June 12, 2024

At least they’re giving themselves a fighting chance.

At least they’re giving themselves a fighting chance. On late Monday evening, the leaders of France’s four principal left-wing parties—France Insoumise (“Rebellious France”), the Socialist Party, the Communists, and the Greens—announced the formation of a “new popular front” for the snap parliamentary elections that will be pivotal for the future of the country. Just 24 hours earlier, President Emmanuel Macron dissolved the National Assembly, calling people back to the voting booths on June 30 and July 7 to renew the lower house of France’s legislature and lay the groundwork for a new government.

The widely unexpected dissolution was announced on television a mere minutes after Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally won an historic victory in the June 9 elections for the European Parliament in Strasbourg. It ends the tumultuous history of the divided legislature elected in 2022 and seems primed to benefit the far right, which could ride the momentum of its latest victory into its first experience in government. Jordan Bardella, the National Rally’s official president and its lead candidate for Sunday’s EU vote, won a walloping 31.4 percent, more than double the 14.6 percent won by the Macronist runner-up Valérie Hayer. With Le Pen in charge from the sidelines—in waiting for the 2027 presidential elections—the 28-year-old Bardella is the likely figure to seek appointment as prime minister should the National Rally secure a working majority in a few weeks time.

The imminent possibility of a far-right government was the impetus needed to whip France’s left-wing forces into unity. Citing the “historic situation” facing the country in a press release issued late Monday evening, the parties are calling for an alliance bringing together all “left-wing and humanist forces.” As party leaders gathered at the headquarters of the Greens to hash out the framework of an alliance, thousands of protesters massed a few hundred meters away on Paris’s Place de la République, demanding unity and singing anti-fascist slogans and chants

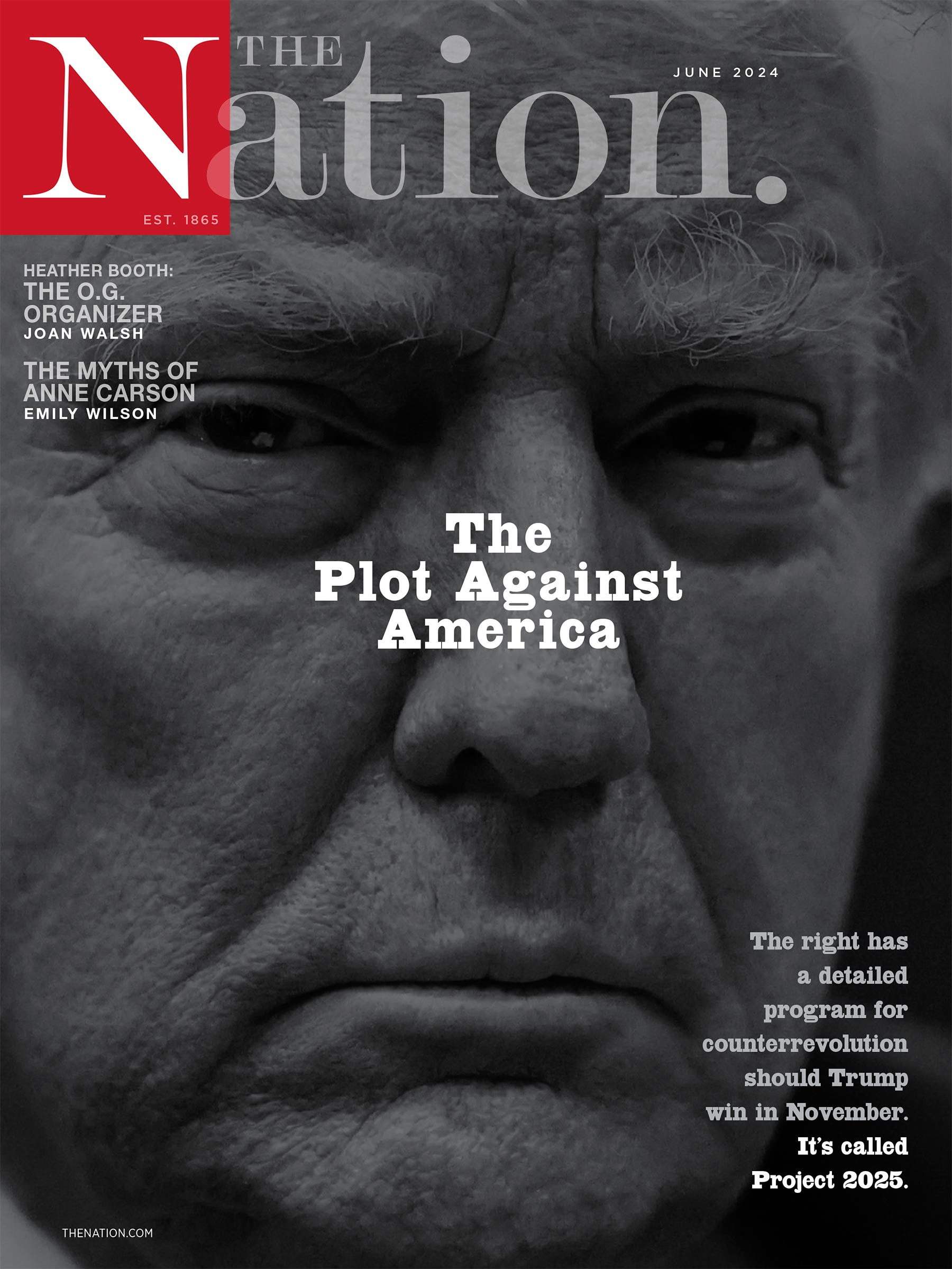

Current Issue

The details of the pact will emerge in the coming days, including a resolution to the thorny issue of who will stand as the left’s proposed prime minister. For now, the alliance means that the parties will rally behind common candidates across all 577 legislative districts in the June 30 first-round vote. Such an agreement is instrumental for ensuring that as many left-wing and progressive candidates as possible qualify for a run-off vote to be held on July 7. On Wednesday afternoon, negotiators announced that a districting agreement had been reached, according 279 candidacies for France Insoumise, 175 for the Socialists, 92 for the Greens, and 50 for the Communists.

The front’s combined candidates will also run on what the unity agreement calls a governing “program for a social and ecological rupture in order to construct an alternative to Emmanuel Macron and combat the racism of the far right.” This will likely include pledges to reverse Macron’s unpopular 2023 retirement reform, the repeal of Macron-era laws designed to restrict civil liberties, the abrogation of a restrictive immigration law passed this winter (with the support of the National Rally), and increases in the minimum wage.

The left-wing alliance marks a last-ditch revival of the New Ecological and Social Popular Union formed in the lead-up to the 2022 parliamentary elections, which secured 151 left-wing seats in the National Assembly and was instrumental in denying Macron an absolute majority. The NUPES program was largely based on the propositions of veteran leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Insoumise. But the alliance finally succumbed to infighting in late 2023, as divisions boiled over concerning the European Union, the war in Ukraine, the genocide in Gaza, and spurious accusations of antisemitism targeting France Insoumise, by far the largest of the four parties in the now-dissolved National Assembly.

Before this month’s European elections, France’s left-wing establishment, specifically the old elite in the Socialist Party (PS), spurned calls for an alliance in the hope that it would allow it to reimpose control over the left and marginalize the Mélenchonist wing. The leader of the PS’s European campaign, Raphaël Glucksmann, came in third in the June 9 vote, often employing staunchly anti-Mélenchon rhetoric. Since Sunday, thankfully, he and the Socialist right appear to have been contained by the more unity-minded wing of the party.

Buyer’s Remorse?

Arevived left-wing alliance is one of many surprising shifts provoked by Macron’s decision to hurl the country into an early-summer political crisis. As the idea for dissolution was hatched in the weeks before the June 9 election, the president and his closest advisers banked on the probability that oppositions on the center-left and the center-right would remain split from their more radical wings, allowing Macronists to evoke the traditional “republican front” in the event of a runoff. In the best of all possible worlds, these divisions, coupled with the two-round voting system used in national elections, would leave a narrow path for an embattled presidential coalition to restore a modicum of governing legitimacy. And in the worst of all possible worlds, according to the most cynical reading of the president’s motives for dissolution, a few years of chaotic far-right government would disenchant voters with the Le Pen brand.

That’s a lot of “woulds.” Even by this president’s standards, dissolution was a brash move—the political equivalent of hurling an elephant into a porcelain shop. Key members of the president’s party, including his prime minister, Gabriel Attal, and the president of the National Assembly, Yaël Braun-Pivet, were blindsided by a decision made within a restricted inner circle. Even Macron’s European partners are said to be up in arms over the French president’s latest gambit, which opens the way for a protracted period of instability—to say nothing of a possible far-right government—in a pillar of the European Union. “Everyone is trying to save their skin,” says outgoing Macronist MP Christopher Weiss of the mood in the party, little under a month before Paris hosts the 2024 Olympics.

As the left finalizes the terms of its alliance, another obstacle to the president’s plan emerged on Tuesday: A wing of the old conservative establishment appeared to be moving toward an alliance with the National Rally. In a major shift, Eric Ciotti, president of the center-right Républicains (LR) announced yesterday that he would seek a pact with the National Rally. Ciotti’s move was just as soon lambasted as a treacherous betrayal by leading figures among the Républicains—namely, mayors, senators, and regional presidents not facing reelection—in what rapidly devolved into an intraparty war. The details of that “deal” were unclear, but Bardella said on Tuesday evening that “dozens” of LR candidates could be spared from confronting a National Rally competitor if they agreed to work together once in power. In one apparent concession—and a wink to the financial markets—Bardella has announced that a potential hard-right government would not seek to unwind Macron’s retirement reform forced through the National Assembly by decree thanks to the tacit support of the Républicains. By Wednesday evening, after Ciotti quite literally barricaded himself in the LR headquarters, the party’s brass announced that the rogue leader had been formally expelled.

In the face of a growing fiasco, Macron and his allies are still trying to project an air of confidence. Yet the president’s long-winded press conference on June 11 sounded less like a self-assured campaign launch than a last-ditch plea for a vacillating centrist offering that many French voters and politicians seem committed to bury. Again peddling the pernicious lie that Mélenchon and France Insoumise are a threat on par with Le Pen, Macron called on Glucksmann supporters or conservatives dismayed by Ciotti to rally to the center. He’s spinning this forced election as a salutary chance for “clarification,” one that throws down the gauntlet for a decisive battle between the “extremes” (always in the plural) and the republican forces (himself). But a critical mass of people just don’t seem to buy it any more.

A Long War

If it survives the coming negotiations, there’s no way around the fact that France’s left-wing alliance faces a steep uphill battle. Had the left combined forces in the European elections, it would have edged out the National Rally by a few decimal points, assuming that the parties’ respective voters supported the unity ticket. Yet the National Rally can also claim a reservoir of additional voters, namely from other formations on the right. The hope of an electoral alliance on the left is that it can provide a much-needed boon of electability and enthusiasm, bringing in abstentionists by piercing the illusion—carefully constructed since 2017—that the only choice before French voters is between Macron and the National Rally.

What polling exists must be taken lightly, but it paints a picture of the coming fight as difficult. One June 11 poll predicts that 35 percent of first-round voters will support the National Rally—with another 13 percent supporting other right-wing forces. In the event of a divided left-wing ticket, Macron’s coalition is in a far-off second at 16 percent. If the left unites, the left will snatch the second-place spot thanks to the support of 25 percent of first-round voters. The far right was evidently the most prepared force for these snap elections: It had a sealed and ready “Matignon Plan”—a reference to the name of the prime minister’s sumptuous Parisian palace. Le Monde is reporting that the polling studies consulted by the presidential cell that concocted the dissolution plan showed that the National Rally would win between 250 and 300 seats in the event of snap elections—a boom from the 88 seats the party holds in the ousted National Assembly. It takes 289 seats to hold an absolute majority.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

What this makes abundantly clear is that there’s very little time to finalize a coherent program and rally behind a candidate for prime minister, one who can make the case for “rupture” while appealing beyond the left’s usual base. For France Insoumise loyalists, that means a figure from their top leadership, ideally Mélenchon. This is likely a nonstarter for the leadership of each of the other left-wing parties, however. While the left’s actual party leaders were doing the difficult work of coalition building on Monday evening, the ever-presumptuous Glucksmann took to television to lay out his five conditions for unity. As a possible PM candidate, he suggested Laurent Berger, former leader of the center-left CFDT union—who probably would prove too cautious a choice for the France Insoumise apparatus and its supporters. An LFI deputy on the party’s more moderate wing, François Ruffin, was the first to call for a “popular front” on Sunday night and appears to others, including some in the Socialist Party, as a natural unity candidate.

If the “popular front” holds, the next few weeks are also going to need a truly massive groundswell of organizing. One France Insoumise activist in Paris’s 19th arrondissement said the party was “drowning” in sign-ups, as a torrent of people reached out to join campaign organizing in just the last 72 hours. But if France’s left has any hope of turning the tide, that energy is going to need to extend beyond the traditional centers of left-wing power—major cities, like Paris, Marseille, Lyon, and Lille and their surrounding suburbs—and into the rural districts where Le Pen has made such decisive inroads in recent years. Le Monde’s map of the European results shows France drowning in the dark brown of fascism, as the National Rally soared to first place in almost all electoral districts beyond the urban hubs.

Three weeks is barely a skirmish. What the left really needs is the time for a long war, one that can unwind the painstaking normalization of the far right as a credible solution to France’s problems. Macron has twisted the Fifth Republic to its limits and opened a wide door for the National Rally. It’s probably their election to lose.

Dear reader,

I hope you enjoyed the article you just read. It’s just one of the many deeply-reported and boundary-pushing stories we publish everyday at The Nation. In a time of continued erosion of our fundamental rights and urgent global struggles for peace, independent journalism is now more vital than ever.

As a Nation reader, you are likely an engaged progressive who is passionate about bold ideas. I know I can count on you to help sustain our mission-driven journalism.

This month, we’re kicking off an ambitious Summer Fundraising Campaign with the goal of raising $15,000. With your support, we can continue to produce the hard-hitting journalism you rely on to cut through the noise of conservative, corporate media. Please, donate today.

A better world is out there—and we need your support to reach it.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

If we’re set on Armageddon, America’s existing force of nuclear submarines is more than enough.

William Astore

Global courts challenge Israeli action in Gaza.

Reed Brody

Demonizing China allows Republicans to unite around an authoritarian agenda at home—and provides a convenient rationale for unfettered Pentagon profiteering.

Feature

/

Jake Werner