The third repatriation flight of Brazilians from Lebanon arrived in Sao Paulo on Thursday (10/10) with 218 passengers on board a Brazilian Air Force (FAB) flight. The first three repatriation flights from Lebanon have already brought 674 people and 11 pets to Brazil.

Lebanon is the country with the largest number of Brazilians in the Middle East, estimated at 21 thousand people.

Efforts to rescue some of these citizens, who sought repatriation amid the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, have drawn attention to the deep ties between Brazil and Lebanon.

In addition to Brazilians living in the country, the relationship is strengthened by the large community of Lebanese and Lebanese descendants who immigrated to our country since the end of the 19th century.

According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 12,336 Lebanese lived in Brazil in 2010, the date of the last census with published results. This figure was 2.9% of the total number of foreigners in the country at that time.

But when talking about the Lebanese community in Brazil, the estimated numbers are much higher. Between citizens and descendants, the Brazil-Lebanon Cultural Association speaks of about 8 million people.

This makes Brazil the largest country of Lebanese and descendants in the world, surpassing Lebanon's current population of 5.5 million.

But how did the two countries, despite their distance and cultural differences, develop strong ties?

For the Lebanese diaspora

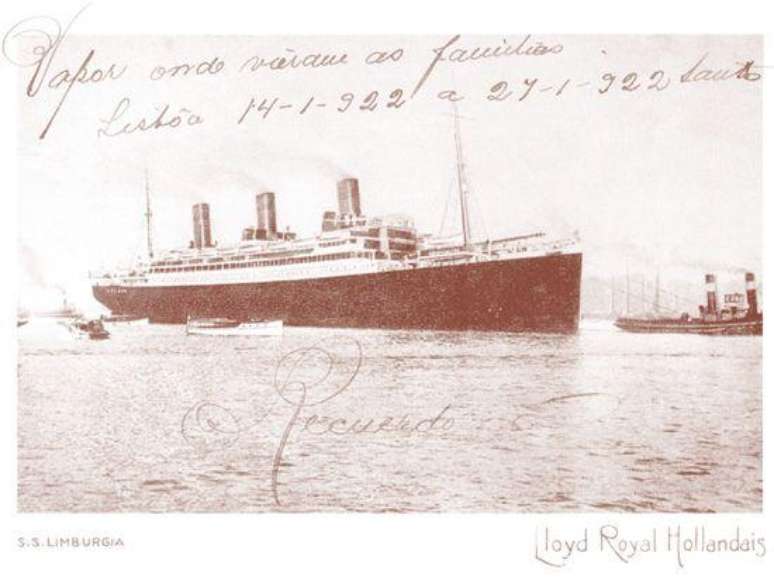

The great flow of Lebanese immigration to Brazil began at the end of the 19th century from Beirut to the port of Santos.

At the time, what is now Lebanon was under the rule of the Turkish-Ottoman Empire and dissatisfaction with the political, economic and religious situation prompted an emigration.

“Many Christians suffered religious persecution, while work and land became increasingly scarce,” said Nouha B., cultural director of the Brazil-Lebanon Cultural Association. Nader says.

Osvaldo Truzzi, professor at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and expert in the sociology of migration, explains that the influx of cheap industrialized goods from England and France at the same time raised the tide of migration.

“A vast amount of manufactured goods began to flood local markets, undermining home and small-scale production by many families in the interior of the country,” he says. “This has led many families to send some members abroad to help them make ends meet.”

Druzi also says that a military coup in the Ottoman Empire in 1909, before the outbreak of World War I, prompted many young people to flee the country.

Finally, part of the responsibility is attributed to Emperor Dom Pedro II. The last king of the Brazilian Empire, when he visited Lebanon in 1876, promoted the country to the local population.

“He told the locals that Brazil was a land of wealth and prosperity, with good job opportunities,” says Nader.

According to the director of the Brazil-Lebanon Cultural Association, newspapers at the time reported the information widely, which helped create a positive image of the country among the public.

Destination: USA

Most Lebanese who left their homeland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries headed for the United States.

This group is mainly made up of Christians, who were attracted to the area due to religious affinity.

Between 1870 and 1930, there are records of about 330,000 emigrants from what became known as Bilad al-Sham or “Greater Syria” (the territories that today include Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, and Israel). in Immigrant Studies from North Carolina State University.

About 120,000 of these migrants went to the United States and another 210,000 to South America, mainly Argentina and Brazil.

At the time, documents did not distinguish the exact origins of immigrants, which made it difficult to accurately count Lebanese immigrants.

But according to Osvaldo Truzzi, initially the largest group went to America, where they believed there were better economic opportunities.

However, little by little, the success of the families who chose Brazil as their new home began to attract more and more interested parties, leading the community to grow.

Between 1884 and 1933, 130,000 Syrians and Lebanese entered Brazil through the port of Santos, according to researcher Jeffrey Lesser, professor of history at Emory University and director of the Latin American and Caribbean Studies Program.

Around this time, the first Brazilian embassy was opened in Beirut in 1911.

“Brazil did not have a developed middle class then. We had landowners and poor people, descendants of former slaves”, says sociologist Osvaldo Truzzi. “It gave the Lebanese a place to integrate themselves into the business sector and enjoy economic boom and social mobility.”

The community settled mainly in the state of São Paulo, where a commercial center had already begun to develop around the coffee economy. But some Lebanese migrated during the rubber boom to other states such as Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and, to a lesser extent, the Amazonas.

After the first wave of immigration, Brazil received at least two major Lebanese waves: one between 1921 and 1940, with a Christian majority, and a second between 1941 and 1970, with predominantly Muslim immigrants leaving their country due to sectarian conflicts. Christmas.

The flow has slowed since then, but Brazil is receiving Lebanese, especially from the south of the country.

Return to Lebanon

At the same time, some Lebanese with families in Lebanon and their descendants returned, forming a Brazilian community in the Middle Eastern country.

“Some are permanently relocated, others come and go as opportunities arise,” Trusey explains. The researcher also says that many of these Brazilian immigrants develop ties between Brazil and Lebanon by working in the export and import sector between the two countries.

Between January and September 2024, Brazil exported the equivalent of US$345.9 million to Lebanon and imported US$1.4 million.

Nouha Nader of the Brazil-Lebanon Cultural Association said that many people of Lebanese descent left the country and returned to Lebanon in the 1980s and 1990s, when Brazil entered an economic crisis that could only be dispelled by the consolidation of a real project.

“The Lebanese and their descendants who lived here, were very dependent on trade, and then decided to carry their Brazilian roots with them to Lebanon”, he says. “The majority are in the Beca Valley, where they speak Portuguese and eat the food here.”

Nader also cites Avenida República do Libano in São Paulo and Rua Brasil near the port of Beirut, and many cultural and artistic exchanges as part of the strong ties between the two countries.