A new Hulu docuseries about Black Twitter wants to be a tribute piece to Black millennial intellectual and creative output. But what it becomes is something else entirely.

What I remember from the night of the grand jury’s decision not to prosecute the police officer who murdered Mike Brown Jr.: The sound of Brown’s stepfather’s voice screaming “BURN THIS BITCH DOWN!” breaking through a rowdy, restless crowd in Ferguson, Missouri, as Brown’s mother oscillated between a muffled cry and a boundless wail. I was hundreds of miles away from the heat of bodies packed against one another, exchanging sweat and nervous energy. I don’t know if I was crying or if my body had simply exhaled from holding itself in for so many months.

August of this year marks a decade since Brown was killed by a Ferguson police officer. That singular event feels formative in a way that’s difficult to overstate. The world feels bifurcated by a time before the murder of Mike Brown Jr. and life after his murder. I was in North Carolina and had just turned 19 the day after Brown’s death, as news was beginning to trickle in slowly about what had happened. I resided primarily on Tumblr at the time, where screenshots of tweets from people who were on the ground in Ferguson became an essential part of online mobilization.

“We saw what was taking place in Ferguson, through Twitter,” said journalist Brandon “Jinx” Jenkins in Black Twitter: A People’s History, a three-part docuseries now streaming on Hulu. “Twitter was captioning life live. The news was not.

”

Not unlike Jenkins and most other people who stayed tuned in to what was really going on in this unassuming city in Missouri, I received my news not from corporate media but from social media sources like Twitter, now X. It became common to see tweets from people like journalist Wesley Lowery and organizer Johnetta Elzie reporting what was going on in Ferguson. “All I had was my Twitter and my Facebook,” Elzie said in archival New York Times footage featured in the docuseries. “I felt someone somewhere would really care about what I was saying.”

In Black Twitter, director Prentice Penny (showrunner of HBO’s Insecure) gathers a who’s who of Black Internet personalities to discuss the formation of the online community of Black users on then-Twitter. The docuseries is an adaptation expounding on the three-part oral history of the same name written by Wired’s Jason Parham and published in 2021.

“It’s the cookout. It’s the Soul Train line,” Parham says in the docuseries. “Black Twitter is us.”

Current Issue

In the docuseries, panelists talk about how the murder of Brown and the protests that followed are credited as what legitimized Black Twitter as a political force. “The Black Lives Matter movement is the defining civil rights movement of our time,” Parham says. “And it would’ve been impossible without Black Twitter.”

Despite this, discussion of Ferguson only takes up about five minutes of the docuseries’ nearly three-hour runtime. The recollections that were shared didn’t transport me back to witnessing the uprisings and violent responses to the protesters through my phone screen. Instead, I felt drawn toward a possibly more horrific present-day reality. The years since the non-indictment of the cop who killed Mike Brown Jr. have brought us even more names of Black people who were murdered by the state while their murderers got off without being held accountable for their actions. In the 10 years since Brown’s murder, police budgets also have continued to balloon.

It’s this reason why it became increasingly difficult, as the docuseries went on, for me to listen to earnest pontification about the “power” of Black Twitter. This thesis collapses against the weight of reality.

What Black Twitter unwittingly unveils, however, is how a handful of “thought leaders” and “change makers” became empowered through Twitter to be a “voice” for the collective and make it seem as if the system is acquiescing to the demands of the people. In reality, this “people’s history” conflates visibility with authority and confuses liberation with Black American people’s production of online cultural critiques and banter.

The docuseries opens with a montage showing people from news anchors to comedians to actors saying “Black Twitter” to demonstrate the cultural impact and visibility of this online community. Impact is emphasized again when Penny discusses the uptick in diverse representation taking place across the media ecosystem during the early to mid 2010s, as Black Twitter gained in prominence. “A lot of brands did jump on the representation bandwagon because they believed it was the right thing to do,” Penny says. “Some changed because they didn’t want to be canceled. Some changed to make money.”

Much has changed since then, with conservative justices on the Supreme Court gutting civil rights–era protections against racism in education and the voting system and conservatives launching deeply funded attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. It is negligent on the part of the documentarians not to further interrogate why brands that initially involved themselves with Black movements have since abandoned them.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

After all, it was during the surge in inclusivity in the 2010s when we began seeing the corporate co-option of the Black Lives Matter movement. In the Wired article, Lowery refers to “a commodification of Blackness.” However, it was not merely just Blackness that was being treated like a commodity, but Black radicalism specifically.

Companies like Wells Fargo sponsored a panel with Deray Mckesson, an activist who rose to prominence for Twitter reporting of Ferguson. Nike famously partnered with Colin Kaepernick after the former football player was blackballed for his take a knee protest. Cadillac featured activist Tamika Mallory in one of its commerciaals.

While some activists and some of the most powerful Black Twitter voices gained these opportunities, most everyone else found themselves in the same place, or even worse off, over the years. April Reign, who is highlighted in the docuseries for her #OscarSoWhite campaign that she started in 2015, puts it this way in the Wired article: “There’s so many examples of how Black Twitter has been undermonetized for years. And yet others have been able to make entire careers off of our brilliance.”

There’s this persistent underlying suggestion made throughout the docuseries that Black Twitter had the upper hand in how corporations operated. “It felt like the promise of Obama’s hopeful America was really about to happen.” Penny says. “And Black Twitter was at the helm of it.” It only becomes clearer in the years that have since followed that not only did they not have the upper hand; they had at best a pinkie-finger level of involvement.

It took some years for many of us to understand that what is often touted as diversity is actually a neutralizing tactic—and that DEI is not an appropriate or legitimate response to the state violence inflicted upon Black people. But it became a legitimate way for a handful of people to find career opportunities. It can be understood that capitalism stymies our ability to make only ethical choices, while still refusing to allow our movements to become entangled with corporate interests.

Black Twitter wants to be a monument, a tribute piece to Black millennial intellectual and creative output. But what it becomes instead is an artifact of an era of the Black idealist ensnared by pursuits of power and legitimacy under white supremacy.

The docuseries panelists are asked to describe Black Twitter in one word. Among the many words that were said, “community” was repeated twice.

In reality, however, Black Twitter was never the communal space that many purport it to be. In a country with diminishing third places, Black Twitter became the barbershop, the salon, the church, the corner store, the quad, and whatever we needed it to be to fill the gap in connection that this increasingly lonely world was creating. Unlike those spaces that were once the mainstays in Black American life, there’s a distance—proverbially and literally—that prohibits real connection.

In February of this year, feminist and Twitter activist Shafiqah Hudson died after suffering from long Covid and cancer. One of the more jarring moments while watching the docuseries is getting to the end of the section where they were talking about the ubiquity of Russian bots during the Trump administration, without any mention of Hudson’s foundational work with #YourSlipIsShowing. Hudson created the hashtag in 2014 after noticing puppet accounts that were pantomiming Black users in an attempt to create hostility toward Black feminists on the platform. One of her last tweets on her account was an unfulfilled GoFundMe to help with her medical bills.

If this docuseries is a “people’s history,” it also raises the question: Which people exactly?

In the final episode of Black Twitter, panelists mull over the future of the platform since billionaire Elon Musk’s acquisition of the site. Should we make a great digital migration to other Twitter copycats, some wonder? Should we stay and continue to let our presence be known? “You may ‘own it,’ technically, cause you paid for it, but it’s ours,” says journalist Jemele Hill.

But it’s not ours. It never was. Digital displacement mirrors on a smaller scale the physical displacement that has wreaked havoc within our communities for decades. Not even Black Internet gathering spaces could be spared from the violence of the colonial reflex to silence and destroy attempts at Black communion.

Black Twitter wanted to be a homecoming but ultimately found itself being a homegoing.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that moves the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories to readers like you.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

The money-saving measure happening in districts throughout the country leaves too many kids without anything to do—or in some cases, anything to eat.

Left Coast

/

Sasha Abramsky

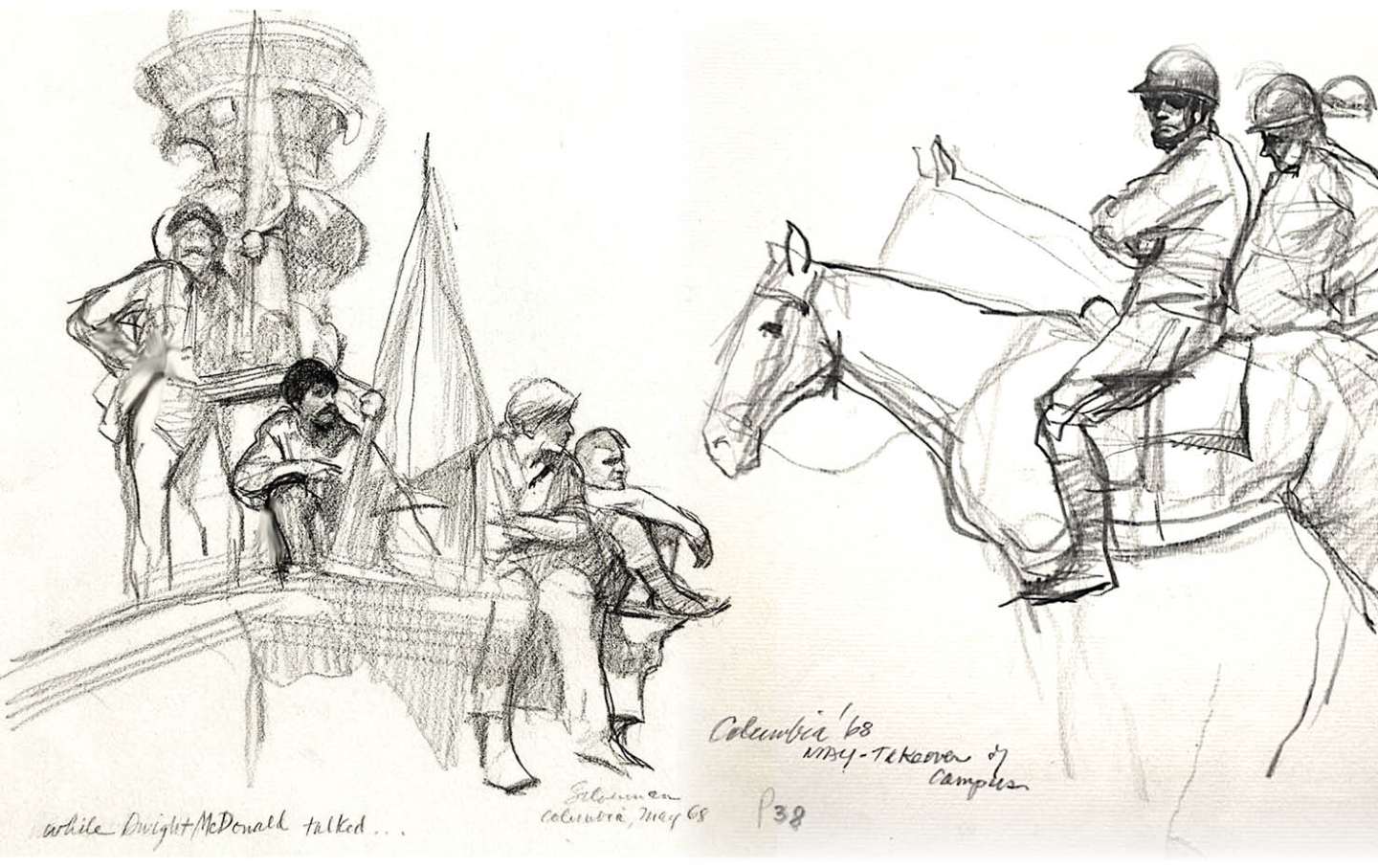

I sketched the student protests at Columbia University nearly 60 years ago. Here is what I saw.

OppArt

/

Burton Silverman

In a topsy-turvy ruling, the conservatives on the Supreme Court ordered Louisiana to use a VRA-compliant congressional map while the liberals dissented.

Elie Mystal