The housing crisis is the logical outcome of real estate speculation and expanding unemployment—not an inevitable fact of life.

Decades of liberal advocacy preaching “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” have led us directly to City of Grants Pass v. Johnson. The case, for which the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in April, will determine whether the law, in its majestic equality, deems it “cruel and unusual” to penalize anyone for sleeping on public property. Concern with ameliorating people’s suffering is understandable. But the liberal position on homelessness has encouraged ceding important ground in favor of securing palliative interventions that will be palatable to governing elites. As a price of gaining support for helping homeless people as individuals, this compromise accepts homelessness as a fact of life, or an ecological condition, to which individuals can succumb.

The demand for public housing for people in need has given way to a conversation about individual trauma and therapeutic intervention. The center of gravity of the debate about homelessness has been reduced to just-so stories about why individuals, or supposed categories of individuals, are homeless. (Turns out that many/most/all of them really don’t want to live indoors! Who’d have known?) Therefore, we’re told, providing housing isn’t really the answer to homelessness.

In typical liberal-speak, “the homeless” are rendered the equivalent of an ethnic interest group, which sharpens attention to what kinds of services—other than housing, of course—their “community” needs. What results are absurdities: neologisms that supposedly remove the stigma supposedly attached to the word “homeless” while leaving the roots of the problem intact.

Though homelessness is experienced by individuals, it originates in the publicly supported political economy of privately appropriated real estate development and speculation, on the one hand, which push housing costs up, and the expansion of low-wage employment and underemployment, on the other. After decades of debates and policies that sidestep those realities, most people are unable to perceive the connection between homelessness, labor, and real estate markets, even as they experience the pressure of escalating housing costs in their own lives. Elites and their academic guide dogs insist that the roots of homelessness are behavioral rather than connected to market forces, and even liberal local governing regimes claim that intervention in housing markets is unthinkable. The general population does not understand the growth of homelessness as the logical outcome of prevailing market processes, seeing it only as a problem to be managed.

The bipartisan sanctification of property rights at the expense of social needs means that people who are less housing-insecure “naturally” experience the homeless population’s increasing visibility along a strictly limited continuum, ranging from inconvenience and aesthetic displeasure, to violations of the presumed (homeowner’s) right to insulate oneself from exposure to interlopers, to a threat to safety. In this moment of generally increasing insecurity and what Stephen Jay Gould called the “destruction of social generosity,” the conditions are ripe for those “for their own good” initiatives that remove the blighted, and blighting, population to somewhere out of sight. We all know how that can play out.

Homelessness has intensified steadily all over the country, and because the most obvious corrective responses are off-limits ideologically, officials respond mainly with bromides and measures that punish people who embody the problem. Restrictions on feeding homeless people, or “food sharing,” have been around since well before Covid but have risen in public awareness more recently as homelessness has become more visible. Last July, three New Orleans city councilmembers—all Black, but does that really mean anything?—floated a copycat version of Houston’s odious don’t-feed-the-homeless ordinance. The council tabled it after considerable public criticism. Eugene Green, one of the sponsors of the ordinance, in a nonresponse to critics (including myself) on the Nextdoor platform, referred, oh so carefully and respectfully, to “those who are unhoused,” while defending the clearly punitive proposal as being intended to address a public health concern.

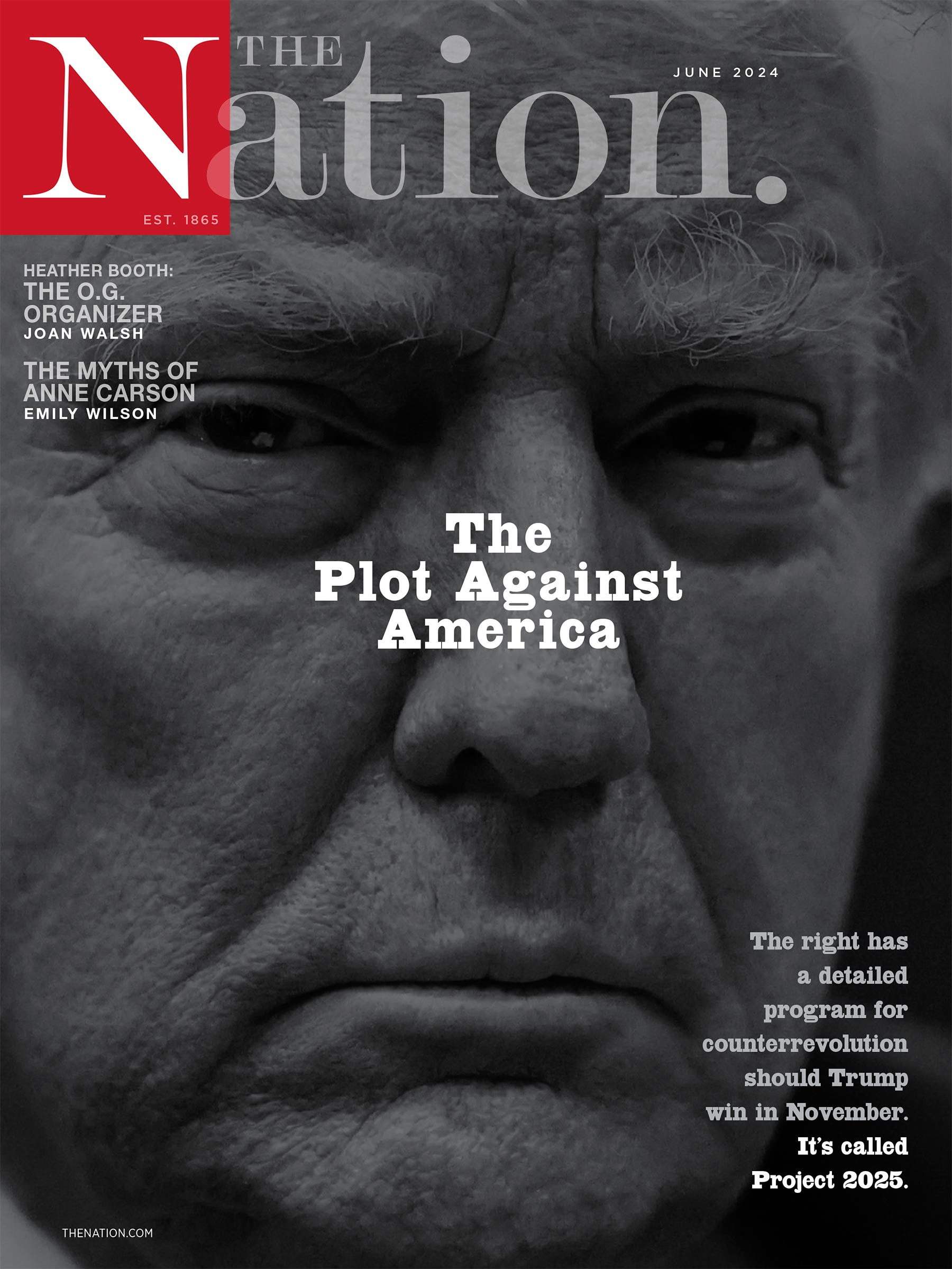

Current Issue

Similarly punitive, racializing interventions have been couched in a language of concern about public health ever since the field’s Victorian origins, including eugenicists’ racial hygiene campaigns and the Nazis’ original euthanasia program. Suppressing people “for their own good,” moreover, is a trope as old as the ruling-class need to manage hegemony—just think of John C. Calhoun’s felicitous discovery that slavery was a “positive good” for all concerned.

Another sponsor of the ordinance, Oliver Thomas, represents the Blackest of New Orleans’s five council districts. In an earlier stint on the council, Thomas—six months after Hurricane Katrina, and in response to complaints about the fact that displaced poor people were not being helped to return to the city—asserted that government agencies and programs had “pampered” the Black poor and then infamously declared, “We don’t need soap-opera watchers now.” By 2022, Thomas had thrown himself into the fight against the homeless scourge in a hands-on way, personally rousting “vagrants” from an intersection in his district and proudly tweeting a video of his activities. Perhaps conveniently, the homeless people that he accosts in the predominantly Black neighborhood are white. As he objects repeatedly to their presence on “public property,” one of them asks, “We’re not the public?”

The answer from Thomas and his cosponsors—and from an alarming number of others around the country, both in government and not—is a resounding “No!” This demonization of homeless people is textbook scapegoating politics. We’ve seen it many times before, directed at other populations, and each time they’re presented as posing a uniquely perilous threat—so no lessons are ever learned. As reprehensible as this assault on the most vulnerable people in our society is, what’s even more disturbing is that it’s now part of a campaign by Trumpists and other reactionary elements to create an appearance of chaos in society, setting the stage for the intended imposition of authoritarian rule and the elimination of all the social protections we’ve won in the past century. Our only hope for avoiding that nightmarish outcome is to expose this for what it is—a right-wing capitalist-class plot—and try to organize among the broad mass of working people to counter it.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply-reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish everyday at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation