren’t always so clear. By charting a chronological narrative of Hồ’s life, in the vein of a bildungsroman, biographers are at risk of blending party-approved hagiography with the limited historiography of his underground years.

For this very reason, the French writer Joseph Andras has little interest in Hồ “the icon, revered Supreme Leader…[with his] illustrious goatee enthroned in History somewhere between Lenin and Gandhi.” His fascination lies with Nguyễn Tất Thành, the Vietnamese radical who “changed names like he changed shirts” before he finally entered the historical record as Uncle Hồ. In Faraway the Southern Sky, his second novel translated to English, Andras embarks on a sprawling walking tour of contemporary Paris in search of this unknowable figure. He begins with a disclaimer that acknowledges the impossibility of such a task: “It’s this man, in exile, in the nooks of a capital just out of the war, that you go in search of, knowing you won’t find a thing.”

The resulting novel isn’t so much “a work of fiction based on facts,” to borrow a phrase from the Chilean novelist Benjamin Labatut, as Andras’s first novel, Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us (2016), was. A more accurate term may be “historical autofiction.” Andras grapples with his own sentimental and personal notions of Nguyễn, attempting to “assume the tension without seeking synthesis” between his rebel years and his presidency. Andras visits the various locales that Nguyễn reportedly lived and worked in like a detective-minded flâneur, pausing every now and then to take note of present-day Parisian life: the serrated blue rooftops of Gare Saint-Lazare station, the barricades raised along the Seine, the old graffiti, the police patrolling Place de Clichy, where a suspicious package had been left behind. There’s a cinematic quality to the ambling commentary. The speaker’s gaze glides over people, foliage, and storefronts alike. His descriptions are precise, almost Acmeist in its emphasis on brevity: “The sky is like a sea the wind forgot…. A mottled tent shields the body it shelters from the eyes of passersby.”

Current Issue

Andras employs the second person, a depersonalized “you,” shifting the speaker’s subjectivity away from himself and tying the authorial perspective to the reader. Via this confrontational mode of address, the reader is enmeshed with the “you” of the narrative, regardless of political persuasion or knowledge of Paris. This subjective subversion can be jarring initially, given how Andras is our primary eyewitness through Nguyễn’s labyrinthine past. Nevertheless, the narrative style is effective in imparting a distance between Andras and the reader, a reversal of that tired cliché “The personal is political.”

Andras addresses the personal with recalcitrance, and only in relation to the political. “To talk of the self while society only swears by it deserves at least a word of apology,” he admits; “when the singular rules, literature must head the opposition—in lowering heads that stick out.” A trip to Vietnam, likely as research for the book itself, is reduced to a single paragraph, a pile of almost-forgotten notes. Andras’s politics steer most of the novel’s present-day digressions, from pedestrian observations—passing by the Eiffel Tower, the speaker recalls a protest he participated in on a recent Saturday—to ideological ruminations on how history is manufactured and maintained. “This merits the term irony,” he notes: “liberal democracies ended up establishing what no totalitarian regime could have ever put in place: files, updated daily, on every citizen.” These wanderings are short-lived; the speaker’s detours are taut and restrained, like a dog kept on a tight leash, and he is seemingly led by instinct back to Nguyễn every time.

Faraway traces the year of Nguyễn’s arrival in Paris to 1918, a date, as the speaker admits, that remains contested by historians and biographers, give or take a year. “But maybe none of this is important,” he says. And later, “No one knows. Or we know very little.” These disclaimers are peppered throughout the text, examples of Andras contending with and counteracting history’s exacting preference for certitude. Even so, the novel’s bibliography cites seven biographies written in French or English for research, in addition to Hồ’s autobiographies and later writings on this period of his life. The most reliable details about Nguyễn’s Parisian activities and relationships are derived from the scrupulous accounts of French intelligence agents, who tightly monitored him at 6 Villa des Gobelins, when he was living with the Phans. Nguyễn unwittingly befriended two agents tasked with spying on him, Jean and Édouard, even as he worked to evade police observation. Still, when assessed with Nguyễn’s limited correspondence and published pseudonymous writings, these official documents amount to a rough sketch. We know Nguyễn worked as a photo retoucher in his day job and moonlighted as an activist until his sudden departure for Moscow in 1923. Here, rumor is distinguished from reality, though these tidbits of truth are cherry-picked from an array of witnesses and texts. Andras sought to selectively fill in these gaps, leaving the rest to his imagination.

He describes Nguyễn as a soft-spoken, albeit zealous newcomer, “knocking on the doors of [his] country’s greats during the day to plead for a cause all considered lost, and, come nightfall, warming his bed with a hot brick wrapped in old newspapers.” Nguyễn read Dickens, Tolstoy, and Romain Rollard and had few known lovers, though the documented names might have been a cover for counterintelligence. He is characterized as an affable radical, averse to debating the ins and outs of political theory, an everyman who used a copy of Capital as his pillow. The novel occasionally refers to him as “the Montmartre mute,” because he “stammered the moment he stepped forward in public” and repeatedly failed to take the floor at Socialist Party meetings. But Nguyễn’s political evolution burgeoned quickly, as did his self-assurance—developments which are narrated with rhapsodic zeal. The narrator is enamored by the image of Nguyễn as a bootstrapping rebel, penning manifestos in a language he had a loose grasp on, “alone in his room…[calling] out to an imaginary crowd that this is the path to liberation.”

Andras is aware of the lure of the “success story,” as he calls it, in misreading Nguyễn’s life in retrospect—accounting only for his victories and not his failures, particularly in containing the excesses of his homegrown movement. He admits to “[cutting] the man in half” to bypass Hồ’s failures as a leader. Still, the novel is not exempt from perpetuating the myth of Nguyễn’s revolutionary exceptionalism. Although Andras alludes to the opaque nature of Nguyễn’s identity (“the first person is plural”), the collective effort that molded him into Hồ Chí Minh, the new name he adopted in 1940, can get short shrift: An emphasis on the heroic rebel erases any notion of the plural in Nguyễn Ái Quốc’s political ascent.

Andras barely alludes to Nguyễn’s rebel roots in Indochina or his years abroad in London and the United States. His ties to the Phans, long-standing leaders of the anti-colonial cause in Paris, are similarly overlooked. Phan Văn Trường is acknowledged as a translator, someone who helped Nguyễn write the French text of the “Demands” during the Peace Conference and other works submitted to the French press, although the Phans likely had a larger role in the manifestos. In The Missing Years, Quinn-Judge agrees that “[Nguyễn] himself may well have been one of the moving forces behind the campaign for Vietnamese rights in Paris,” but his ascendance was no independent endeavor: “There is a case to be made that [Nguyễn] had already gained considerable political experience by 1919, that he had been consciously preparing himself during those years to play a role in liberating his nation from French rule.” He was about two decades younger than the Phans and well-positioned to be their successor.

However, events during the summer of 1921 introduced a minor rift to the collective: Nguyễn moved out of 6 Villa des Gobelins over a dispute with the other patriots, which Andras describes as “one hell of a row.” He implies that Nguyễn’s radical views were not shared by the group. Historians disagree over whether Nguyễn’s departure was occasioned by a significant falling-out or a minor disagreement. (Quinn-Judge notes that he still remained in touch with Phan Châu Trinh, and they attended SFIO meetings together.) However, Nguyễn was keen on establishing himself after the move, according to Andras. He started a new magazine, Le Paria, overseeing the editorial process and distribution to the colonies from his new residence. Le Paria occupied most of Nguyễn’s time during his final two years in Paris, a period that the novel skims over. The biographical conclusion feels rushed, much like Nguyễn’s abrupt departure for Moscow in 1923. Colleagues and friends thought he was simply taking a holiday. Because Faraway’s purview is geographically limited to Paris, the novel is lodged in a limbo in time. Indeed, every novel should strive to be a world unto itself, but the challenge with a project like Faraway is its synthesis: Can the ideas cohere beyond a mere collection of notes?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Andras denies the impulse to “psychologize history,” but by the end, I wished the novel had delved into the speaker’s affinity for Nguyễn, why he found his early life so moving, or how “the dead haunt the fabulist lives of the living.” The closest we get to such subjectivity is when Andras leaves behind the revolutionary past for the present, walking past protest barriers and armored vehicles to witness “a capital rising up.” These streetside observations are an essential window to Paris that opens up as the novel progresses. The narration is lush and lyrical, occasionally punctuated with a poem or a quote, but there remains a staunch refusal to dive into the muddied waters of one’s wandering psyche. This tension emerges from the speaker’s desire to recognize the collective politics of protest, which he tries to balance against his fascination with how a lowly rebel can be fashioned into a world-historical man. In order for a figure to undergo this transformation, Andras writes, “there must be a threshold to cross: a definitive border between two conditions, between those who die and those whom death doesn’t kill.” As a novelist, Andras understands that narrative can help bestow immortality upon individuals whose fates have been suppressed or simply forgotten. The novelist, like the biographer, is capable of rewriting and even reviving the dead, to allow us to understand them anew. If only Andras had taken more liberties, under fiction’s protective guise, to affirm his belief that beyond any single leader or man, “the masses are the makers of history.”

More from The Nation

A long awaited English translation of her shocking magnum opus, The Children of the Dead, asks its readers to look at the violent history buried just beneath their feet.

Books & the Arts

/

John Semley

A recent book argues that reordering the stages of work and life—including retirement—could eradicate conflicts between generations, while ignoring the real issues that divide us….

Books & the Arts

/

Julian Epp

The playwright’s remarkable debut film, Janet Planet, immerses the viewer in the sounds and sorrow of a middle-schooler’s endless summer.

Books & the Arts

/

Nora Caplan-Bricker

The Academy’s film museum, seeking to placate critics who decried its earlier omission of Jewish moguls, rushes to fix its clumsy handling of a sensitive subject.

Ben Schwartz

Peter S. Goodman’s recent book on the pandemic’s effect on global rhythms of supply and demand tries to answer why “the world ran out of everything.”

Books & the Arts

/

Brett Christophers