The outcome is a win for abortion rights, but the court left open the possibility of future challenges to the FDA’s regulation of mifepristone.

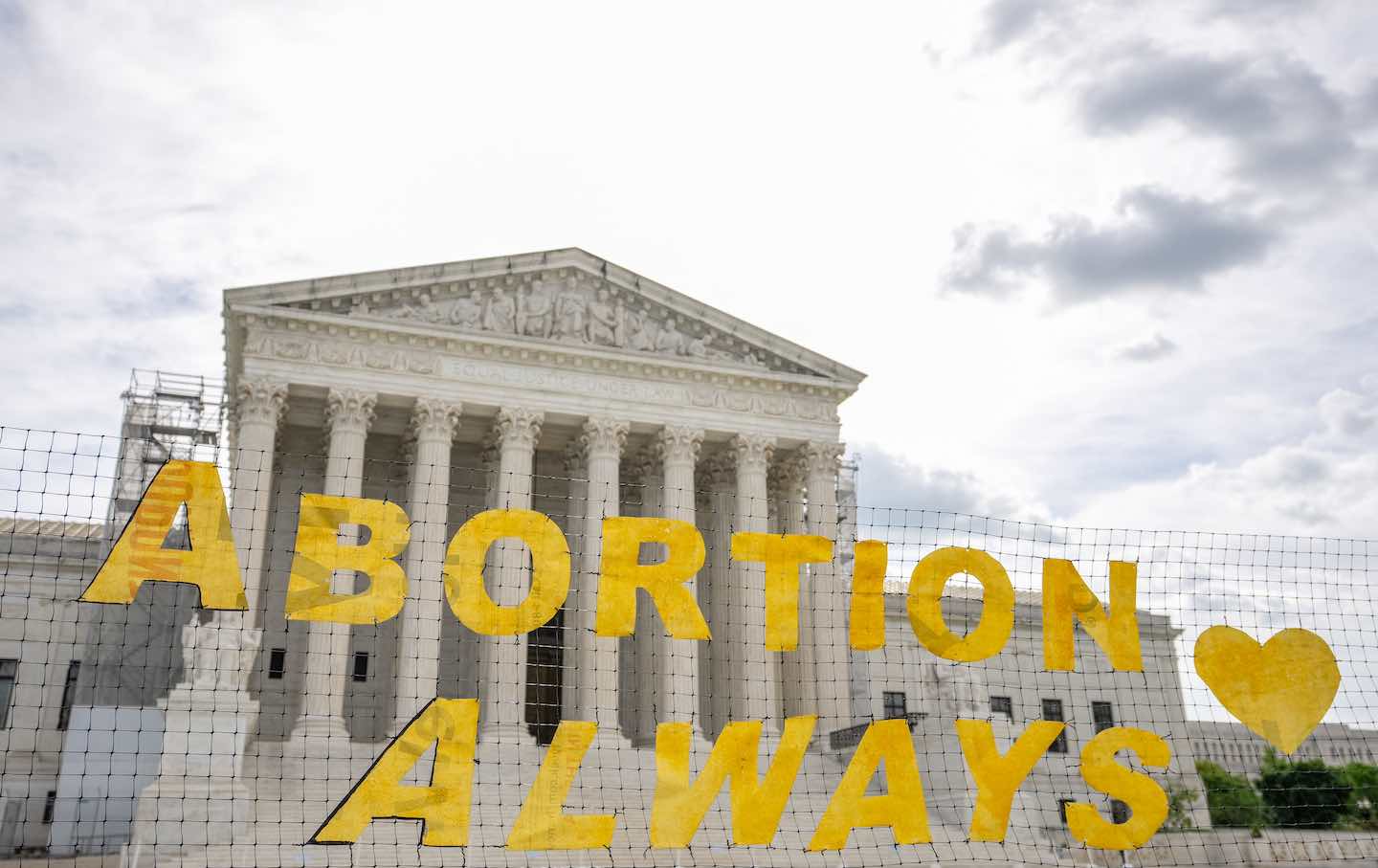

Abortion rights supporters display a sign that reads “Abortion Always” outside the Supreme Court Building on April 24, 2024.

(Photo by Andrew Harnik / Getty Images)

When the US Supreme Court held Thursday that the plaintiffs in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA do not have standing to bring a challenge to the FDA’s regulation of mifepristone, despite their “sincere, legal, moral, ideological, and policy objections to elective abortion,” the justices stopped short of asserting that it is the FDA that has the authority to regulate drugs in the United States. Instead, the court left open the possibility of future challenges to the FDA’s regulation of the abortion pill when Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who wrote the opinion in the unanimous decision, noted that, while these plaintiffs lacked standing, “it is not clear that no one else would have standing to challenge the FDA’s relaxed regulation of mifepristone.”

This ambiguity is very important. Since the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision overturning the national right to abortion, pregnant patients have faced organ failure, near-death experiences, and lengthy wait times and out-of-state travel to access abortion care. Medication abortion, which accounts for more than half of all abortions in the country, has become central to the fight for access to the full range of reproductive health services, including abortion.

From its onset, this case was about which branch of government should regulate medication abortions—the FDA or the Supreme Court.

The answer isn’t straightforward: While the FDA is the correct body to regulate drugs, the hard truth is that, as reproductive rights activists have argued, both the federal agency and the Supreme Court have been entangled in political battles around mifepristone—the first of two pills in the medication abortion regimen—and both institutions are guilty of validating the idea forwarded by anti-abortion advocates that mifepristone is not safe.

Mifepristone was in use in France before its approval by the FDA. Peer-reviewed data showed that the drug was safe and effective. When the FDA approved the drug in 2000, the agency placed the drug under a strict regulatory protocol, over the objections of health advocates. In doing so, the FDA validated an anti-abortion talking point that there was something potentially harmful about mifepristone. In reality, the drug was safe and would eventually be considered safer than penicillin and Viagra.

Reproductive rights activists and public health experts, with safety data on their side, pushed for greater availability of the drug, and in 2016, the FDA finally began to loosen regulations to allow mifepristone to be used further into pregnancy and at a lower dose. In 2021, with the pandemic in full swing, and when getting to a physician’s office was often impossible and risked exposure to Covid-19, the agency dropped the in-person requirement. People could finally end their own pregnancies without first traveling to a clinic for the medication.

Current Issue

Today, mifepristone has been used legally in the United States for nearly 24 years. Adverse consequences are rare—only 0.3 percent faced serious medical complications.

The physicians in AHM v. FDA, challenging the 2000 approval of the medication, as well as the 2016 and 2021 modifications to the FDA protocol for its distribution, asserted that they have been forced to treat the adverse outcomes of medication abortion against their own beliefs. Despite questions about the legitimacy of their claims, the group claimed victory in 2023 when the conservative Fifth Circuit put the older protocol back into place, undoing progress made in 2016 and 2021.

Disturbingly, the Fifth Circuit ruling relied on studies and “experts” who claimed that mifepristone was unsafe. The studies were retracted by the journals that published them as biased and methodologically unsound. As a way to ensure integrity and transparency in scientific and medical publishing, authors typically disclose affiliations that might produce conflicts of interest. Many of the authors of the retracted journal articles are affiliated with anti-abortion groups but did not disclose this fact, which suggests an attempt to hide political affiliations. Further, independent analysis of the data revealed statistical flaws resulting in misleading interpretations of the data.

Why would the court even rely on these studies? The historically conservative appellate court needed to substantiate the claim that the hypothetical scenarios proposed by the physicians in which medication abortion goes wrong and forces them to treat patients in emergency rooms violate their own values. Claiming that mifepristone is unsafe helps justify the anti-abortion physician’s questionable legal standing by making it seem that the hypothetical situations they pose—where mifepristone use goes wrong—is possible. It also generates a specter of uncertainty about the FDA’s ability to even judge the safety record of the drug. Making explicit the need to question the FDA’s authority, Justice Ho, concurring in part and dissenting in part, spoke to the FDA ’s experts as “human beings just like the rest of us,” who “make mistakes.”

While the plaintiffs did not succeed in convincing the Supreme Court that they have legal standing, the case helped continue to sow doubts about the FDA’s ability to effectively regulate drugs. This claim lands in fertile ground: Since the pandemic began in 2020, the agency has become the focus of a series of political attacks on vaccinations and the agency’s ability to track adverse events. Today, the confusion created after anti-vaxxers sowed doubt in the FDA and its regulatory authority aligns nicely with a long-standing conservative project to dismantle the administrative state. For the Supreme Court itself, it provides opportunity to lean into falsehoods which would be in line with the courts’ habitual practice of relying on or manufacturing factual claims about abortion to suggest that abortion is unsafe.

The Supreme Court should have made clear that the regulation of drugs ought to be left to the FDA both given the agency’s expertise and the FDA’s mandate and authority to regulate drugs. But it didn’t. So even though the court on Thursday deferred to the FDA in its ruling, abortion rights activists will have to remain vigilant as anti-abortion advocates fight to exploit every opportunity to undermine the safety profile of mifepristone, from attempting to publish in peer-reviewed journals or using the FDA’s own public participation mechanisms to challenge reproductive rights.

Mifepristone is a very safe medication. Reproductive rights advocates must continue to call out attempts to undermine this fact, wherever and whenever it surfaces.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply-reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish everyday at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation