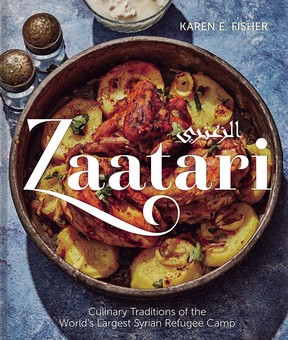

Newfoundlander Karen E. Fisher collaborated with more than 2,000 Syrians to create the Zaatari cookbook, filled with stories of art, culture and food

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

Article content

Our cookbook of the week is Zaatari by Karen E. Fisher, a professor at the Information School, University of Washington, and an embedded field researcher with UNHCR Jordan from St. John’s, Nfld.

Jump to the recipes: shish barak, meat-filled dumplings known as “old man’s ear” because of their shape; tesqieh, a delectable dish based on torn pieces of day-old bread; and qatayef, small pancakes filled with cinnamon-scented nuts and served with rose-infused cream.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Karen E. Fisher started writing a cookbook about the food culture of Zaatari, the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp, in 2016, a year after she arrived as an embedded field researcher with the UNHCR Jordan. “If Zaatari had a guest book, I’d peg as the only Newfoundlander.”

Originally from St. John’s, Fisher divides her time between Zaatari Camp on the Jordanian-Syrian border and Seattle, where she’s a professor at the Information School, University of Washington. The purpose of her first trip to Zaatari in January 2015 was to look at how young people in the camp use mobile phones and the internet. As a design ethnographer, she has a broad skill set, which she sums up as focusing on people, information and everyday life.

Home to more than 80,000 people displaced by the Syrian civil war, Zaatari is a closed refugee camp, meaning visitors require an invitation and security clearance. Fisher describes her role there as unique: she’s not on the UNHCR’s payroll and doesn’t wear a uniform. Unlike visitors, who have escorts accompanying them to approved places, she walks around Zaatari freely, meeting up with Syrians and visiting their homes. Many residents have mistaken her for a Syrian living in the camp, though “as soon as I say something (in Arabic), they know that I’m not,” she says, laughing.

Advertisement 3

Article content

More than 2,000 Syrians handwrote pages of what became Zaatari, the cookbook. The camp Facebook group served as Fisher’s fact checkers, and many residents helped with the final draft. Food photographers Alex Lau and Jason LeCras shot 80 per cent of the recipes in the camp’s caravans and souks with the help of youth from Lens on Life/Questscope, and residents took most of the photos of daily life. “It is truly a book of the community. And the royalties are returned to Zaatari Camp, which is a wonderful problem they’re going to have about how to spend the money,” says Fisher.

Food is the foundation of the book, interwoven with art, poetry and stories of all aspects of life in Zaatari Camp: a trip to the barbershop and beauty salon, wedding customs, how residents welcome newborns and celebrate Ramadan (expected to begin on March 10 and end on April 9 this year), the world’s first refugee-run library system, Zaatari Camp Libraries, and TIGER (These Inspiring Girls Enjoy Reading).

“You wouldn’t be able to understand the food of Zaatari without understanding the culture,” says Fisher. “It’s the history, it’s language, it’s music and definitely Islam.”

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

When developing the recipes for the book, Fisher first searched for mentions of the ingredients in the Qur’an. She would then look at ancient cookbooks, the oldest of which is from Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). “It was just fascinating to find out how these recipes have morphed. All of that is related to what we call Arab medicine, Arab healing, which is why I also have a small section of the book called ‘Arab Medicine with the Elders’ — because it’s so different. They don’t have pharmacies like we see in the West. You go into the spice shop, and almost everything you need to be healthy is there.” Advice for treating a headache includes drinking water with rosewater or peppermint chai; for insomnia, sipping chai with anise or shaneena (yogurt drink).

Zaatari Camp opened in 2012 to house people fleeing from Syria. As Dominik Bartsch, UNHCR representative to Jordan, highlights in the book’s foreword, a new generation of children born in the camp have never been there. Carrying on culinary traditions connects them to their homeland.

For the past 10 years, Fisher has focused on domicide: “What happens when people’s homes and communities are destroyed? How do we preserve Indigenous knowledge? How do we keep the culture going? And so much happens with war. Entire social structures get destroyed. It’s just really, really horrific.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

One of the reasons Fisher wanted to write the book was to document culinary traditions from southern Syria. Most Zaatari residents are from Daraa, a region in the south known as the “cradle of the revolution.” She highlights significant regional differences between the food in Aleppo and Damascus, for example, and Daraa. “And these are the recipes that the world did not have. These techniques for cooking from the south.”

Fisher learned about the food traditions of Zaatari by being there “with her sleeves rolled up.” Whether cooking with women in their homes or visiting souk stands and restaurants along the Shams Élysées (Zaatari’s market street), wherever there was food, she was taking it all in.

Before getting a PhD in library and information science at Western University, Fisher contemplated attending chef’s school. She grew up learning how to bake bread and raisin buns from her grandmothers in Newfoundland, which has its own unique food culture. As she spent more time in Zaatari, she began to see similarities in unlikely places.

“How all of this happens down in Newfoundland, we always have what we call the kitchen parties. Everything happens in the kitchen. And it’s very much the same in Zaatari.” One difference, though, is the scale. “When Zaatari cooks, they cook for large numbers of people. When they say ‘tray,’ they’re talking about a big, giant tray of something.”

Advertisement 6

Article content

One of Fisher’s favourite memories of food in Zaatari is from the end of Ramadan, as the camp prepared for the feast of Eid al-Fitr. The women gathered with their wooden moulds to make maamoul sameed (filled butter cookies made with semolina). One brought nuts, another dates and another semolina. Throughout the night, she heard the tap-tap-tapping of the moulds striking hard surfaces to release the shaped dough before baking.

As in Newfoundland, Zaatari food is social in the way it’s enjoyed and prepared — but also in how cooks share it with the community and those who are less fortunate.

This practice plays out at the feast welcoming newborns (aqeeqah). Fisher explains that twenty per cent of Zaatari Camp’s population is under four, and roughly 80 babies are born each week. A sheep is sacrificed (two for a boy, one for a girl) to celebrate the birth, and the barbecued meat is shared with the community.

“The older men in the family and other neighbourhood men will come, and they sit around and thread skewers. And that reminds me so much of being in Newfoundland, where my father and his friends would come in from their boat shooting turrs, these little black-winged birds, out on the ocean. Then the grandfathers would come out, and they all sat around for hours and hours cleaning the animals and preparing the food. It brought me home in a lot of ways.”

Advertisement 7

Article content

Author and photographer Marsha Tulk called this practice “Newfoundland food distribution” in a 2021 interview with the National Post. Fisher saw a parallel in Zaatari. “When you have something good, first you give thanks to God and share with your neighbours. You share with everybody. In Arabic, in Islam, they’ve called it ummah, the large community.”

Infusing the book with all aspects of life in Zaatari allowed Fisher to dig deep — to illustrate what drives the culture and explain what makes their food so delicious. “I’m sure I’ll never have this privilege in life again, to be able to work with a community this way and be considered part of that community.”

Recommended from Editorial

-

Cook This: Three recipes from Tiffy Cooks, including brown sugar milk tea with homemade boba pearls

-

Cook This: Three Caribbean recipes from East Winds, including a favourite Trini breakfast

SHISH BARAK

UMM YOUSEF, al-Musayfira

Filling:

3 tbsp (45 mL) oil or saman

1 cup (250 mL) fried pine nuts

1 onion, minced

1/2 lb (225 g) ground meat (see note)

1/4 tsp Aleppo pepper

1/2 tsp salt

1 tsp cinnamon

Dough:

8 cups (1 kg) flour

1/2 cup (125 mL) olive oil

1/4 tsp salt

2 cups (250 mL) water

Advertisement 8

Article content

Sauce:

4 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 cup (12.5 g) chopped coriander

6 cups (1.5 L) laban or full-fat yogurt

1 egg

2 tsp dried mint

3 tbsp tomato sauce

Step 1

For the filling, brown the pine nuts in oil and remove to small bowl. Add onion to oil and sauté until softened and add the meat, breaking it into pieces. As the meat browns, add the seasonings. Stir in fried pine nuts. Remove from heat and cover.

Step 2

For the dough, add the oil and salt to the flour and rub well. Add 1 1/2 cups (375 mL) water, and mix well. Add more water as needed to make a soft dough. Let the dough rest for 10 minutes, then shape into 4 balls. On a floured board, roll each ball to a thickness of 1/8 inch (0.3 cm). Cut the dough into circles. Fill each circle with a generous spoonful of the meat mixture, fold, pinch the edges to seal, and bring the tips together, creating a crescent shape. Dust the dumplings with flour to prevent sticking.

Step 3

For the sauce, sauté the garlic and coriander and set aside. Over medium heat, bring the laban with the egg and 1/2 cup (125 mL) of water to a boil, shaking constantly to prevent scorching. Add the garlic, coriander, mint, tomato sauce, and dumplings. Reduce the heat and simmer until the dumplings float to the surface.

Advertisement 9

Article content

Step 4

Ladle into bowls and enjoy.

Note: In Zaatari Camp, cooks use lamb, “but beef is also delicious,” says Fisher.

TESQIEH

UMM FAISAL, Elmah

3 rounds Khubz (or pita bread)

1/4 cup (60 mL) olive oil or saman

1 can (400 g/14 oz) chickpeas, drained and rinsed

2 cups (500 mL) full-fat yogurt

1/4 cup (60 mL) tahini

2 tsp minced garlic

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp chili powder

2 tbsp fresh lemon juice

1 tsp salt

1/2 tsp white or Aleppo pepper

Olive oil for drizzling

Garnishes: 1 cup (250 mL) chopped parsley, lemon wedges, 1 cup (250 mL) nuts (pine nuts, cashews, slivered almonds) fried in olive oil until golden, chopped tomatoes, pomegranate seeds

Step 1

Tear the bread into 1-inch (2.5 cm) pieces. In a large frying pan, heat the oil over medium heat and fry the bread until golden on both sides. Reserve 1 cup (140 g) and spread the remainder over a large serving dish.

Step 2

In a medium pot, add the chickpeas to 1 cup (250 mL) of water and simmer for 20 minutes. Drain, reserving half of the broth and 3 tbsp (30 g) of the chickpeas for garnish.

Step 3

In a medium bowl, combine the yogurt, tahini, garlic, and seasonings; taste and adjust.

Advertisement 10

Article content

Step 4

Pour the chickpea broth over the bread, add the chickpeas, and stir to combine. Top with the yogurt mixture. Garnish quickly with the reserved fried bread and chickpeas and the other garnishes. Drizzle with oil. Serve hot.

QATAYEF

UMM ABDALLAH and UMM FIRAS, Damascus, al-Hara

Syrup:

2 1/2 cups (500 g) sugar

1 cup (250 mL) water

1 tsp fresh lemon juice

2 tsp rosewater, or 1/2 tsp orange blossom water

Pancakes:

1 1/2 cups (187 g) flour

1/2 cup (100 g) coarse semolina

2 tbsp sugar

2 tbsp powdered milk

1 tsp baking powder

1/2 tsp salt

1 tsp instant yeast

2 cups (500 mL) warm water

1 tsp vanilla extract

Saman or vegetable oil for frying

Joz filling:

1 cup (140 g) fried nuts (pine nuts, walnuts, hazelnuts)

1 tsp ground cinnamon

2 tbsp sugar

1 tbsp saman

Qishta:

1 cup (250 mL) heavy (whipping) cream

1/2 cup (125 mL) full-fat (whole) milk

2 tbsp cornstarch

1 tbsp sugar

1/2 tsp either rosewater, orange blossom water, vanilla, or ground mastic

Garnish: coconut (sweetened or unsweetened), finely chopped nuts, dried rose petals

Step 1

First, prepare the syrup. In a saucepan, combine the sugar and water. Bring to a boil and add the lemon juice, then lower the heat and simmer for 8-10 minutes. Remove from heat and stir in the rosewater. Pour into a deep bowl and cool to room temperature.

Advertisement 11

Article content

Step 2

For the pancakes, in a large bowl mix the dry ingredients. Add half the water and the vanilla. Stir well and gradually add the remainder of the water. The batter should be velvety smooth and liquid; if it is thick, add more water, tablespoon by tablespoon. Cover and set aside for 1 hour or until bubbly and slightly risen — this helps tenderize the semolina.

Step 3

Heat a large frying pan over medium heat and add saman or vegetable oil. Stir the batter well. Pour 2 tbsp into the pan, using a spoon to make small circles 3 inches (8 cm) apart. Cook for 1-2 minutes or until bubbles form on top and the pancakes are brown underneath. Place in a single layer on a linen tea towel and cover with another to keep the qatayef from drying out.

Step 4

For the filling, in a small bowl, combine the nuts, cinnamon, and sugar with a fork. Add enough saman so that the mixture is crumbly and glistens.

Step 5

For the qishta, in a medium saucepan, whisk together the cream, milk, cornstarch, and sugar until smooth. Over medium-low heat, whisk constantly until it boils and thickens. Stir in the rosewater. Pour into a bowl and cover with plastic wrap with the plastic touching the cream to prevent a skin from forming. Refrigerate for at least 2 hours. Stir before using.

Advertisement 12

Article content

Step 6

Place 1 1/2 tsp (7.5 mL) of the filling in each qatayef, bubbly side up and brown side down, fold in half, pinch the sides to seal, and set aside.

Step 7

In a large pot, heat 3 inches (8 cm) of oil over high heat. Fry the qatayef in batches, 2-3 minutes on each side until browned. Drain on a paper towel and dip the hot qatayef in the cold syrup.

Step 8

Place on a platter and dust with powdered sugar. Garnish and serve with the qishta.

Recipes and images excerpted from Zaatari by Karen E. Fisher. Copyright ©2024 Karen E. Fisher. Food photography by Alex Lau with Jason LeCras. Published by Goose Lane Editions. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our cookbook and recipe newsletter, Cook This, here.

Article content