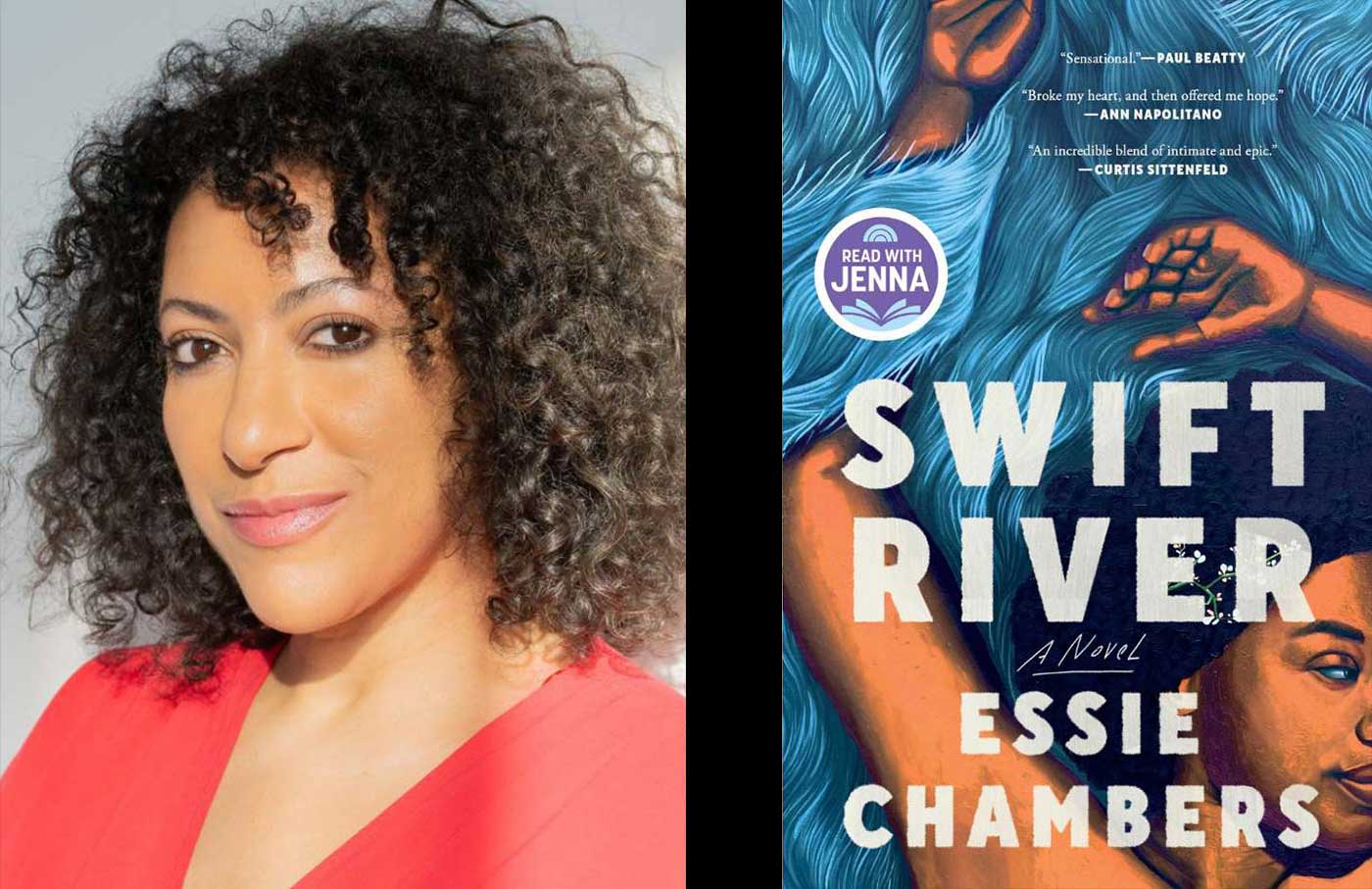

Early on in the pages of Swift River, the astonishing debut novel from author Essie Chambers, teenage protagonist Diamond Newberry describes a typical scene as she walks down Main Street in the book’s titular New England town:

If I’m on foot, people stare so hard it’s like I’m on fire. Heads in cars flip all the way around. Workers in shop windows stop what they’re doing to look at me blank faced—as if I’m not their daughter’s classmate, their friend’s co-worker, like they haven’t known me my whole life.

“When I forget the spectacle of myself,” Diamond wryly notes, “I look behind me to see who is the me.”

Diamond is 16, biracial, overweight and seemingly in the midst of outgrowing everything familiar—her body, stretch-marked with the weight of racial trauma; her relationship with her loving but grief-numbed mother, Anna; and perhaps most of all, her down-at-the-heels, otherwise all-white hometown, where Diamond’s size, skin, and story mark her as a permanent outsider. It is the summer of 1987, seven years after her African American father abruptly and mysteriously vanished, and with him, Diamond’s only connection to an extended family whose Blackness reflects her own. Like the figure of “Pop,” Blackness is like a specter in Diamond’s life, intangible yet omnipresent in its echoing and mystifying absence.

Swift River is “a story about leaving,” Diamond indicates from the novel’s outset, and her desire to get out is indicated by bedroom walls adorned not with images of pop stars or 1980s teen idols, but aspirational destination photos: the pyramids, California’s redwood coast, Stonehenge. There are also driving lessons, kept secret from her mother, whose unaddressed mourning manifests as codependency with her daughter. Despite, or perhaps because of, all she has endured, Diamond possesses emotional insights beyond her years—and a wit sharpened by the coarseness of fatphobic insults and racial slights. In one scene, she discovers the word “NIGER” has been scrawled next to her family’s listing in a public phonebook. Grabbing a pen from her purse, she quickly, cheekily adds a final bit: “—The third longest river in Africa!”

At its heart, Swift River is about the shedding of secrets—personal, familial, and communal—and concealed truths that Diamond learns have resulted in a transgenerational sense of placelessness, stagnation, and loss. That process begins when Diamond unexpectedly receives a letter from Auntie Lena, a previously unknown paternal relative. Thus begins an exchange that unearths the hidden history of Swift River’s once-thriving Black community, a population driven from the town’s borders by racist Jim Crow violence, upending Diamond’s Black family tree at the roots. In that history, she finds not just a kindredness with bygone ancestors but also the familial legacy that blossomed from so many fractured branches. It’s both recognition and reckoning, helping Diamond to locate herself in her past, make sense of her identity in the present, and map the route that lays out her future.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In Swift River, Chambers illuminates how the sprawling, twisted branches of our family trees traverse both genealogy and time—tracing not just ancestral lineages but history writ large. Diamond’s family narrative is inextricably tangled in a larger history of race and place in America. The expulsion of entire Black communities from towns like Swift River was not uncommon during the Jim Crow era, a period marked by anti-Black pogroms and white vigilante violence. Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Florida, were all-Black towns leveled by white terror violence, finally acknowledged only in recent years, but there were many more. Equally common were towns like Swift River—all-white “sundown towns” where Black people were banned after dark, and faced potentially lethal consequences if they lingered after sunset. According to James Loewen, author of Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, some 10,000 sundown towns existed in America well into the 1960s. Chambers says that upon beginning research for Swift River several years ago, she discovered a little-known geographic aspect of sundown towns.

“I thought I understood what sundown towns were. I had read about them. We’ve all seen them represented in movies, we know the role the Green Book played because of sundown towns,” Chambers told me. “But what I didn’t understand, that [Loewen’s] book helped me to realize, is that sundown towns were primarily a northern thing—North meaning Midwest and West as well—and formed part of the response to the Great Migration. That’s when I started to think about what it would mean for the book if Swift River were a former sundown town.”

Author Essie Chambers, it cannot be stated enough, is not Diamond Newberry; likewise, Swift River is not an autobiography. (Authors of color who write characters of color are all too often assumed to be unimaginatively recounting their own lives.) But like Diamond, Chambers is biracial (Black-identifying), and grew up in a small New England town where she, her siblings, and her father were among the few residents of color. There are as many Black American family stories as there are Black American families, and the details differ in critical ways. But for most Americans of color, there is relatability and resonance in stories of navigating inhospitable white spaces, just as there is in the experience of being the only one.

“When you have to maintain your sense of self, when you have to understand your identity in the absence of Black culture—that, too, is a part of the Black American experience,” Chambers told me. “And I’ve now experienced it in so many different contexts. There’s the experience of being born into that situation, and that has its own set of rules. There’s the corporate experience of it, where you are often folding yourself in half.”

Those insults can hollow out and diminish, but just as frequently, they can also accrue and amass within us. Chambers noted to me that Diamond’s weight, in part, results from having to swallow so many racial microaggressions without response. Most painfully, for Diamond, those come from friends, family members and loved ones whose words inadvertently reveal their own unexamined anti-Blackness. In Swift River, Diamond’s white maternal grandmother fails to notice that a tchotchke she brings home is a racist caricature; Diamond’s one friend, while earnestly trying to protect her from a bigoted stranger hurling racist slurs at her, offers up a tokenizing defense, telling the stranger that Diamond is “not like that.” Chambers says her deftness in depicting those quotidian brushes with anti-Black racism were influenced by Claudia Rankine’s book of poetry about encounters with anti-Black racism Citizen: An American Lyric.

“There was something about the way that [Rankine] expressed microaggressions, which was that she showed they so often came from people she loved. I hadn’t been thinking about it that way, and that shifted my thinking,” Chambers told me. “Swift River wouldn’t work if all the white characters were just cartoonishly bad. That wasn’t my experience when I was growing up. Yes, maybe if I went for a walk, someone might scream something ugly out of a window. But that wasn’t the daily experience of being there. It was much more about having to stay in your body somehow—in your skin—as people you cared about—teachers and friends—said hurtful things, maybe without even understanding that they were hurtful, just to be able to survive that environment and feel like a part of it.”

And perhaps to feel, however fleetingly or superficially, safe. Swift River is the only home Diamond has ever had. Known dangers can seem less threatening than unknown dangers. Diamond’s resolve to leave Swift River flags during the moments when she thinks, “These are my people in so many ways,” as Chambers puts it. “At least, until she finds new people.”

In the slowly deteriorating familial home Diamond shares with her Irish American mother, there is a bounty of family heirlooms: “feathery yellowed papers announcing ancient births and deaths and marriages, antique wedding chests, lacy baptism dresses,” allowing Diamond to feel like she’s “frolicking with the ancestors.” Contrast her mother’s tangible family tree roots with the rootlessness of her gardening-obsessed father, who to Diamond seems “as if he sprang from the ground like one of his plants.”

“I’ve always felt the gaps in my family tree,” Chambers, who can trace her mother’s side to an ancient King of Scotland, says. “Especially because I’ve had these riches on my mother’s side, I saw how they helped form her identity and her sense of herself.”

This is a typical African American conundrum, the result of a lack of documentation from the dislocating force of slavery, and a disregard for the humanity and personhood of Black enslaved peoples. But in writing Swift River and as a producer on the highly decorated 2022 film Descendant—director Margaret Brown’s documentary about the last known ship to traffick African people into enslavement in the United States, and the living descendants of those onboard—Chambers learned how legacies are passed in so many other ways.

“Someone asked me recently how I learned storytelling, and I realized a lot of it was from watching my father and his brothers tell family stories on the porch,” Chambers told me. “That was the thing I learned working on Descendant. Oral history is not a lesser history, especially for people who are not part of the dominant culture. It’s essential to tell the stories and pass them down in that way. And so I was part of many of those moments—the passing down of history, without even understanding that was happening. So in that way, I have a very different understanding of history on my dad’s side. But it’s one that is also very rich.”