Lawyers for a Black defendant challenging his 2009 death sentence argued Wednesday that North Carolina’s documented history of racial discrimination and perceived implicit bias in jury selection supports his claim that he should be resentenced to life in prison.

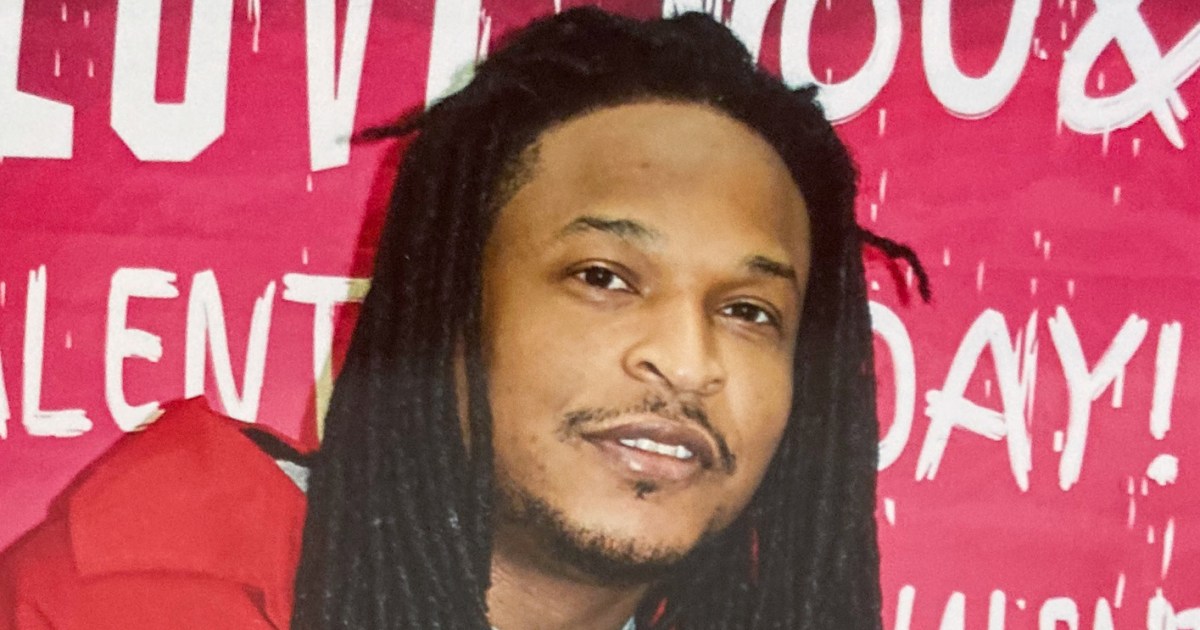

If that were to happen in the case of Hasson Bacote, who was sentenced to death by 10 white and two Black jurors for his role in a felony murder in Johnston County, more than 100 others on the state’s death row could see their sentences similarly commuted.

White jurors “get shown the box. Black jurors with the same background get shown the door,” Henderson Hill, senior counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union, said during closing arguments in Bacote’s trial court hearing.

His is the lead case testing the scope of North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act of 2009, which allowed death row inmates to seek resentences if they could show racial bias was a factor in their cases.

The landmark law was repealed in 2013 by then-Gov. Pat McCrory, who believed it created a “loophole to avoid the death penalty,” but the state Supreme Court in 2020 ruled in favor of many of the inmates, allowing those who had already filed challenges in their cases, like Bacote, to move ahead.

Lawyers from the North Carolina attorney general’s office in their closing argument disputed Bacote’s legal team’s analysis and the historical context as irrelevant.

If the test under the Racial Justice Act is “whether racism has existed in our state, then there is no need for a hearing in this case or any other case. But that’s not the question before this court,” state Department of Justice Attorney Jonathan Babb said. “Rather the question is whether this death sentence in this case was solely obtained on the basis of race. The defendant has not shown that his sentence was solely obtained on the basis of race.”

Now, Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons Jr. must weigh whether Bacote’s request for resentencing is warranted; legal experts have said doing so would set a precedent for the other death row inmates seeking relief. Sermons said he will issue a ruling, but gave no deadline.

When the Racial Justice Act first became law, nearly every person on death row, including both Black and white prisoners, filed for reviews, according to The Associated Press. There are currently 136 inmates on North Carolina’s death row, of which 75 are Black, 51 are white and the remaining 10 are another race, according to the state Department of Adult Correction.

North Carolina has not executed anyone since 2006, in part due to legal disputes and difficulties obtaining lethal injection drugs.

The state isn’t the only one where allegations of biased jury selection has led to a review of death penalty cases. In California, the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office began re-examining cases this year following evidence of prosecutors unfairly excluding Black and Jewish jurors from a 1995 trial.

During two weeks of testimony earlier this year in Bacote’s hearing, his lawyers called several historians, social scientists, statisticians and others to establish a history and pattern of discrimination used in jury selection, both in Bacote’s trial and others in Johnston County, a majority-white suburban county of Raleigh that once prominently displayed Ku Klux Klan billboards during the Jim Crow era. The state had also provided 680,000 pages of discovery, including its notes on jury selection in 176 capital cases between 1985 and 2011.

Ashley Burrell, senior counsel at the Legal Defense Fund, which is also representing Bacote, explained during closing arguments how the statistics bear out racial disparities in death penalty cases. In Johnston County, Burrell said that of the 17 capital cases reviewed, all six Black defendants were sentenced to death, while of the remaining 11 cases featuring white defendants, more than half of those individuals were spared death sentences.

Burrell said the various stats weren’t the only evidence produced, but also explained how Black men at trials have historically been referred to in derogatory and racialized ways to “evoke dangerousness.” In Bacote’s case, she said, a prosecutor during closing arguments at his capital trial referred to him as a “thug, cold-hearted and without remorse.”

Such language “taps into this false narrative of the super predator myth,” Burrell said.

Bacote’s lawyers also said that local prosecutors at the time of Bacote’ trial were nearly two times more likely to exclude people of color from jury service than to exclude whites, and in Bacote’s case, prosecutors chose to strike prospective Black jurors from the jury pool at more than three times the rate of prospective white jurors.

State prosecutors, however, questioned the stats used by Bacote’s legal team and how some of their experts could not testify specifically to his case.

North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein had sought to delay Bacote’s hearing, arguing in a court filing that the claims made by Bacote’s lawyers were based, in part, on a Michigan State University study that the North Carolina Supreme Court had already found last year to be “unreliable and fatally flawed.”

While the state attorney general’s office said in its court filing that racial bias in jury selection is “abhorrent,” according to NBC affiliate WRAL in Raleigh, the office added that a “claim of racial discrimination cannot be presumed based on the mere assertion of a defendant; it must be proved.”

Stein is the Democratic nominee in North Carolina’s gubernatorial race. His office declined to comment because the litigation is ongoing.

In light of the Racial Justice Act being repealed, term-limited Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, has faced calls from anti-death penalty advocates to commute the sentences of the remaining death row inmates before he leaves office.

Stein has expressed support for the death penalty while ensuring capital cases are free from racial discrimination. His Republican opponent, Mark Robinson, said in a public safety plan he unveiled Wednesday that he would “reinstate the death penalty for those that kill police and corrections officers.”

“I hope that somebody in the governor’s office has been watching this case and I’m hoping the governor has been paying attention to this evidence,” said Cassandra Stubbs, the director of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project.

Bacote, 38, remains held on a first-degree murder conviction in a Raleigh prison. He was charged along with two others in the 2007 fatal shooting of Anthony Surles, 18, during a home robbery attempt when Bacote was 20. The other two defendants in the case were convicted on lesser charges and later released from prison.